Dear Friends,

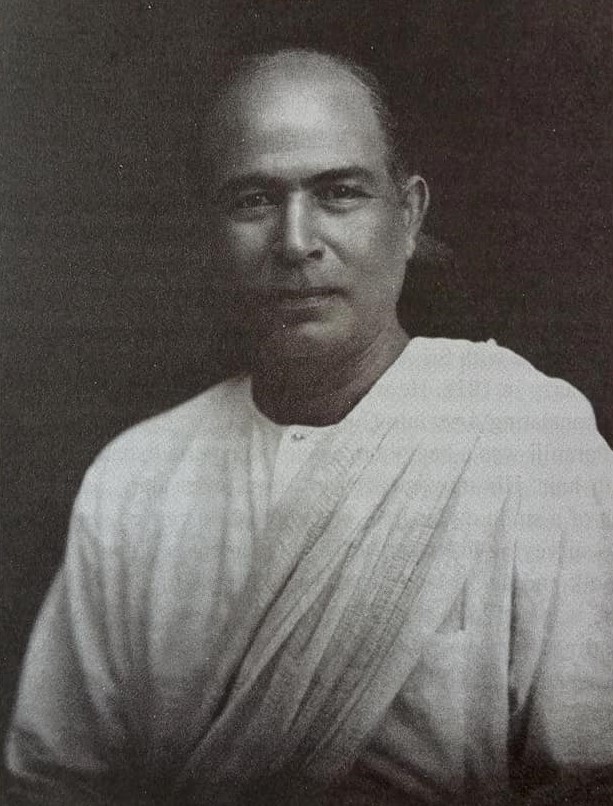

Ambalal Balkrishna Purani (26.5.1894—11.12.1965) was a Gujarati revolutionary who met Sri Aurobindo in 1907. A graduate from St. Xavier’s College (Mumbai) with Honours in Physics and Chemistry, he established a chain of gymnasiums in various parts of Gujarat. He went to Pondicherry in December 1918 to meet Sri Aurobindo who assured him that India’s freedom was imminent. He visited Pondicherry again in 1921 and joined Sri Aurobindo’s household as an inmate in 1923. Posterity would always remain grateful to him for keeping detailed notes of the ‘Evening Talks’ Sri Aurobindo had with His disciples. His duties in the Ashram included answering correspondence arriving from Gujarat, preparing hot water for the Mother’s bath at 2 a.m. and meeting aspirants who were keen to know about the Integral Yoga. He became Sri Aurobindo’s personal attendant when the latter met with an accident in November 1938. After Sri Aurobindo’s mahasamadhi, he took some classes in the Ashram School. He visited U.S.A., U.K., Africa and Japan to preach the message of Sri Aurobindo. A prolific writer who wrote in English and Gujarati, his published works include Evening Talks with Sri Aurobindo, The Life of Sri Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo in England, Savitri: An Approach and a Study, On Art: Addresses and Writings, Sri Aurobindo: Addresses on His Life and Teachings, Sri Aurobindo’s Vedic Glossary, Sri Aurobindo’s Life Divine, Studies in Vedic Interpretation, Sri Aurobindo: Some Aspects of His Vision and Lectures on Savitri.

In 1955 Purani visited England to participate in the Colloquium at Oxford on Contemporary British Philosophy and to gather whatever material was available of Sri Aurobindo’s life in England from 1879 to 1893.

We are happy to publish in the website of Overman Foundation the diary of A.B. Purani which chronicles his sojourn in England. The diary has been published in two parts. Here is the first part of his diary.

With warm regards,

Anurag Banerjee

Founder,

Overman Foundation.

___________

A.B. Purani’s England Diary

I went to England in August 1955. But the decision to go was taken almost at the end of July. There had been correspondence before with the British Council which had invited me to participate in the Colloquium at Oxford on Contemporary British Philosophy. I replied to the representative, who was known to the Ashram, asking for two occasions to represent dynamic Indian thought, each exposition to be of 20-25 minutes’ duration. Altogether there were going to be about 26 such talks. The reply was not encouraging; still I sent it to the Mother to know if she would want that I should accept the offer. She did not approve, and I wrote to the British Council at Oxford pleading my inability to attend. Then the Director wrote a letter pressing me to accept the invitation as he would try his best to help me in making contacts, though the committee that arranged the programme might not want an exposition of thought other than that of the Oxford school.

I sent the letter to the Mother. She suggested I could accept the invitation. I did; but it was nearly the end of July; and getting a passport and booking a berth in a steamer had all to be done. Money for the voyage had also to be obtained. I left Pondicherry in the beginning of August and there was much uncertainty in the minds of many Ashram friends about getting accommodation in the steamer from Bombay as reservations usually are done months in advance. But I felt that things would some-how get arranged. And place was found for me, on the 12th of August, in the S. S. Carthage.

The first days at sea were stormy and it was raining heavily. Even some of the crew were sea-sick. The passengers naturally were worse. I recovered after two or three days. The name ‘Carthage’ had reminded me of the steamer by which Sri Aurobindo had returned to India in 1893. After Aden I went to the Captain and asked him whether we were on the same boat that had voyaged to India in 1893. He brought out the log-book and showed me that the old Carthage had been recast in 1926, but fundamentally it was the same Carthage. I was much moved when I knew that I was going to England to work for Sri Aurobindo and the Mother by this boat. Such coincidences have occurred more than once.

When I accepted the offer to go to England I had a threefold idea of the work. to be done : 1. To convey to the English people some idea of Sri Aurobindo’s life and work. 2. To awaken interest in his intellectual and cultural contribution at the Universities and among the intellectuals. 3. To gather whatever material was available of Sri Aurobindo’s life in England from 1879 to 1893. In fact I undertook the voyage in the spirit of a pilgrim; because Sri Aurobindo had lived for 14 years in England it was a place of pilgrimage for me. Generally people undertake such journeys for a change, for enjoyment or for studies or for commerce. None of these was my motive. I was conscious that I was undertaking a responsible task alone in a foreign country at three score years. From packing suitcases to preparing programmes and reserving seats, everything had to be done by myself with the load of responsibility weighing on me.

After Aden I had no sea-sickness and was in fair condition when I reached England. Letters of introduction to the India Office were there, but when I saw the working of the India Office in London I gave up the idea of using them. It lacked regularity, organisation, cleanliness, efficiency and a living sense among the workers that they represented “free India”. The British Council gave me all possible help it could, I must note with gratitude.

The most discouraging discovery was to find that only a few in England knew about Sri Aurobindo and his contribution to English literature and language.

The work in England started on 30th August, and lasted upto 2nd December 1955 — a period of three months and three days.

The following is the list of meetings addressed :

- 4.9.1955: At the Study Circle; 31 Queens Gate Terrace, S.W.7.

- 6.9.1955: Y.M.C.A. London; 41 Fitzroi Square, W.1.

- 11.9.1955: Hindu Association of Europe; 35 Polygone Square, Euston.

- 2.10.1955: Indian Association; Leeds University.

- 17.10.1955: Small group at Philip Bagby’s place; Beaumont Road, Oxford.

- 21.10.1955: Indian Institute of Culture; 62 Queens Gardens, W.2., London.

- 22.10.1955: Gujrati Mandal; 35 Polygone Square, Euston.

- 23.10.1955: At the Study Circle; 31 Queens Gate Terrace, S.W.7.

- 28.10.1955: The Royal Indian Pakistan & Ceylon Society, Ulster room, Overseas House, Park Place, St. James St. S.W.1, London.

- 9.11.1955: B.B.C. Office; Broadcasting House, Picadilly.

- 20.11.1955: Study Circle; 21 Queens Gate Terrace, S.W.7.

- 20.11.1955 (Evening): Spiritual Circle of Miss Alison Bernard; 4 Wimple Mews W.1.

- 25.11.1955: Cambridge Group;Friends Hall, Cambridge.

- 1.12.1955: Ramakrishna Mission, London.

