Dear Friends,

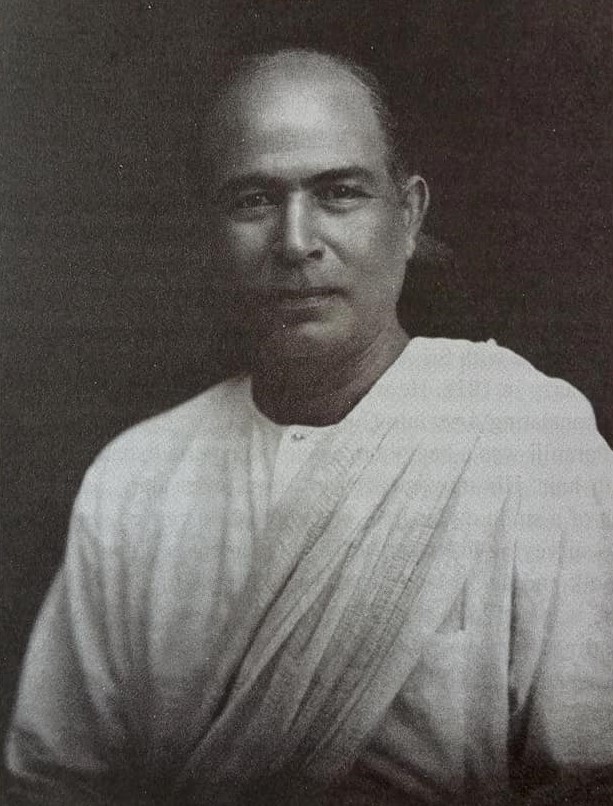

Ambalal Balkrishna Purani (26.5.1894—11.12.1965) was a Gujarati revolutionary who met Sri Aurobindo in 1907. A graduate from St. Xavier’s College (Mumbai) with Honours in Physics and Chemistry, he established a chain of gymnasiums in various parts of Gujarat. He went to Pondicherry in December 1918 to meet Sri Aurobindo who assured him that India’s freedom was imminent. He visited Pondicherry again in 1921 and joined Sri Aurobindo’s household as an inmate in 1923. Posterity would always remain grateful to him for keeping detailed notes of the ‘Evening Talks’ Sri Aurobindo had with His disciples. His duties in the Ashram included answering correspondence arriving from Gujarat, preparing hot water for the Mother’s bath at 2 a.m. and meeting aspirants who were keen to know about the Integral Yoga. He became Sri Aurobindo’s personal attendant when the latter met with an accident in November 1938. After Sri Aurobindo’s mahasamadhi, he took some classes in the Ashram School. He visited U.S.A., U.K., Africa and Japan to preach the message of Sri Aurobindo. A prolific writer who wrote in English and Gujarati, his published works include Evening Talks with Sri Aurobindo, The Life of Sri Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo in England, Savitri: An Approach and a Study, On Art: Addresses and Writings, Sri Aurobindo: Addresses on His Life and Teachings, Sri Aurobindo’s Vedic Glossary, Sri Aurobindo’s Life Divine, Studies in Vedic Interpretation, Sri Aurobindo: Some Aspects of His Vision and Lectures on Savitri.

In 1955 Purani visited England to participate in the Colloquium at Oxford on Contemporary British Philosophy and to gather whatever material was available of Sri Aurobindo’s life in England from 1879 to 1893.

We are happy to publish in the website of Overman Foundation the diary of A.B. Purani which chronicles his sojourn in England. The diary has been published in two parts. Here is the second part.

With warm regards,

Anurag Banerjee

Founder,

Overman Foundation.

____________

A.B. Purani’s England Diary

Part II

ROYAL INDIA PAKISTAN CEYLON SOCIETY :

29th SEPTEMBER 1955

The appointment was at 10.30 in the morning with the secretary Mr. F. Richter, a very kind old gentleman. I represented to him the need for an effort to make Sri Aurobindo’s work better known than it was in England.

He asked me about Buddhism. I had to explain to him that Buddha’s replies to his own disciples about what is Nirvana have never been definite and satisfactory for the modern mind. For instance, he gave the example of a man hit by an arrow, and said his need was not to find who had prepared the arrow but to cure the wound. It is no use asking how or why suffering is there. It is there and needs to be cured. He said: “I have the cure: man suffers because he has desires, trishna; the cure is to abandon desires!”

This is a pragmatic approach. It would be difficult to persuade the mind not to question or inquire or seek. But Buddha’s service to mankind was not small, he brought the Light to many. Each incarnation brings the Light because each has the contact and even identity with the Supreme Light. But he is also conditioned by the evolutionary stage of humanity at the time of his earthly life. So we do not know if mankind was ready for anything more at that time.

At the end of the talk, October 28, 1955 was fixed for a meeting under the auspices of the Royal India Pakistan & Ceylon Society, at Overseas House, Park Place, St. James Street, of the S.W.I.