I interviewed 80 to 90 intellectuals during the period and was at Cambridge, Oxford, Leeds and Durham Universities and had the pleasure of offering Sri Aurobindo’s photograph — and a set of his books to be kept at Cambridge and Leeds Universities. The broadcast from B.B.C. was on the air on 19.12.1955. I had, incidentally, met many professors of philosophy at the Oxford Colloquium and at other Universities, and conveyed to them information about Sri Aurobindo.

The information about Sri Aurobindo’s stay in England was gathered from diverse and even apparently accidental sources. For instance, the information about the various houses occupied by him was found from letters of his brother Monomohan to Laurence Binyon. I knew of the fact of correspondence between them and also about Binyon’s letters to Monomohan given to the Calcutta University and lost during the period of the Japanese aggression. Finding out Mrs. Binyon’s address I wrote to her asking if there were letters of Monomohan to Binyon. I had a faint hope that they might throw some light on Sri Aurobindo’s life in England. She replied after two months and sent me the letters which furnished four addresses of the houses in London and also information about the places they had visited in England. The confirmation about the identity of the houses was obtained from the London County Council.

On 30th August 1955 the Carthage disembarked at Tilbury in the afternoon and I reached 23 Pembridge Villas in the evening, a home for Vegetarians.

On 31st August 1955 I got an appointment with the British Council. I was totally ignorant of the address of the Council! Mrs. Vivian Morton sent a phone-call welcoming me and so did Miss Doris Tomlinson, who said she was free only between seven and eight in the evening, as she was in charge of an organisation which served as a refuge for about 125 old people. Mr. Peter Cromton Chalk, a friend who had been a disciple of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, had stayed here in South Kensington, Queens Gate Terrace, helping Doris in her work. He had come to Pondicherry in 1952 and stayed in the Ashram for about three months. I had written to him from East Africa where I had gone in April 1953, inquiring about the possibility of visiting England for Sri Aurobindo’s work. His reply was very sad and written in a mood of depression as he found such a great apathy in England about higher values of culture. Peter died on November 12, 1953.

The phones that I received on my first day in London gave me the impression of persons who were groaning under a great load of work; all seemed to be working under some invisible whip.

I felt that very day — the first day in England — that from buying stamps from the post-office to finding information about Sri Aurobindo’s life I had to depend only on myself. Nobody was there who could help me. By the grace of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, there was the will to translate resolve into action and my body was strong enough to help me in that.

I must also confess that the situation was like a challenge of the Unknown and this had also its part in awakening the sense of a new adventure for which I felt enthusiastic. At the same time I was not free from a heavy sense of responsibility and even anxiety. It was like swimming in strange waters. So I left the house at 7 o’ clock in the evening with a sort of curious feeling: “Let us see what happens.” At the same time my faith in Sri Aurobindo’s work was unshaken. I walked in London as if I had been familiar with it.

I reached 31 Queens Gate Terrace at about 7-30. Miss Tomlinson, Doris, met me at the gate, and pleaded she had been very busy during the day. I asked her whether Peter had lived here. She said it was true. I said: “I want to visit his room.” She was very happy and led me to the room through a narrow path. I felt his absence as I missed his active help which would have been that of a fellow-disciple. He had known something about Sri Aurobindo’s mission during his visit to Pondicherry. I stood silent for some minutes and then told Doris: “I am going to attempt what Peter wished with all his heart to do. Now I cannot have his help except the inner, but I will not allow that the beginning he has tried to make should fade out.”

I remained in England from August 30 to December 3, 1955. During this period my centre was London from where I used to go to different places.

On the 31st afternoon, I went to the India Office and wanted to use Mr. Kher’s letters of recommendation. But the Commissioner — Mrs. Vijaya Laxmi — was away on the continent. I met Mr. Rozario, in charge of education, who was sympathetic. He phoned to the warden of the Indian Y.M.C.A., Mr. Abraham, and fixed up an appointment on the 6th of September to meet the inmates and guests, and give a talk to them there (Indian Y.M.C.A., 41 Fitzroy Square W.1.)

On 6th September 1955, I reached the place at 6.30p.m. and found there was no notice on the board about the meeting. The warden, Mr. Abraham, was not present. I went down into the cellar and tried to play table-tennis with some boys. The Indian students playing there lacked manners. Those at the billiard table were gambling and quarrelling. It was nearly 6.45. That was the time fixed for the talk.

I went to the telephone girl and told her “Please tell Mr. Abraham when he comes that Mr. Purani whose talk was scheduled to take place at 6.45 came here — as arranged through Mr. Rozario of the India Office — but, finding that Mr. Abraham was absent and no preparations had been made for the meeting, he has gone back.”

Somehow there was a stir in the atmosphere; the telephone girl asked me to wait and within two minutes Mr. Abraham was there making excuses. I had seen him without knowing that he was Abraham — busy with the luggage of an American lady who was going out.

He asked me : “Would you like to see this new building of the Indian Y.M.C.A.?”

I : “I have seen enough of cement and brick. If you had come a little earlier there might have been time for it. But I am interested in living people and the time for the meeting is already past.”

He became a little serious, left me in his office and came back shortly after and begged pardon and after a few minutes he took me to the evening dinner where the talk was to be given. There were about 40 or 45 students; the atmosphere was too light and artificial — nothing in it that was indicative of Indian Culture. My mind sank into depths of sorrow on seeing the condition of an Indian institution in a foreign country — its mismanagement, lifelessness and the slave-mentality of those who had come out here. “These men,” I said to myself, “will go back to India with the holy mark of ‘Europe-returned’! How would they help India in making progress? Their main aim would be to start with a nice pay or get quick promotion on the claim of their being ‘foreign-trained’! Their basic attitude is : Indian Culture is no good; salvation of India lies in imitating Europe.”

I ate nothing that evening. I went from table to table talking to the young people. I found there was no enthusiasm in them for the prospect of meeting a compatriot. I thought: “Nothing external matters; the first thing is to change one’s own inner being. Everything depends upon the change of consciousness.”

The President’ of students was one Mr. Varma studying for post-graduate medicine. Perhaps, they had other kinds of visitors than myself. Many of them might have thought me to be someone who had some axe of his own to grind. At the end Mr. Varma introduced me and said I would tell them something about philosophy. I began: “Mr. Varma wants me to speak to you on philosophy but as you have all taken food it is natural that the circulation of blood moves towards the stomach and it is needed there. I would not like to turn it towards the head. I will briefly tell you one or two things not about philosophy but about life.”

The summary of what I spoke is as follows:

“I never wanted to come to England. You youngmen can hardly realise the emotional upsurge in one like me who had dreamt of Indian independence in his young days. I see before my mental vision the 16th century, adventurous navigators voyaging to India and a relation of commerce being established. It ended in the economic domination and political subjugation of India by England. There was a thin streak of cultural contact also. This cultural contact brought about the renaissance of India culminating in her independence. Thus India owes a deep cultural debt to this little island, — she got so many things from England including the love of freedom. Now that India is free England cannot compel her to do anything. It is now more than ever necessary that India should try to repay the cultural debt to Britain. How can that be done?

“In fact there are two differing standpoints being given to the world today. One is that of Bertrand Russell and his followers who believe in a rational use of the atom-power and an increasing application of scientific discoveries to life as the solution. The other standpoint is that of leaders of thought like Gandhi, Tagore and Sri Aurobindo who in various ways insist on the psychological change in man as the way to solve human problems. Increase in technical knowledge or economic advancement cannot solve the real problem which concerns man’s psychology, for the crux of the difficulty lies in man’s present constitution. So long as man remains what he is, he is bound to invite troubles, difficulties, problems and even disasters. Up to now, the mere outer development has given rise to a universal conflagration; it has not led to unity and harmony. This means higher ethical and spiritual values should be given a greater importance than economic and other values. That need was illustrated during the second world war. It started with a struggle for frontiers and for economic markets and raw materials. But when the war really got into its stride the allies appealed to abstract principles — freedom of speech, of association, and of belief. The Atlantic Charter was declared as embodying their aims.

“Man has to awaken those greater potentialities that are lying dormant in him. As man has sounded the potentialities of Matter, he can equally sound the potentialities of the Spirit. Some may say that it would amount to a belief in something invisible, and even impracticable, because these powers are not seen, are not tangible and therefore not real. Matter alone is real according to them. Equally it is asserted that Spirit is real and holds unlimited powers within it. Man has to become greater than he is; he has to exceed his present self. It is man’s effort to exceed himself that gives him his cultural values and moulds his life in their image.

You, young men, who live in this country, should try to activate in you the effort for inner and outer perfection, to live and embody in your life some element of our spiritual culture. That is the easiest way of repaying the cultural debt we owe to this country. You should remember while you are studying here that you are ambassadors of our culture, you are representatives of it. Is this too high an ideal, is it a tall order? No. One can begin from where he is; everyone has some understanding of what is good and what is bad. One can begin to climb from there and one may find that there is an inner deity in everyone of us which when awakened can lead us higher and higher till we reach the Truth.”

The students and Mr. Abraham were a bit puzzled, probably because they found my address rather out of the ordinary run. Anyhow a good number of them came enthusiastically to see me off at the bus-stand.

*

7th SEPTEMBER 1955 : MEETING WITH MR. C. DAY LEWIS

I had to take a taxi to reach Chatto Windus & Co. Miss Tomlinson indicated the place to the driver. We drove for more than 40 minutes without reaching our destination. Fortunately, I had kept a margin for delay. In London, names of places with ‘Victoria’, ‘Queen’, ‘William’ are so many and so confusing to an outsider that unless one is exact in giving the address one does not find the place. Feeling that the driver was not going to the proper place I told him the address : “Chatto Windus & Co. King William 4th Street W.C.” Then he found it was “William IV Street”! I was fortunately on time, though it cost me a good sum. The Secretary informed C. Day Lewis on the phone and I reached the office room upstairs in a lift. At the entrance I met a rather heavily built person with spectacles, “May I know who you are?” I asked. “C. Day Lewis,” he said. I looked at him for a moment with curiosity and keenness.

We sat down in his office and I recounted to him Sri Aurobindo’s life and work. I also explained to him the purpose of my visit. As to poetry written now, I told him that his own and that of Herbert Read and Stephen Spender had many signs of the trend Sri Aurobindo had prophesied in his book, The Future Poetry. I referred to his “Magnetic Mountain”, “The Word Above All” and “The Poet” and other poems which had struck me as embodying the trend foretold by Sri Aurobindo. He was surprised to find somebody quoting his own poems rather easily. I showed him a copy of The Future Poetry, and told him, “It advocates a new way of evaluating poetry. Sri Aurobindo has introduced in evaluating poetry an essentially Indian element which makes his book a special contribution. There is also his essay ‘On Quantitative Metre’, which has failed to attract the attention of poets and critics in England. I am sorry for it. Besides the two volumes of Collected Poems and Plays he has written two epics Savitri, a long one dealing with an Indian subject, and Ilion depicting a sequel to the Iliad. He has written this latter epic in quantitative hexameters on a new principle. It is a matter of regret that the English world is ignorant about his contribution to the English language and literature.”

He said: “Why don’t you write an essay or an article in some magazine here?” “I can always write and I have written; but if somebody like you writes about it then it would be more acceptable to the British public. My request to you is that you go through his poetry and other literary works and then write what you feel about them.”

“I am crushed under a heavy load,” he said, “I am a director of this company; then I have the professorship at Oxford. I have to earn my bread and butter.”

There was silence for some minutes during which I marked that he had three vertical lines, not parallel, on his forehead; but his eyes were those of a poet.

“Do you go out of England?” I asked him.

“I hardly get a long time for it. At the most I can have three weeks. According to present arrangements I spend three weeks at Oxford and one week here in London,” he said.

I commended him to read some parts of the The Life Divine to get an idea of Sri Aurobindo’s prose. I traced, in short, the main line of thought and at the end concluded by showing that man has consciously to participate in his own further evolution to a new consciousness.

He listened with attention and was glad. He said: “I thank you for the two books. I will try my best to read them.”

I got up, he came to the lift to bid me good-bye.

“If you come to India I invite you to visit Pondicherry.”

The lift was very narrow and it was taking time to come up. I said: “I do not always like these lifts.”

“I often feel them like a prison,” he said. “Till I reach the top or the bottom I have the fear of being held up somewhere in the middle.”

CAMBRIDGE : 9th SEPTEMBER 1955

There was a letter from Morwenna Donnelly that I should reach Audley End, where she was staying, on the 7th afternoon and that she would drive me on the 9th to Cambridge, which is not very far. My appointment with the Vice-Chancellor was on the 9th. I reached ‘Audley End’ by 6.30 p.m. and saw Morwenna in person for the first time — a beautiful young lady — with a friend of hers, on the station. I had two heavy suit-cases which I got accustomed to carrying myself as there are no ‘Coolies’ in England.

‘Saffron Walden’ is a village in Essex, but a village in England is so different from a village of ours that there is hardly anything in common except the name. Roads, water, electricity, cleanliness and other modern facilities are available in the villages. There is a garden or open space to each well-built house. The upkeep of the house, earning one’s bread and maintaining regularity are so taxing that one hardly gets time for anything else. The week-ends are filled with individual and social commitments and appointments; there is hardly ‘leisure’ in the sense of available idle time· All activities outside earning bread-seeing a museum, or marketing, or picnicking, travelling, etc., — are kept for the week-end.

Morwenna’s house is in the Tudor style. To keep up the Tudor character of the house is a very important part of the life of Morwenna and her husband Mr. Collins. It is a kind of ritual. All changes in the house must not alter its character. The owners of such buildings take legitimate pride in them. This attitude is common throughout England. As a result, even though the people live like isolated individuals, there is a historical and cultural continuity. Besides, people meet at church or at common village functions and festivals. It costs them to maintain the form of the house and at the same time to take advantage of modem facilities like the telephone, electricity, radio, etc. But people don’t mind spending money for that.

At dinner we had a very nice talk about Sri Aurobindo. During the talk Morwenna maintained that in Europe also, as in India, there were people who could sacrifice or renounce things for spirituality, which I know is true. Only, their number is not very large and the prevailing atmosphere and values of collective life are not congenial to the growth of spirituality. We talked up to 11.30 at night and having discussed a wide range of subjects ended with a short meditation before we retired.

8th SEPTEMBER 1955

I saw the garden round the house. A lotus-pond, fine roses, the ground covered with turf. There are apple trees and on one side a fine vegetable garden; there are cattle and poultry to take care of. Servants and labourers are hard to have and they are costly. So the two of them have a hard time to keep the house going.

I had a heavy task this day. Twenty-seven packets of books had arrived from Pondicherry and I had to open them and arrange the books in sets. In the course of our talks I found out that Morwenna had not read the Collected Poems and Plays of Sri Aurobindo. Savtri she found rather long. She remarked that the poets in the Ashram seemed to be busy with ‘Golden Light’, ‘Blue Sky’ and ‘Infinite’. “Why do they not write about the bee, the flower and the ant?” she asked.

9th SEPTEMBER 1955

I started at 10:30 in a car for Cambridge and reached there at 11:15. During the drive we talked of India’s poverty, absence of collective consciousness, increase of population, the five-year plan, etc.

We met the British Council staff. I saw Pandit Rishi Ram on the road — he was surprised to see me at Cambridge. He was giving a course of lectures on his own. Cambridge has narrow roads like Oxford but more quiet — less boisterousness. Old colleges on narrow roads are there as in Oxford. No one dares even to imagine that the buildings can be pulled down to widen the roads — the English are conservative and yet progressive. These colleges began as religious institutions and all the signs of the old atmosphere are maintained, though religion itself has undergone radical changes.

I met the Vice-Chancellor, Mr. Henry Willink, at 12 o’clock for about 40-45 minutes. I explained to him the object of my visit — Sri Aurobindo’s connection with Cambridge and with King’s College, his stay there from 1890-1892, etc. Also incidentally I recounted to him the works he had written. He told me he had not visited India and informed me with justifiable pride that when Jawaharlal Nehru had come he had found at the lunch that four of his staff had been Cambridgemen.