OCTOBER 28, 1955

That afternoon the Secretary, Mr. Richter, invited me to lunch in an Indian restaurant. During the lunch he asked me about the Ashram, about Sri Aurobindo and the International Centre of Education. He took me to “L’Institute Francaise” and showed me round the library where there is a beautiful modern design painted on the wall. He introduced me to the Director who made me an “honorary member” of the Institute. A relation has been established with the Institute from that time.

The meeting was at 6 p.m. Mr. Shukla, I.C.S., the president, came late. But I had to begin the lecture punctually, after Mr. Richter had introduced me to the meeting. I expounded the vision of Sri Aurobindo to the audience. The president spoke on a quite different subject, praising the approach of the Western mind. But on the whole the impression seemed good. There were a few Indians in the audience — Mr. P.D. Mehta was one who came to express his appreciation — and also there were a few that had come from outside London.

I had again a meeting with the secretary on 11th November. He wanted some suggestions about the celebration of August 15 in England. I gave him the names of three persons who could address the meetings and also made other suggestions. [1]

LEEDS : 28th SEPTEMBER—2nd OCTOBER 1955

Staying far from London city I had to get up early to catch the first bus to Kensington and then the train at King’s Cross Station for Leeds. I reached there at 12-45 p.m. The contact with the Vice-Chancellor was made through a common friend, Mrs. Nora Heron, who had visited Pondicherry. Arun Jariwala, a young student from Surat, and the representative of the British Council were at the station to receive me. My lodging was arranged at Sadler Hall by the University where I went in the evening.

In the meantime we had a look at the Town Hall, the Museum, and the Municipal Textile College. Leeds is known for its sculpture and pottery, as well as for its cotton and woollen textiles.

On the way to the Town Hall we saw a group of people in the open, listening to someone. Joining the crowd, we saw a young man with a brass cross in his hands speaking to the people about the Roman Catholic religion, and men from the group were plying him with questions. I wanted to slink away from it as I did not like to have any discussion about the subject. One of us —probably Jariwala — asked me if I had some questions to ask. I confessed my ignorance about the various sects of Christianity. He insisted that I ask the young man some questions. I said I had only two questions coming to my mind just then : 1. What happened to men who were born before Christ, as they could not become Christians? 2. What will happen to those who to-day believe in God but are not Christians? Then we left the group.

The painting section in the museum has four or five very fine pieces — particularly one with dark and threatening clouds over the sea. There was a model of a coal mine too. Sadler Hall preserves the memory of Sir Michael Sadler who was for years the Vice-Chancellor of Leeds University. He was the president of the Sadler Commission appointed in British times to report on the expansion of education m India. He sounded, even in Leeds University, a note of warning about the insistence on science and technology that was elbowing out the humanities — poetry, arts, literature — from the higher studies. He pleaded that it harms the integral development of the individual. In this house students from all countries find a cheap lodging.

Mr. Higginson was in charge and I had a pleasant evening with him talking about Sri Aurobindo’s vision, about education and arts. I read out some passages from Wordsworth on his request. He asked me about the basic ideas of Sri Aurobindo on education.

I told him that the first thing is to accept the child as a growing soul; the child has within it the same Divine spark that the teacher has. The true teacher has to awaken that spark within himself and within the student. It means the teacher must get rid of his superiority complex. The child is not capable of using its natural instruments which it has to learn to use well and effectively; it has no experience. It is the teacher’s task to make it learn the proper use of the natural powers and also to provide the knowledge of the progress of man in his cultural growth, m the form in which the child can grasp it. The true teacher is happy in the knowledge that the privilege of helping growing souls is given to him — he has the joy and the satisfaction of that knowledge.

The second thing is to remember that the child learns: the teacher does not teach, he only helps the child to learn. He has to present various subjects before the child and should cultivate m him the power of finding out those that interest him.

The programme of my visit to the University was fixed on 29th September 1955, from 1 o’clock to 5 p.m. This included visit to the Registrar, the Library, the Department of Philosophy — lunch with the Vice-Chancellor and senior professors, visit to the textile and engineering departments, visit to the seniors’ common room. I returned to Sadler Hall with the British Council representative.

I reached Parkinson’s Hall at 10-00 a.m. with a suitcase containing Sri Aurobindo’s works. The assistant registrar showed me round. Parkinson’s Hall is a very imposing building of marble from Sweden carved here into high pillars and fine slabs. The hall is used for entrance and for gatherings by the students and round the hall are situated various departments. Leeds is a recent university compared with Oxford and Cambridge; Leeds regards them as old, antiquated and prides itself on being modern.

The library is a circular structure in which cupboards are fitted, filled with books : there I saw the original edition of Descartes’ works, Shakespeare’s folio edition 1623, Euclid’s geometry printed in 1438 with figures in the margin, the first edition of Newton’s ‘Principia’. Then it dawned on me how slowly, through the centuries, scientific knowledge has gained ground in Europe.