He phoned to King’s College and fixed up an appointment with the Vice Provost, John Saltmarsh, at 2-30 p.m. He had ordered sherry for us but when he found that I did not take wine he ordered orange squash for me. After our meeting he took me to the little lawn and introduced me to his wife, his daughter and son-in-law. When I invited him to visit India he said he had only flown over it. We had a nice time with the children and before I left I presented a set of Sri Aurobindo’s books to the University in his memory. I expressed the wish that the set might be kept apart as a unit. He looked at the books and said: “This is a library.”

After this I had lunch with Prof. Mrs. Von Lohaizon. We talked about Sri Aurobindo’s Vedic interpretation, Kapali Shastri’s commentary and other subjects.

At 2-30 I reached King’s College. Just at the entrance I saw Mr. John Saltmarsh with his scholar’s indifference to dress and his great kindness and courtesy. He took up the suit-case I was carrying despite my protest. He was sorry that the college was on vacation and so there was very little to see. I expressed my desire to see the records. Before we went to his office he took me to the famous chapel of King’s College. It is famous throughout England. It is magnificent. Kings Henry VI & VII had built it and the building work had lasted for 80 years. Its length and breadth and height and the wonderful arches contribute to the impression of grandeur. Thousands of squares of stained glass windows on both the sides when lighted from the outside produce a very happy impression.

Then we went to the Registrar’s office where the official had kept ready Sri Aurobindo’s records as a student. In the last column of “remarks” I was surprised to find the mention of his prosecution for sedition in 1906 ending with “acquitted”. This is only one example of the meticulous care in keeping records, as in everything else, at these hoary institutions. The prosecution took place in 1906 whereas Sri Aurobindo had left Cambridge in 1892!

Then in the Vice Provost’s office I saw plans of the scholars’ boarding-house. There in “King’s Lane” Sri Aurobindo’s name written as “Ghose” was in the plan of the room. And the same room was ‘vacant’ in October 1892, as he had left Cambridge for London.

We went then to the boarding house; the Vice Provost opened with his key the room once occupied by Sri Aurobindo and showed it to me. Standing in silence for two minutes I was deeply moved: Two years of Sri Aurobindo’s life here! Where India and where England! Where Pondicherry and where Cambridge! What mysterious links work in life! How did the young man who had been completely kept away from Indian culture happen to become the spiritual guide of his country and all humanity? Mr. Saltmarsh was noticing my silence with great sympathy. I had to confess to him: “I am deeply moved.”

“I understand,”’ he said.

I saw, afterwards, that Sri Aurobindo had already got a place in the heart of the Vice Provost, for he went out of his way to give me all help in the matter of securing photographs of the register and of the room also.

I got information about Oscar Browning. In the Library I saw the application by Sir Isaac Newton to the King as the King’s appointment of him as Provost had not been supported by the Executive of the University. His application to the King against their non-election did not succeed.

All the students that have passed through Cambridge from 1752 A.D. to the present year are listed in alphabetical order in a series of volumes.

I met Pt. Rishi Ram and had dinner with him at 30 Kimberly Street. We had a long walk during which he plied me with many questions. He was much impressed by the organisation of collective life in England but his constant comparison with conditions in India was rather not just. England had an empire over which the sun did not set — it is a small country with a great nation. But India is hoary and idle and poor. Its freedom was won only the other day. She has to catch up with the modem world in many things. She must have time — that was one point I pressed.

Besides, these advanced nations have also to pay a price for their “progress”. Economic organisation is not all in a culture. Both East and West can learn from each other but no good can come out of mere outward imitation. The very climate of England dictates certain life-conditions — e.g. houses with doors closed. In India we require opening to the outside air.

The English know how to make the most of their slender natural resources: the small stream, called “Cam”, when it passes near or through a town, has both its sides protected by cement bars or by wooden planks that would not rot in water. The water is hedged in at a height and collected to flow evenly throughout the year. At places the narrow river is extended by dredging the land and using the extended water surface for keeping boats for rowing.

APPENDIX

From the Vice Chancellor of the University.

The Master’s Lodge, Magdalene College, Cambridge.

7th September 1955

It would be a great pleasure to meet you if you could find it possible to call at my Lodge at noon next Friday, September 9th. I hope that this may be possible for you.

Yours sincerely

Henry Willink

*

From: Prof. Basil Willey.

Pembroke College, Cambridge.

(Telephone: 5086)

20.11.1955

Dear Sri Purani,

Thank you very much for your letter, and for so kindly sending me copies of The Life Divine and Sri Aurobindo and his Ashram. It should be possible from these to gain an adequate preliminary knowledge of Aurobindo’s life and views.

It was a great pleasure to meet you, and I shall always remember your visit with great satisfaction and interest. I did not in the least mind standing up while you read me passages aloud — in fact, I liked this for its naturalness and informality.

All good wishes and kind regards,

Yours sincerely,

Basil Willey

*

Ashdon Hall, Saffron Walden, Essex.

Oct. 22nd 1955

My dear Purani,

Thank you for a lovely morning yesterday and for sparing so much of your precious time with me. It is the greatest joy to me to be able to hear first hand about Sri Aurobindo; you know I could go on listening for ever !

Morwenna.

*

Ashdon Hall, Saffron Walden, Essex.

Nov. 30th 1955

My dear Purani,

I feel so sad that you are going away in the flesh if not in the spirit, and that we shall no longer have the pleasure of welcoming you here, at least for the present. You have done a fine work here, stirring us all up and putting people in contact with one another; not to mention all your other achievements like the broadcast.

I am sure that Clare, Doris, Margaret and myself will be able to go forward now with resolution. We did need encouragement, and perhaps weren’t really ready until now to make a concerted effort. We have always felt it was so important to go slowly and not to act at all unless we had an inner direction to do so. It is so easy for Westerners to rush into “doing”, initiate societies, give lectures and otherwise engage themselves in activity, without any of it having a true foundation in disinterestedness — just a jolly round for the ego ! In the end these kind of organisations always fall apart and we felt it was vital not to be drawn into making that mistake and to discredit what the Master stands for by a failure.

Do come back to us in the not too distant future. We shall need many contacts with our Indian friends, specially those who were close to Sri Aurobindo …. Please tell Mother to send us an emissary now and again.

Well, dear Purani, it has been so lovely to meet you — or is it really to remake an old acquaintance that we were brought together? I feel it must be so, because you don’t feel in the least like a new friend to me.

All my love and good wishes for a safe and pleasant journey.

Morwenna

*

THE OXFORD COLLOQUIUM FROM 15TH SEPTEMBER TO 25TH SEPTEMBER, 1955

Oxford, like Cambridge, is an old seat of learning which has given leaders to England in many walks of culture. To literature, science, industry, politics, its contribution is outstanding. The Thames passes through Oxford and one notices here again how much the British people exploit their slender natural resources. One sees in the river here, as one sees m London, a number of white swans floating-a very fine sight in the morning. The Thames is between 30-50 feet broad; its banks are protected by cement planks. The people have managed to utilize the small stream for rowing purposes and for transportation. One can travel by the Thames from Oxford to London.

The population has increased almost 50% Oxford has 32 colleges on old narrow roads. The British are conservative and believe in progress in keeping with their conservatism. For instance, in all the college buildings the material used is sandstone. In the climate of England it gets corroded in five or ten years. Consequently, the work of renewing the surface with new sandstone goes on throughout the year. The people here do not even think of using granite or cement. And in the Bodleian Library here the old part in oakwood is yet kept as it was, but we find telephone, lift, electricity, heating arrangement, all up-to-date equipment, in it.

The life of the students is rather hard — one can see them going about with bags or books on their shoulders or riding on cycles — one has to be self-reliant. There is a hierarchy of teaching staff — Tutor, Senior Tutor, Don, Lecturer, Professor, etc. — who have executive authority. The students learn discipline from the atmosphere. The food is spartan in its simplicity. The professors have their rooms in the colleges where they stay during terms. They go on with their work even if there are no students in their departments.