There was one thing which was very interesting: a box 2” x 1” x 2” in thickness — like a small attache-case, containing 40 or 50 miniature books each 2” x 2” (like the Gita in a thumb-edition that we have); it was called the “miniature library” for a man. It contained classical works and books that a cultured man should read. In old times when men went on travels they carried this kind of miniature library with them.

In the philosophical department I met Prof. Toulmin, and I expressed the hope that the students who attended the university would make progress in their studies proportional to the grandeur of Parkinson Hall. He said: “Look at this department; how strongly built it is with brick and mortar. Now in the new craze for big buildings there is an idea of demolishing it, whereas the staff would hardly get facilities for working so quickly.”

I said: “My observation is that when the laboratory moves to imposing buildings, the fundamental research is diminished. But I do grant the need of proper equipment for modern research as it is hardly possible to work under the conditions in which Faraday or Richard Arkwright worked.”

The laboratories at Leeds are equipped like small factories. In each department experiments are carried on to improve industries — wool, cement, artificial silk, different methods of generating electricity, the engines, processes of dyeing. In each department students work and it depends on each one how much or how well he learns. In my talk with Prof. Toulmin I drew his attention to Dr. Sisir Kumar Maitra’s book on Sn Aurobindo.

As the lunch-time was approaching we went to the Professors’ common room, where I met Sir Charles Morris, the Vice-Chancellor, who led me to the dining room where seven or eight men of the university joined us. I was glad to find his attitude to India sympathetic. During lunch the subject of the international situation came up. I participated in the discussion and bore the brunt of the talk. I said:

“The current idea seems to be that the fulfilment of man’s collective life is in its economic progress. It is a half-truth. The collectivity is not something inconscient, it is a developing being. In the beginning, like the individual, it struggles to maintain its existence; economic organisation of collective life is its means to that end. From stability of collective life it turns to prosperity. But economic prosperity is not its supreme aim: economic organisation is the necessary basis but not its sole end. Different collectivities have developed diverse strains of culture; Europe — with England in particular — has given social and political values — ideals of freedom and equality — to mankind. India has developed her own strain of culture in which ethical, religious and spiritual values govern the other values of life. As a solid economic basis is necessary for effective collective life so are the spiritual values indispensable for any collective perfection and fulfilment. In a sense it may even be asserted that spiritual values are more important than mere economic values. The unity of mankind that is already coming would gain immensely in its cultural life by the distinct contribution of each culture — diversity would add to its richness. The difficulty is that this collective consciousness, now functioning as the national consciousness, strives — like the ignorant individual — to satisfy its desires and ambitions. It is these national egos that create world-wars. It is after two world-wars that the self-complaisance of modem man is shaken.

“The trend of Nature, as seen in so many events today, is towards unity of mankind — that being the largest and the last unit‘ of collective life possible on earth. This unity of humanity will not come about merely on an economic or constitutional basis — though that will play its part in it. It will necessitate the acceptance of the Truth of man’s divinity : it is this that can make dynamic the brotherhood of man. The U.N.O. is weak to the extent to which it is dependent upon its constitutional rules and regulations. Those who participate in its workings must be moved by a feeling that humanity is a family, without any distinction of big or small nations. It should not be treated as a chess-board for securing support to a point of view or for creating a party. The problem is: how to organise human life in such a way that mankind can progress peacefully towards its goal of perfection. That would necessitate great changes in its outer moulds of life, but in order to be fruitful they must come as a result of an inner change.

“This might look like an empty dream at first, but it is not impossible to put the ideal into practice even under the present difficult conditions. For instance, it is possible to remove the walls that divide nations before the unity of mankind is achieved — the customs barriers that exist between France, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland can be removed and the income to the states can be worked out on the basis of past averages-the charges being collected at one point. Mr. Churchill proposed a common citizenship between England and France during the last war; it should be easier to carry out the ideal of multi-citizenship now in peace, e.g. the English, the Africans and the Indians who live in East Africa can have triple citizenship. It is natural that there should be difficulties in carrying the idea into practice. On the other hand preparations for an all-out atomic war are not quite easy.”

Sir Charles Morris asked me about the International Centre of Education at Pondicherry and was happy to know that co-education is carried out there from beginning to end.

He took me to his office after lunch; I took the suit-case containing books of Sri Aurobindo and presented them to the University and requested him to keep them as a separate collection in the Library. I drew his attention to the The Ideal of Human Unity and The Human Cycle and The Foundations of Indian Culture as the books which he might go through. In the afternoon I met Prof. Jefferson and had a talk about modern poetry.

30th SEPTEMBER

Lunch was to be at Arun Jariwala’s place and I had volunteered to cook as he had to attend his classes. Rice, Legume, cabbage, Halwa, etc., were prepared and we had lunch at 1 o’clock. We met Mr. and Mrs. Joceline, Quakers, at their place. We had a look at the stream of water which is made to pass through three small lakes. The water was gathered into the last one by a dam and the expanse of water was used for rowing and boating.

1st OCTOBER 1955

In the morning I went with Mr. Sousmarez, in charge of the art department, to see Lord Irwin’s estate “Newsman”. It reminded me of the Rajput castle of the middle ages. The Irwins played an important role in those early days. Large rooms for dancing, furniture of the 16th-17th-18th centuries, sculpture, painting, wall decorations — the estate was like a museum surrounded by extensive lawns on the high ground. The maintenance of such a big estate is prohibitively costly and so Lord Irwin sold it to the Leeds Municipality which manages it.

2nd OCTOBER 1955

There was a meeting to celebrate Gandhi-Jayanti and I was one of those scheduled to address it. About four Quakers and two Indians spoke. The Englishmen stressed the point that Gandhiji’s greatness was due to his following the principal tenets of Christianity. The tenour was that he became great by following Christian truths. The substance of what I spoke was that (1) in India tolerance of all religions is natural to the people, (2) I gave the instance of Ramakrishna who showed that every religion leads, if followed truly, to the same experience. In fact, religion is not a matter of profession or ceremonials; it should lead to experience. In everyone there is the divine Presence; in some it may be behind or hidden, in some others it may be on the surface. Mahatma Gandhi is a product of Indian culture. He himself declared more than once that he was “a Hindu of Hindus, a Muslim of Musalmans, a Christian of Christians”. He found whatever spiritual sustenance he wanted in the Gita. His life proves, to my mind, that it is not necessary to become a Christian in order to practise the highest truths of Christianity.

[1] When he knew that I would be leaving England he wrote to me the following letter:

Royal India Pakistan & Ceylon Society.

3 Victoria Street, London S.W.I.

26th Nov. 1955.

Dear Mr. Purani,

I think you may like to see the enclosed letter that I have received from the Institute of Indian Civilization in Paris. You will see that owing to a chapter of accidents they have not been able to carry out their original intention of inviting you to do them honour at a Reception.

Your visit to this country has been a great landmark for all who are interested in Indian Culture and particularly to the members of our society, who, thanks to Professor Langley’s book, already have some knowledge of Sri Aurobindo’s message. But I feel that before you leave on your return to India, we should meet to discuss the possibility of continued dissemination of this message which perhaps might be entrusted mainly to our Society.

Could we perhaps meet for a talk on Thursday, December 1st or the previous day, Nov. 30th about teatime? May I propose that this might be at your place?

With best wishes,

F. Richter

On 31st December 1955 he wrote:

I hope that you have had a pleasant voyage back to India. Those who were privileged to attend will always remember your stirring address about the great Teacher.

I have taken careful note of your suggestions to the Society and have also written to your friends in Arica regarding the purchase of copies of Langley’s book.

yours sincerely,

F. Richter

*

MANCHESTER:

3rd October, 1955: First Visit to the House of William H. Drewett, Where Sri Aurobindo had stayed from 1879 to 1884.

In the register of St. Paul’s, Rev. Drewett’s name was mentioned. The only thing known was that he had been a Congregational priest. I went to the Reference Library, Manchester, and looked up old reports of the Congregational Church. From one of them it was found that he had been the priest of the Stockport Road Church. His address was 84 Shakespeare Street.

Then the question was: how long had Rev. Drewett been in Manchester? This was not known.

Referring to the old files of the Manchester Guardian I found that he had resigned his pastorage in March 1881; it was definitely established that he had not been working in Manchester in 1882.

In order to ascertain whether Rev. Drewett had worked as a priest in Australia — after his departure from England — as I had heard from Sri Aurobindo — I went through the reports of the Australian Church from 1882; but did not find his name there.

Inquiring at the Municipal Office whether any changes had taken place in Shakespeare Street since 1880, I found no definite information. I started for the place myself in the evening and found that Nelson Street is in a line with the Royal Infirmary. Nelson Street becomes Shakespeare Street further on. House No. 84 was in a dilapidated condition, the ground was all broken. Knocking for a long time at the door brought no response. The surrounding houses showed signs of poverty. House No 79 was near; it was a medical store and an old man was present there. I inquired how long he had been there. He said he had bought the house 36 years before, and told me that the street had not undergone any change during the interval. He also told me that before the First World War this locality had been inhabited by cultured men but now it was labour that had come in. I asked why the two houses No. 80 and 78 were not in existence. He said that they had been pulled down and the empty space could clearly indicate the site.

*

I found in B.B.C. Manchester that religion is a subject of their broadcasts; priests are regularly called on T.V. also. England spends a good sum on spreading religious ideas. There is arrangement for different denominations too, on the B.B.C. I wonder why India could not follow the example of England in this respect.