Almost all professors are specialists in their subjects and evoke in earnest students genuine devotion. I had an experience of this while I was in the steamer. There was a co-passenger, Mr. Ellingworth, an Oxford graduate, with whom I became familiar. Learning that I was going to Oxford he gave me the name of Prof. C. S. Lewis and wrote it on a blank envelope. On my asking him to give me his own name he had to use the same envelope. He did so with hesitation and said: “I am compelled to write my name on the same envelope but it does not mean I am his equal or that there can be any comparison with him.” He had been a student of Prof. C. S. Lewis.

Wide green lawns is a speciality of all colleges here. The university maintains a department for the lawns. Universities are independent bodies and send their representatives to the Parliament. Almost 75% of the students receive scholarships. The universities furnish corps of soldiers and officers during wars. My objective was to participate in the Colloquium on “Contemporary British Philosophy” and to come in contact with leading thinkers. Two characteristics of the Colloquium may be noted. The sessions usually began at 8-30 in the morning and, as it was cold, all the doors had to be closed. Within five minutes of the beginning almost everyone used to begin smoking. The main speaker himself would begin to smoke within 15 minutes. Imagine a hall 25’-25’ in which about 50 to 60 persons smoke within closed doors! I had often to open the window for fresh air or go out to save myself from the smoke. I used to wonder at the inability of these philosophers to check smoking for about three or four hours during the session! At least one expects the main speaker to do without smoking during his address.

The other observation was that of a wide gulf between life and philosophy which existed in the life of those who participated in the Colloquium. This is not to say that one ought not to relax in life. But the way the whole company behaved in the closing “sherry party” brought to my mind in a very striking manner the contrast between life and philosophy. So long as the distance between them is not bridged I am afraid philosophy will remain barren.

THE OXFORD COLLOQUIUM

The British Council was responsible for this intellectual event and I think it could be congratulated on the achievements of this conference. There were many from Oxford and quite a few scholars from abroad. The arrangements were as perfect as could be desired. Mr. Tomlin, Mr. Bach, Miss Tingley were unsparing in their efforts to make life and work as smooth as could be made. It could have served a double purpose if other schools than the Oxford school had been allowed to ventilate their views. To an outsider it might almost seem as if it was mainly to put forward the Oxford school that this Colloquium was arranged; but perhaps it would be uncharitable to take that view. Besides the hours devoted to reading of papers and discussions there were many precious opportunities afforded for making useful contacts, which I believe is perhaps the most important result of such conferences Looking round, one finds that of all the schools of contemporary British philosophy the Oxford school is the most dynamic, and vocal and is trying to occupy all important seats of philosophy teaching throughout the British Isles. Its leaders are Russell and Moore and there are as many as sixty men teaching philosophy more or less under this leadership, but with all this it must be said that the discussions were conducted on a high level and in a very friendly spirit.

It was a source of joy to see those who participated in the discussions free from all petty jealousies and meeting each other on a plane of intellectual detachment. It would also not be correct to say that there is unanimity of views on philosophy among all those who are working in the field at Oxford. There are internal differences of outlook. Prof. Price and Prof. Weisman are only two among several who hold different views-perhaps fundamentally different views on philosophy.

To me it seemed that after Bertrand Russell, Oxford has evolved a technique of its own and philosophers want to reduce all metaphysics to this technique. I don’t know whether I am right in holding this opinion. But it was evident that there was a great pressure on all those who were present there to get this technique accepted. But, for one who does not belong to this school, to accept this technique would be to yield more than half the points, because this very technique requires consideration, examination and scrutiny. It is strongly supported by the scientific method. The greater part of its outlook is dictated by science. Victory of science all over the world and its expanding influence has in a sense, legitimately but to my mind more strongly than it ought, influenced its outlook and attitude. The scientific method contains a great truth but the question is not whether science has a truth or not, but whether the scientific approach-that is, from outside to inside-is the only way to philosophic thinking.

The Oxford school has, therefore, been trying to reduce metaphysics to common language; for according to them metaphysical problems (they call them paradoxes) arise because of the misuse, or the incorrect use, of language. So the philosopher’s most important work is to find out the correct language or the correct way of formula-ting a question.

But this attitude itself amounts to taking up a metaphysical position and I believe one who does not belong to this school would be justified in asking for a justification of this position. He may legitimately ask whether the Oxford way of formulating philosophical questions is the only way and, in the last analysis, the best way.

The Oxford philosophers seem to have arrived at analysis and reconstruction, logical atomism, etc. In all these there seems to be an effort at trying to reduce meta-physics to science. It is believed that there are basic concepts like atoms in matter, which can be known and can be formulated in simple language. Thus with the help of these “logical atoms” one could build up a system of metaphysics almost as one builds up the world of objects with material atoms. In such a simple scheme of philosophy there would be no need of so-called metaphysics which really is, according to the Oxford school, a result of incorrect or vague use of language. In fact they almost want to prove that metaphysics could and would ultimately be reduced to science. With this view they try to study ordinary language and ordinary expression but paradoxically when they have done that and give us their “analysis” and “reconstruction” they tend to move away very far from ordinary language. The same thing happened to the scientists in the last century. The scientists did not accept anything like soul or spirit but they affirmed and they accepted matter on the basis of sense evidence and they promised that they would give us a model of this material universe at the end of their researches. After about 150 years of scientific progress it was found that matter was becoming undefinable and far from giving a model of the material universe which the man in the street could understand the scientists ended by giving a mathematical equation which perhaps only a few experts in the world could under-stand. A similar predicament seems to have overtaken or is overtaking the Oxford school, for I do remember during more than one sitting learned professors coming and talking in a language so special that even students of philosophy found it hard to follow. There was no question of their being understood by the ordinary man. To what extent this extreme emphasis on “analysis” can take us can be seen from the fact that in one sitting nearly sixty of us devoted not less than four hours to the paper and discussion on “what is a word and what is a sentence?” If philosophy allows language to take precedence over thinking, insight, intuition and vision, then there will be very little left for the grammarian, the linguist and the sociologist.

Their objection to the old metaphysics was on the ground of vague use of language and flight away from life but with an effort at precision m language they do not seem to come nearer to life. Leaders of this movement, like Mr. Russell, try to relate their philosophy to life by persuading ordinary men, if they can, to adopt the scientific attitude. They plead for the rationalising of scientific discoveries as the means to solve all human problems, but it is forgotten that to demand such a change of attitude in the common man is to demand a psychological change in him, and we are left in complete darkness as to how this change is to be brought about.

*

THE OXFORD COLLOQUIUM : SEPTEMBER 15-25

There was talk during the first discussion about the “conceptual apparatus of man”. The whole argument proceeded on the basis that the conceptual apparatus of man is a fixed one. Perhaps the expounder thought that during the course of human history this conceptual apparatus of man — at least of the ordinary man — is, or seems, constant. But the question does remain whether this apparatus of knowledge now used by man is capable of change or not. The range of our senses is capable of being increased by devices like the microscope, the telescope and others. Is there a possibility of a similar increase in man’s psychological instrumentation? If the present apparatus of knowledge is capable of expansion and development then all the results of man’s present range would be certainly limited in comparison with his developed psychological apparatus.

Throughout the discussions the stress seemed to be on the mode of thought and there was very little stress on the way of life according to the mode of thought. It may be claimed that this analytical philosophy is also preparing or making for a way of life. In that case all that one can say is : better to wait and see.

During all these efforts at clarification one thought that there was too much attention paid to the technique and not to the problems. Clarification, yes, but of what? Almost all the time it was past philosophers and their thought that was being clarified but one may ask whether the Oxford experts have something of their own clarified and simple. And as to analysis, one would legitimately ask whether analysis is the only or chief faculty of the human mind. Is the function of philosophy only analytic?

An important point that emerged from the discussion seemed to me to be that these Oxford philosophers worked under the assumption that whatever is physical is alone real. They seemed to want physical proof of every philosophical statement, which can never happen unless we confine ourselves to the maxim that only the physical is real. In that case what becomes of those dynamic realities of right, the conception of freedom, democracy, justice and the like? One may argue that they are actual in the physical, but can we sense freedom or reduce justice to sense-perception? I doubt very much. The objection to the old metaphysics is that instead of trying to understand what exists they try to bring into being what does not exist. But that is the whole question. What exists? To say that what our senses perceive is what exists would be to limit human experience to a very narrow field and to deprive the human being of its highest and richest cultural achievements and fields of experience.