I tried to get the house No. 84 Shakespeare Street photographed, but with three photographers I failed to get any help. No one had any arrangement for taking photographs outdoors. I went to Bolton to try to get an Indian student’s help in this task; but there also I failed.

5th OCTOBER 1955

I saw the docks at Manchester, which are a triumph of man over Nature. They are about 35 miles from the sea! A small creek-like river is widened and dug to bring steamers to the docks which are surrounded by land all round. In all big cities of England even now damage due to German bombing can be seen. The Manchester Docks were hard hit.

9th NOVEMBER 1955 : SECOND VISIT

As I had not succeeded in taking the photo of house No. 84 Shakespeare Street during my first visit on 3rd October, I had to go to Manchester again for that purpose. Fortunately Willie Lovegrove drove me to Manchester from Hampton-in-Arden. It was arranged with the controller of B.B.C. Manchester, Mr. Cave-Brown-Cave, that I would meet a number of invited persons in his office at Piccadilly. I stayed at the Essex Hotel. I suggested to Mr. Miller, who was assistant to the Director, to try to contact a daily or a weekly paper to find out whether a photographer was available. Accordingly I was informed that a photographer would come to the hotel at 3.30. p.m.

Fortunately Shakespeare Street was only five minutes’ walk from the Essex Hotel. But it was raining and cloudy. The photographer had flashlight with him. Three photos were taken and they all came out well. At the very time a man who looked like a soldier came out of the house with a small girl. I asked him the name of the owner and took it down. Going to the place indicated I found that the rent was being collected by a firm of solicitors and the owner was even willing to sell it. I did not succeed in eliciting more information about Rev. Drewett nor about the owner of the house.

I met Dr. Cyril Bailey, the only living contemporary of Sri Aurobindo from St. Paul’s school, London, on 8th October 1955 at Wantage, Berkshire. He had been professor of philosophy at Balliol College, Oxford, from 1898-1926. And during the last war he was again at Oxford. He has been the governor of St. Paul’s school for the last 50 years. My appointment was in the afternoon. I reached his place ‘Mulberries’ at 3.30. p.m.

The house was small, simple and quiet. When I knocked, someone opened the door. After putting the overcoat in the ante-room I turned and saw a small, lean man, 84 years old, with an intelligent face welcoming me. I greeted him in Indian style with Namaskar.

He said : “I do not often go out at my age and I don’t see many persons. I have worked for many years at St. Paul’s. I have asked to be relieved. Perhaps this year I shall be free.”

I started about Sri Aurobindo, and showed him two photographs of his childhood. His eyes brightened; he said about one, “Yes, I can recognise him here, but in the other photograph he is not recognisable.”

I tried to put his mind 70 years back by referring to his days at St. Paul’s as a student. He described Dr. Walker, the high-master, which reminded me of the words of Chesterton : “Surrounded by the aroma of havanna leaf, a man with a deep sonorous voice, an impressive personality. He took very few classes. He used to take the youngest students and coach them in subjects in which they were weak.” This agreed with what Sri Aurobindo had told us. Dr. Bailey said, “Once he (Dr. Walker) was taking such a class and I had to do my Greek lesson. He used to pace up and down the room, sometimes stopping at a desk to explain something to a student. One day I heard from behind: ‘Do not steal the poet’s gold.’ I was puzzled as I was not stealing anything. A second time I heard the same sentence, then I understood that he wanted me to translate it into Greek.”

The topic of our talk changed. Now it was limitation of the human reason. Dr. Bailey said, “Even the animals have intelligence which works as instinct; but it is a form of knowledge — only there is no logic, no argument.”

I brought to his notice Sri Aurobindo’s Alipore jail experience, his place in the Indian political struggle, and his great philosophical and spiritual synthesis. He asked me about the Colloquium at Oxford. I told him of the philosophers and their preoccupation with “Analysis” and “Reconstruction”. He was not happy about it.

He said that he had been more familiar with Monomohan Ghose than with Sri Aurobindo at St. Paul’s. “The age between 13 and 18 is such that boys hardly want to know all the details about one another. They have no interest m them.” What he said was true; Sri Aurobindo was at St. Paul’s, he was a scholar and took prizes and won a scholarship to King’s College, Cambridge, from St. Paul’s and yet Cyril Bailey, his contemporary, did not know it. He showed me round his house, a solid structure without upstairs, with a fine lawn and some apple trees. The water for use was heated by fuel stored up in a reservoir and used during day to wash hands, clean utensils, etc. Electricity was there but no water-pipe, no drainage. A small nursery garden with glass doors was also there. Mrs. Bailey came at 5 p.m. and joined us at tea and brought out a home-made cake which really was very tasty. She had gone to join the prayer for the harvest and the folk songs that are sung on the occasion. Both seemed to be interested in this aspect of collective life of Christianity.

Dr. Bailey showed an inclination n to read Diwaker’s Maha Yogi, his life of Sri Aurobindo. I sent him the book from London. He did not appreciate in it the hard strictures on the British Rule in India.

He wrote to me the following letter on receiving the book.

The Mulberries, East Hanney, Wantage, Berkshire,

26-10-1955

Dear Mr. Purani,

Many thanks for your letter and for procuring me a copy of ‘Maha Yogi’, which I am very glad to possess. I am reading it with interest. It tells me much that I did not know of Aurobindo, and, what is more, — it is the first time that I have read the history of that period and of the British occupation from the Indian point of view. I can understand and appreciate it and see how British actions and aims were interpreted often, I fear, rightly. But I think that the author does not do justice to the genuine love of many of the I.C.S. members for India and Indian friends. I do not think it was all “exploitation”. Aurobindo’s was a beautiful mind and educated. I wish I had known him better as a boy. I have an affection for Man Mohan which I wish could have included his brother.

Mrs. Balley asks me to send you her greetings. Accept also my own. Yours sincerely,

Cyril Bailey.

I wrote back :

5th November 1955

Dear Mr. Bailey,

I had to go to Durham and have come back only today.

Many thanks for your kind letter.

I agree with you about the one-sidedness or lopsidedness of judgment not only in this book but, I am afraid, in many other books written by young nationalist Indians. Perhaps it is excusable on the ground that freedom is a new experience to many of them. It takes time to realise the severe limitations even of national freedom and sovereignty. But I trust Indian Culture is old enough and ripe enough to outgrow this stage in a short time. We all expect an era of greater cultural interchange to pave the way for a really great human culture.

It is by stressing the points of human contact, which were far from being negligible and which have always existed in the past in spite of political differences and fights, that the two cultures and the two nations might be brought together to mutual advantage.

It is in this light that Sri Aurobindo is a very real link between England and India or more properly between Europe and Asia. The sweep of his mind is universal, his vision is comprehensive, free from prejudice or prepossession and, over and above all, he brings to all human problems an insight and detachment, a power of expression and logic which makes him rank among the creators of future humanity.

This may sound an exaggeration but I am giving expression not merely to my feeling and attitude but to a conviction based on what studies I have been able to make. I hope to send two of his books, The Human Cycle and The Ideal of Human Unity — both bearing on problems of social reconstruction and politicalunification of mankind which I am sure you will enjoy.

Please give my respects to Mrs. Bailey.

Yours sincerely,

A. B. Purani.

Dr. Bailey wrote to Mr. Cohen :

December 9, 1955

I shall certainly hope to listen to Sri Purani’s talk on Monday 19th. I am sorry that I shall not now meet him again, but am very glad to realise what a much greater man Sri Aurobindo was than I had realised. I have been reading the life with interest. I think that kind of mysticism does not come easily to the English mind, but it certainly gave me a great sense of respect and admiration.

Yours sincerely,

Cyril Bailey.

Dr. Bailey’s admission about want of capacity to understand ‘mysticism’ is not about himself but about the English mentality in general. It is due to the difference in the cultural heritage not only of England but of Europe. The inclination to practise Yoga does not come naturally to the English mind. Looking to the practical and even utilitarian values of the culture, and the long history of its economic, political and rational development, it seems natural that it should be so.

The last letter from Dr. Bailey was received by Alan Cohen who had informed him of the formation of a study-circle in London.

January 6, 1956

I am interested to hear of the group in this country which follows the Yoga of Sri Aurobindo. But I fear it is not for me; for one thing, I am too old in my 85th year, but more important, I am a convinced Christian and find it is more than I can do to make myself what I should be. I therefore regard Yoga with sympathetic interest, but not with more — it is too mystic for me. Yours sincerely

Cyril Bailey.

I have purposely given these quotations as they shed light on the attitude of educated Englishmen to spirituality. The reasons for the attitude also become clear:

The Christian religion as practised in Europe does not lead to any concrete spiritual experience except, perhaps, for a small minority m the Roman Catholic church. Yoga, or any system of psychological discipline that is consciously practised, does not easily appeal to the English mind, and this is understandable. It thinks: Why not choose one of the intellectual or ethical ideals which mankind has found in the past and follow it in life ? After all, man has to practise his religion with his ordinary nature; the essence of religion is the observance of all its injunctions and ceremonials, not concrete inner experience of the Reality. Such an attitude may admit some element of faith, devotion and even mysticism but it is a concession to human weakness. Hardly any Christian in Europe imagines it possible to go beyond the practice of ethical ideals as represented in Christianity. Of course, one great truth which most of the “convinced Christians” try to practise is the ideal of universal love based on brotherhood of man; they devote themselves to altruistic works, to service, to charity. That the pursuit of religion should end in an experience and possibly a change of consciousness is not acceptable to them.