I think I have pointed out before that analysis could hardly be considered the highest and the main work of the philosopher, nor could we accept the analytical faculty as man’s highest faculty. Analysis may help us in understanding things and their constitution by taking things apart from the whole and thus give us an insight and understanding of things but it is synthesis which is the more important faculty which leads to a new creation or a new and organic view of the whole. These philosophers are insisting that we must first know what things are but that is exactly the crux: how do we know what things are ? Besides, philosophy uptill now has been very often a way of life or at least has suggested a way of life. Does analysis stand for a particular way of life except, of course, the scientific and materialistic one which stresses the outward and external as the only real?

Throughout it was very difficult to find out what all these philosophers wanted to clarify. It was all along somebody’s statement or proposition or paradox, as they called it, which they wanted to clarify. Of course that process seems to give them a position of advantage with regard to all formulative philosophy. They want us to believe that the real function of philosophy is not to hold any views at all about reality or about man or life or anything but to go on examining every statement, proposition and paradox. And, secondly, they seem to insist on common sense which generally amounts to the acceptance of the world of physical reality as the only one. Besides, who is to decide what are “ordinary concepts” and what is to be understood by “common sense”? They took as an example the word “moral”. Now what is the ordinary use of the word “moral”? one may ask. But why should not a possibility of new creation or a new thing or truth being brought into existence be accepted in life and by the human spirit? I think we have to face the question whether the removal of paradoxes and perplexities is the one and most important work of philosophy.

British philosophy tries to trace is course from the critical tradition of Locke and Hume and explains its present antimetaphysical form by suggesting that it is a reaction — a conscious reaction-against the idealist philosophy. Bradley asserted that time is not real, and this statement was contradicted by common sense. I believe what Bradley wanted to say probably was that it is necessary to realise that time is not real or that the unreality of time could become an experience even though it may not be a subject of common experience or common sense. Does this not happen in the case of poets and artists?

The course of idealism has been stressed since 1870 from T.H. Green to F.H. Bradley. It may be asserted here that the passionate conviction of Bradley came from his studies in mysticism. Russell contradicted Bradley by trying to introduce mathematical or symbolic logic. It is quite certain that the work of this logic was exaggerated at the time. The criticism against Bradley and others of the Continental school was that all their statements were “pseudo-statements”, “nonsense or untestable”. The new school even asked for verification of metaphysical statements.

These philosophers are trying to emphasise “obvious truth or facts” or, in other words, “interpretation of facts”. That really seems to be the problem of metaphysical reasoning. The statements of facts which these philosophers give are in terms of mathematical symbols and from the point of view of the ordinary man and common sense one may say that they are meaningless or nonsense. We cannot say, for instance, when a poet says something really poetical that he is talking nonsense. The business of metaphysics is to give us a concept or a system of thought of the world as a whole so that one may know the world as one-something having no contradiction within itself. Of course the British philosopher would say perhaps that all such propositions are based on logical misunderstanding. But one may expect from the metaphysician not merely “a way of looking at things” but also “his proving the way of looking at things”. And while we criticise the past metaphysicians for trying to do these things, which according to the modem Oxford school amounts to recommending a way of looking at the world, we may ask the modem school whether they are, even by their analysis and reconstruction, not themselves recommending a way of looking at the world. When so much has been talked about reality and fact and what exists, it may be pertinent to point out that the whole range of human experience could be much better explained by granting various orders of the one reality. That is to say, there is a hierarchy in experience available to man which can be arranged in a sort of ladder or ascent beginning with the body or the physical, rising to life, then to the emotions and ultimately to the intellect, but intellect is not the last available term of the order. Potentialities lie beyond the intellect and evolution may be said to be the process by which these potential orders of reality available to man are made active and real.

Sometimes during the discussions one felt a question as to whether it was necessary to knock out all metaphysics and reduce everything to science in order to make a place for the contemporary British philosophy. Moore argues that philosophical paradoxes are to be rejected because they go against common sense, but in that case are we not begging the question?

Discussion on the problem of perception almost asserted that knowledge is sensorial. Therefore knowledge of sense perception was necessary for the philosopher. He was not to study perception in itself but for the sake of the knowledge it gave. The objection of the British philosophers to the past theories of perception is that they brought 1n things which existed in their own minds and did not study perception by itself. The three British philosophers, Locke, Berkeley and Hume show us the growth or development of the idea of perception.

The discussion on the I7th was more like word-chess play or mere dry logic-chopping by a young philosopher who tried to play this game for a period of more than one hour.

Mr. B.A.O. Williams on the 18th discussed personal identity. He was more clever than profound for he had not much to do with the human person and its identity. He dealt more with houses and shadows, and tried to show the part of memory in the experience of personal identity. In the sense of sameness or personality, continuation of the memory or other circumstantial evidence is not a criterion. There were apparent brilliant examples. If the shadows of two objects could coincide, have we the same shadow or can there be a difference? Is there one shadow or two? When we assert this is the same house of an Englishman that the American bought, what does it mean? What is meant by the same house? Is it the same because its parts are individual or as when one says that a religious man and a drunkard can be the same person?

*

The discussion on the 20th about causation in ordinary life could have been much more interesting than it was if Mr. Hart had tried to get deeper into human psychology and given us some understanding of how a man decides or how conduct is caused. All predication about causation or about unrealised possibilities of conduct brings us face to face with many deeper problems of each being. The question is: how does a man decide? Is he compelled or does he act freely? It is almost certain that there are many possible choices presented before the human individual at the moment when he is faced with the problem of taking a decision and it is very interesting to know what exactly makes the man accept one possibility out of several and make it his choice or decision, and there are people who retrospectively, after the act, say “I could have acted otherwise” and there are others also who can say about a man that he could have won if he had tried or even acted otherwise.

The truth about the matter seems to be that there are many personalities in the human being. That is to say, there is not one “I” but, as Stephen Spender says in one of his poems, “There is I eating, I sleeping, and all these I’s surrounding the real I.” In fact, man’s decisions are hardly of this real “I”?. Most often they proceed from the desire-self, the impulsive self, the craving self and so on, and probably the solution of how to make a correct decision might depend very much upon the growth of self-consciousness of the individual, so that if he is able to see or be conscious of the various parts of his being — and also their likes and dislikes, then he can exercise his will, or we may say choice, and allow his real “I” to act and make a choice. The meaning of the word “cause” could have been more profoundly sought. In fact, cause is not one particular event or occurrence. There is hardly one simple such cause even in the most ordinary phenomenon. Cause really seems to imply a complex of conditions precedent, and the result seems to be nothing more than a complex of conditions following. When we say the cause of a famine was the lack of rain or the failure of the Government to build reserves, what we really mean is that a set of conditions was responsible for a set of effects. Cause in the old sense was sup-posed to be the only one operative element that brought about the result but we see that even the simplest result is hardly due to such one operative cause; for, there is bound to be a number of factors active even when we do not see them or only one factor seems to be operative.

Two of the most interesting papers were by Dr. Price on “Belief and Half- belief” and by Dr. Weismann on “Philosophical Argument”. During these two papers one felt that even at Oxford there were people who had real understanding of what philosophy has to do. Dr. Price argued that half-belief need not be a disqualification or a sign of weakness. Half-belief may be mild belief or inclination to believe and these conditions of belief and half-belief alternate in the life of man due to outer and inner conditions, not necessarily due to his weakness or indecision. It may be due to vagueness or uncertainty about validation or inability to answer an opponent. It may be due to split personality or divided loyalty. Half-belief may be a state which may be described as a state of growth towards either full belief or denial.

Everyone willingly suffered the infliction of dry logic-chopping and inroads into grammar and linguistics by the Oxford philosophers. But after four or five days it was found to be too much. The daily doses of discussions for four to six hours were too heavy and dry for many and for me were bitter. The arrangement for 13 days was to afford opportunities to all to make personal contacts.