The interpretation of the utterance of Christ, “I and my Father are one”, as the identity of the human soul with the essential Divine is easy for the Indian mind to understand. But the Christians seem to have narrowed it down to mean identity of Christ, the man, with the Divine. It is perhaps a legacy of the idea of an extracosmic God from a Jewish origin. The other great teaching, “Love thy neighbour as thyself”, has evidently a spiritual background of identity of self in all. But it has hardly been followed in practice by Christians. European nations for years have respected that great tenet in the breach and non-Christian nations have been victims of economic and political exploitation wherein either the flag followed the church or the church followed the flag. Conversion has been the main motive. After the renaissance the age of reason and science dawned in Europe. The one great truth which science has established is the unity of Matter or of Material Energy. The scientific mind of today, or the modem mind in general, accepts untold possibilities of Matter or Energy. But it is not prepared to grant unlimited potentialities of life-energy or of mind or of the spirit. Such an acceptance smacks to it of mysticism, superstition, woolly-headedness, traditionalism, etc.

Even when unconnected with politics the highest practice of Christianity ends in conversions of willing persons, in acts of service, spread of education and such other altruistic activities. In the modem world it is difficult to prevent the reasoning intellect encroaching on the field of religion and spirituality. The Roman Catholic religion relied on devotion and faith as its strong supports. But with the rise of Protestantism and other sects those living fountains of spiritual life — faith and devotion — were lost and the pure intellect did not get a place in religion. When scientific progress had its impact on the economic and political life of Europe the whole cultural trend became extravert, utilitarian, practical. With the establishment of Empires and Colonies the Western nations seem to have been convinced of their culture being the highest and the greatest that man has attained, and the other nations on earth also accepted the values of that culture because nothing succeeds like success. In the attitude of “convinced Christians” like Dr. Cyril Bailey there is tacit acceptance of the cultural values of Europe of the 17th century as the highest possible. I feel sure that sooner or later European culture will have to change that attitude.

*

B.B.C. TALK

One of the most important things I had to do in England was to make a broadcast on Sri Aurobindo in London in the Third Programme of the B.B.C. The Third Programme is intended for the intellectuals in England. The B.B.C., though an independent organisation, follows closely the policy of the government. So in their work England comes first, and then the continental countries including Russia and the United States. Asia and Africa are generally left to the overseas broadcasts.

Ever since I reached England I had been trying to meet the Director of the B.B.C. Being new to the town I went to the B.B.C. and met the Director of the Overseas Broadcasts, who was very sympathetic. From him I learnt that the Third Programme was under a separate department whose office was close by. Inquiring on the phone I learnt that the Director was out in Switzerland and would come after two or three weeks. I had a lot of other work to do and I had to be travelling out of London constantly. Whenever I was in London I tried to fix up an appointment. The secretary and his assistant wanted to find out my purpose. But I had decided to meet the Director and no one else. I felt it better to risk even a negative reply from the top rather than from subordinates. So the appointment with the Director took time. But in the meantime I had met the adviser to the Director at Oxford in the Colloquium.

At last on 13th October 1955 I got an appointment with the Director. I went with six or eight works of Sri Aurobindo’s in an attaché case on a cold morning to the office and was introduced to him. The adviser, whom I knew, was also present.

I began by stating that the relations between England and India after independence should be the beginning of an era of cultural exchange and co-operation. I added: “England stands to gain by such a process.” I then dwelt on Sri Aurobindo’s life in England and in India, his grand synthesis, ms two great epics — Savitri and Ilion. I suggested a broadcast on Sri Aurobindo in the Third Programme.

The Director listened; I then proceeded to show him the books I had taken with me. I noticed that he was not looking at the two books I had put on the table. I stopped showing the other books and sat down in my chair.

Then he asked me about the subject of The Life Divine. Having the opportunity I went on for more than 15 minutes in a non-stop attempt to achieve the feat of compressing 1100 pages into that tiny bit of time. He seemed impressed, I don’t know whether by the originality of approach or by the language or by both. He asked me about the other works. I spoke about Savtri and told him: “You don’t seem to realise the cultural tragedy involved in the fact that I, an Indian, have to come thousand miles to tell you that there is an epic in your language written by this great seer. As for his prose I would like to know how many writers can command that chaste style of his, maintaining throughout a height of thought. He has enriched the English language not only by literary works but by making current new words in it.”

He asked me: “Do you remember any such word?”

I : “Yes, I do. Can you tell me what the ‘bar dexter’ means?”

He tried for a minute — he was an M.A. of Cambridge — and acknowledged his ignorance.

I : “Do you know what the ‘bar sinister’ is?”

Of course, he knew the meaning. Then I explained to him that Sri Aurobindo had coined the term ‘bar dexter’ to mean a sign that indicates one’s claim to a higher birth, as ‘bar sinister’ indicates a mixture of lower strata of society in the family.