Of the group two members, Dr. Julius Kraft and Dr. Mercier, managed to play the piano in the British Council office every day at 7.30 p.m. I joined them. They used to gather pages from books on classical music and I saw that they had real interest in and capacity for playing music. I even found that they were more interested in music than in philosophy. Dr. Kraft used to participate in philosophical discussion adopting the Socratic method of which he was a great admirer and follower with detachment and subtlety. But when he sat on the seat of the piano and moved his fingers along the keys he was a different person — his whole being used to vibrate with the beauty of the harmony of the notes. The degree of self-forgetfulness which he and Dr. Mercier could experience while playing music was never reached by them in their philosophical discussions.

I told them: “You have missed your vocation. Do not give up music; the hunger of your soul will be satisfied only by music.”

We had a good talk on art as expression of beauty, and on beauty as an aspect of the Divine. “Truth,” I told them, “is not confined to rational knowledge, nor is it its highest form. Art creates beauty which is equally an aspect of the Truth, perhaps higher than that created by the intellect.” I met Dr. Kraft again in the British Museum and wanted to meet him in his own adopted country U.S.A. in 1962 when I went there. On writing a letter to his address I got no reply — it came nearly after two months, from Mrs. Kraft to convey to me the sad news of his death by heart failure in the train while travelling in the month of December 1961. I had the satisfaction of meeting her and she was happy to have anecdotes from me about his stay at Oxford.

Dr. Mercier I met again at Berne, his own place, in November 1962 at a small gathering which he had arranged for a talk.

*

MEETING WITH K. D. D. HENDERSON : 20th SEPTEMBER 1955

I had expected to find some living influence of Eastern philosophy and religion at Oxford as I knew that Mr. Spalding had endowed a trust for encouraging these studies at Oxford. The idea was to afford facility to the Western student to learn Eastern philosophy and religion in England just as the Indian student has about learning Western philosophy in India. He wanted to encourage the deep cultural interchange between India and Britain. And the first professor chosen was Dr. S. Radhakrishnan. But I was disappointed in my expectation to find some students interested m Eastern philosophy at Oxford. Oxford had retained very little of Dr. Radhakrishnan’s influence.

My reading of the situation was confirmed as I came to know that the Spalding Trust had changed its objective and got converted into the “Union for the study of great religions”.

I met Mr. K.D.D. Henderson, who is the Secretary of the Union and a very earnest seeker and a very good organiser. He ordered many books of Sri Aurobindo for the library of the Union. He has often to go to other countries and particularly to India for his work. I invited him to visit Pondicherry and he sincerely tried to comply with my request. But somehow the visit could not come about till 1964 when he came for a day.

MY PILGRIMAGE TO ST. PAUL’S [1]SCHOOL, LONDON : SEPTEMBER 26, 1955

The appointment with the high-master was fixed on the 26th of September 1955 at 2-30 p.m. through the British Council, after a protracted communication through the phone.

I came to 31 Queens Gate Terrace, finished my lunch at 1-30 and by 2 o’clock took the bus for going to St. Paul’s. After some time I found the bus was going in the opposite direction. So I had to get down and, in order to keep the time of appointment, take a taxi.

As I was approaching the school I saw men and women walking on the road and my mind went back seventy years in the past and saw a shy, dark boy taciturn and yet firm in his mind walking on the same path. Pleasures and enjoyments of life, wealth, name or comfort had no attraction for him. He was interested in reading and acquiring intellectual knowledge. I reached St. Paul’s five minutes before the appointed time.

I was taken to a room by the porter; the atmosphere indicated that it was not easy to meet the high-master. The lady secretary came and wanted that we should finish the preliminary inquiry about Sri Aurobindo and then the high-master would see me for a short time. But she said she could not locate Sri Aurobindo among the scholars. I produced the photo-copy of his record from King’s College, Cambridge, where he was mentioned as a “scholar from St. Paul’s.” I volunteered to help her find the name; but she kept the register to herself.

Then the porter took me to the high-master, Mr. Gilkes, a tall lean man who received me kindly. He helped me to remove my overcoat and we sat down to have a look at the registers.

He gave me one; fortunately within three minutes I found ‘Ghose Arabinda Akroyd’ and showed it with great joy to the high-master. He thought that I was collecting material for his life. I told him that I was collecting the materials but that I was not sure of writing his biography.

I explained to him that I had come in the spirit of a pilgrim. Sri Aurobindo had spent 14 years of the formative period of his life here and had drunk deep at the fountains of Greek, Roman and Modem European cultures. “India,” I said, “owes a debt of culture to England and so far as I can want to try to pay back the debt to England, — though he has more than paid it by showering his grace upon the English language.”

While I spoke to him about Sri Aurobindo’s vision of Life Divine, his grand synthesis not only of East and West but of Matter and Spirit, his conception of unity of mankind, I was intensely moved as I remembered the reference to his poverty while he was in London [2], when he had no overcoat to protect him from the English winter and had to go without dinner at night. I also recollected the complaint of Dilip Kumar Roy who had argued in one of his letters that Sri Aurobindo was born great and that he could not have an idea of the difficulties of ordinary mortals like hmm. Sri Aurobindo replied: “What strange ideas again ! That I was born with a supramental temperament and that I know nothing of hard realities! Good God! My whole life has been a struggle with hard realities — from hardships, starvation in England and constant dangers and fierce difficulties to the far greater difficulties cropping up here in Pondicherry, external and internal. My life has been a battle; the fact that I wage it now from a room upstairs and by spiritual means as well as others that are external makes no difference to its character.” How often do devotees and disciples misread their masters!

The high-master was seriously listening to me when a teacher called him — as his time to attend to some work was overdue. He simply replied, “Not today,” and we continued the talk.

Then he gave me some of the books dealing with St. Paul’s, registers, etc. and volunteered to show me round the school. We were going up when he said, “Sri Aurobindo must have so often gone over this and seen this very statue of Laocoon!” I remembered Sri Aurobindo’s criticism of it in The Foundations of Indian Culture. We came back to his office and he promised to give me all the help he could and provided me with the address of Mr. Cyril Bailey, who was Sri Aurobindo’s contemporary at St. Paul’s. Then we went to the prayer room; he told me Milton and Pepys had been students of this school. He requested me for an article in the magazine Pauline on Sri Aurobindo.

The interview had far exceeded the intended limits — it was nearly 4 o’clock. Before getting up to leave, I said: “I would like to read to you one of his poems so that you may feel how rich is his contribution to the English language.” I read aloud in slow movement “The Rose of God.” He was thrilled by the mastery of language and the grandeur of the vision. He asked me to sign the book of visitors. I did and when I was leaving he came to bid me goodbye at the gate. While we were going, boys marched past us in files of two. The high-master called out “Shah!” A young boy from Bombay, Vikram Shah; stepped out and saluted. The high-master said, “He is a clever boy.” I told him: “Remember that in this school where you are studying great men of England and India have learnt; Sri Aurobindo was a student here.” At the entrance he opened the door for me and bade me a very genuine “au revoir”.

I felt that my visit to St. Paul’s had really become a pilgrimage.

The relation thus begun went on increasing during my stay in England. I went and saw Mr. Cyril Bailey at his distant house in “Wantage.” Mr. Bailey has been connected with St. Paul’s for over 50 years.

I wrote to the high-master after my visit to Mr. Bailey. On 18th October 1955 I received the following letter, an invitation to lunch at St. Paul’s:

‘I was delighted to hear from your letter that you had had a talk with Dr. Cyril Bailey. I know he will have been glad to renew his many happy memories of this school, and I felt convinced that you and he would get on well together …

‘I do not know whether you would care to pay another short visit to the school before you leave. If so I would suggest that on Wednesday, 26th October, you call here just before 12-30 p.m., that you face the ordeal of school lunch in a room where Sri Aurobindo used to have lunch …

Yours sincerely, A. N. Gilkes.

I went to the school on the fixed day at the appointed time. In a large hall about 400 students were making noise with their spoons and forks and talking busily like chirping birds. The food served was spartan in its simplicity. I was given a place on the dais with the high-master, his wife and teachers, from where we could see all the students. I was trying to take my lunch with the constant thought of a young boy taking his daily lunch here from 1884 to 1890!

When my time for departure from England was fixed I wrote to the high-master about it. A letter dated 25th November 1955 was received:

‘Many thanks for your letter containing the article for the Pauline upon Sri Aurobindo; it is very good of you to do this, and I was delighted with the article itself; it will make a fine contribution to our next number, and I have shown Mr. Richards your letter, who will first of all write to you and send some copies of the Pauline containing the article, which will appear next term.

‘I am most grateful to you also for the books; you have done service not only to the school, but also for the mutual understanding between East and West. I shall not readily forget the pleasure and interest that my first meeting with you excited. I thank you for this great occasion, and I send with you the best wishes not only of myself, but also of the school community, to encourage you in your great work.

A.N. Gilkes.

[1] St. Paul’s School was started by Dean Collect in 1509, near St. Paul’s Cathedral. But it was burnt in the Great Fire In 1884 it was brought to its present site in South Kensington. It is an old institution like the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. The school had 12 teachers and 211 students and high-master in 1884. Dr Walker came from Manchester school as high-master in 1876 and worked till 1905 when he retired. The school has 153 scholarships.

[2] In the memorial which his well-wishers persuaded him to write there is an autobiographical note of deep pathos relating to his financial embarrassment: “I was sent over to England when seven years of age, with my two elder brothers, and for the last eight years we have been thrown on our own resources without any English friend to help or advise us. Our father, Dr. K. D. Ghose of Khulna, has been unable to provide the three of us with sufficient for the most necessary wants and we have long been in an embarrassed position.”— 21 November 1892.

While in Pondicherry we were watching the wayfaring of our Vivekananda in 1955 England, we received Puraniji’s first-hand experience at the Ashram Library. Then his book SRI AUROBINDO IN ENGLAND came out!

Thanks Anurag. Such yeoman service to preserve the Glimpses of the life of master(s) and key disciples,

Chandra

Pdf file must available so we can download the diary

Congratulations. Very precious. I had brief interactions with Purani on a couple of occasions. What a privilege for him to have been so intimately associated with Sri Aurobindo! He might have been Sayana in one of his previous births and now come here to correct himself; but his Approach to Savitri will always remain one of the most precious gifts to us.

Nine years after Puraniji, I too had made a visit to King’s College, Cambridge in the hope of seeing something of Sri Aurobindo’s time there. I was then studying at the University of St. Andrews, and during the summer vacation of 1964 I was doing a summer job at the BBC in London. So one fine summer morning I took the bus to Cambridge and proceeded to King’s College. I went up to the porter’s lodge and told him about my interest in Sri Aurobindo and I was directed to the Office of the Vice- Provost – the same Mr. John Saltmarsh that Puraniji has mentioned. At this time I had no idea of Puraniji’s prior visit here but I was struck by the immediate connection that he made with Sri Aurobindo. He never did mention Puraniji’s prior visit but immediately took me on a tour of the college, starting with what he called “a scrapbook on old students”. This must have been the same register that Puraniji had seen. However there was big patch and Mr. Saltmarsh explained that the patch was where a newspaper report on Sri Aurobindo’s “seditious” activities had been pasted. However, when they found out about Sri Aurobindo’s later achievments (from Puraniji, no doubt) they had removed this article. Instead there was mention of Sri Aurobindo having been nominated for the Nobel Prize. I took a photograph of the “scrapbook”. He then took me to the rooms that Sri Aurobindo had occupied. In Cambridge Sri Aurobindo actually had two small rooms across a corridor, one was his bedroom, where visitors were not allowed , and the other was a sort of study room where he could have visitors. I took photos of both rooms and the view from his bedroom that looked out on a part of the college quadrangle. From there we walked through several corridors to view the dining room and a classroom which Mr. Saltmarsh indicated had not changed much since Sri Aurobindo’s days and where he must have attended classes. The classroom had very old wooden bench seats and I knew how uncomfortable they were because at St. Andrews (which was almost as old as Cambridge, dating from1418) I had used similar classrooms. On our walk through the college, Mr. Saltmarsh pointed out to me portraits of professors who were very likely to have taught Sri Aurobindo and I took some photographs of them, including one of Oscar Browning. Later, Mr. Saltmarsh ended by escorting me through King’s College Chapel, which is one of the most famous such structures in the World,

Now that I have read about Puraniji’s visit, I think that following that visit, Mr. Saltmarsh must have researched Sri Aurobindo’s stay in Cambridge a little more, because the very direct and comfortable way in which he took me around.

Many years later I was asked to give a talk at the Ashram on my visit to Cambridge, and after that I digitised my old photographs and handed the, over to the Ashram archives.

One final remark about studying in those old and uncomfortable classrooms. Many generations of students had passed through these rooms for centuries and some of them had scratched their names on the wooden desks attached to the semi-circular benches, At St. Andrews I had sat where two of these were Gregory (inventor of the telescope) and Napier (who invented logarithms). When later, during a visit to Pondicherry, I mentioned this to my mathematics teacher there, Sunilda, he remarked on how exciting that must have been. Yes indeed! (now, Sunilda and mathematics, what a wonderful and mostly unknown story of human development that is!! but not for today)

I must also mention that I and, later, my wife Ruma were the recipients of immense love and affection from Miss Doris Tomlinson, whose name is mentioned by Puraniji. Doris was one of the founders of what I believe is the first London Sri Aurobindo Centre which I used to visit during my summer stays in London. During my time there in the 1960s, she was mostly unwell and resided in a nursing home. We members of the centre visited her from time to time and drank of the wonderful atmosphere that prevailed around her. When I visited Pondicherry during 1966, she suggested that I get Mother’s advice about what we should be doing in the centre. Mother;s reply was simple: to read Sri Aurobindo’s and Her books and have a short meditation but there should be no discussion or explanation of what was read. This was in conformity with a much arlier message that I had received from Sri Aurobindo.

“Mother’s reply was simple: to read Sri Aurobindo’s and Her books and have a short meditation but there should be no discussion or explanation of what was read. This was in conformity with a much earlier message that I had received from Sri Aurobindo.”

With this information, I wonder why we have today so many persons who interpret or explain Savitri. Of course, there are Savitri reading-study groups, and there have been and there are Yogi-individuals among us who exquisitely interpret texts from Savitri, however, the ultimate reading of Savitri is a yoga meditation of reading, absorbing, assimilating and let the inner being expand by this discipline in all its Stillness.

A.B. Purani’s England Diary is marvellous to read. I find it striking that he kept a respectful and even admiring attitude toward a country that colonised India for so long. That must reflect the depth of a soul that understands the whole of story of Life, inspired by Sri Aurobindo himself.

“I wonder why we have today so many persons who interpret or explain Savitri.”

Why “Savitri” only? It is true for all of their writings and conversations. Isn’t it?

Yet why interpret? One deeper answer is, it is an occasion for oneself to deeply remain in their ambiance and their consciousness, to absorb and assimilate it and to let it work within oneself. It has the power to bring about the alchemic transformation, acting like a silent yet dynamic mantra. It is brooding over it, it is concentration, it is meditation, it is tapas, by which interiorisation becomes profounder and operative. It is a means for inner and wider growth, bringing even a kind of globality.

But then why write and discuss with others? publish in journals or write books or freely distribute PDFs? Why seminars, retreats, conferences, meetings, websites like the present one, OF? And didn’t they encourage questions being asked?

Surely, it is to develop that mutuality, that globality to expand, to spread, it bringing back newer dimensions of perception and understanding. To remove mental clogs, to illumine discernment and comprehension, to widen intellectual horizons, to dismiss prejudices and predilections, are legitimate early means for entering into the spirit of immense things. The gain could become mutual, even universal.

There is absolutely no doubt that Sri Aurobindo’s knowledge was encyclopædic and to get the nuances and significances one has to have a broader basis and thorough preparation. There the exchanges can help.

Let me give one example from “Savitri”, Book of Yoga, Canto Seven (p. 553; 131.16, 16th sentence of the Canto). This is in the context of Savitri’s Yoga, the all-commanding position she has already attained.