At last I said: “I am ready to lend these books to you; your assistant and the adviser can go through them and you may also read some work of his. If you find after reading that his books contain solutions of some of the basic problems of man-kind and the thought-content is original, then you may make a broadcast yourself. I am not keen on doing it myself. I have done that in India several times. But if on any account the broadcast is not done, I will not be sorry for Sri Aurobindo, I will be sorry for England.”

He said he would give the most sympathetic consideration to my request. Only, he wanted that I should meet him again. The day fixed was 22nd October. On that day I had to answer a barrage of some thirty questions prepared by the assistant and the adviser. I answered them all without any difficulty.

Then the conversation became light and the adviser, Gregory, told me : “Do you know why the Director asked you questions about Sri Aurobindo at King’s College?” I said : “No.” Gregory: “Because he himself is from King’s.” I got up and extending my hand said : “Shake hands — all great men from Sri Aurobindo to John Morris came from King’s.” Director : “You should have been in the Diplomatic Service.” Pointing to the adviser he said : “Do you know he was born in India?” I : “No.” I turned to Gregory : “Now, you have been keeping a secret. Where were you born in India?” He said : “In Benaras — my father was a missionary.”

I : “You should be holy, Gregory, it is a holy city.”

Then the Director said : “It is all right, you are the best fitted to prepare the broadcast we will give you the full time, twenty minutes.”

I spent anxious hours at night — for that was the only time free from all engagements. To condense Sri Aurobindo and his work into a text of about three thousand words and within twenty minutes seemed impossible and even absurd. Besides, the broadcast was for the British people whose cultural background is so different from that of India. But I was not alone, I was helped by His Light. I prepared the text in two or three days working overnight. The day of reading the text was fixed. I consulted the adviser, Mr. Gregory, who had become friendly with me. In my text I had quoted a passage from Savitri at the end. He was frank; he said: “It is your broadcast, you are free to keep the passage from Savitri if you like. But if you ask me, knowing the British public as I do, I would not end the broadcast with that passage.”

That day I sat overnight and changed the ending, and practised reading my piece aloud within twenty minutes. It is an important thing because generally one is too slow or too fast. At last the reading was done on the 16th of November. My greatest delight was that it sounded very well and it ended exactly on the 60th second of the 20th minute!

Gregory who was present shook hands with me and congratulated me, saying: “This happens very rarely, either it is 18 minutes or 22 when we have to cut off at 20.” I replied: “In His Work things happen like that.”

*

THE INDIAN INSTITUTE OF CULTURE :

62 QUEEN’S GARDEN, W-T 21st OCTOBER 1955, 8.15 p.m.

We two — Alan Cohen and I — started earlier to reach Queen’s Garden in time; as the place was not known even to Alan who, I thought, was omniscient about London. Even a taxi cannot help as one has to guide the cabman. We started by the tube-train when it began to rain with a strong, cold wind. The trees in the park opposite shed their leaves by the basketfuls. We tried for 20 minutes to find the street; there was no sign of a ‘Queen’ or of a ‘Garden’ ! There was only myself drenched in rain and shivering but a firm Alan. At last we found the house; the secretary was surprised to find that even in such weather a lecturer could manage to come 15 minutes before time!

She led us into a warm room. After some time people came in, among whom were some literary and prominent persons like Mr. Richter. Miss Quigly, a good student and devotee of Sri Aurobindo, was in the chair.

I began by emphasising the unity of aim between the Institute of Culture and Sri Aurobindo. In his programme the unity of mankind and the establishment of peace figure prominently as a necessary condition for founding the Life Divine on earth. Such a goal can be realised only by a psychological change in man-not by economic or political or constitutional means.

I also dwelt upon my disappointment with the Oxford Colloquium and examined some basic ideas of Russell and Moore. I stated too that organised religions would not be able to help man to achieve those aims. An effort to reach behind Mind was necessary.

Dr. Kenneth Walker and Mr. Richter came to speak warmly to me at the end.

Miss Quigly was very happy.

Talking to the small group after the meeting it became late, 10.30 p.m. We had thought that there would be no problem of transportation in London. But the secretary found on phoning for a taxi that there was no chance of having one at that hour when it was raining and the wind was blowing. I was afraid that the last bus for Anerley would be gone. Miss Beswick was dwelling on the vagaries of the weather when I assured her that we would be all right in spite of it. She advised us to go to Paddington Station and take the train.

When we came out, London was like a desert; no one walking on the streets, the inhuman reflections of the electrical lamps falling on the dark road and motor cars or motor cycles rushing and spreading their bizzare lights on the same. At last by good luck we caught hold of a motor cyclist who was starting, and found our direction to Paddington Station. We managed to get a taxi there and drove to Queen’s Gate in the desperate hope of catching the last bus to Anerley. I got the last bus but that was not going to Anerley but to the stable at Stratham Com, halfway to my destination. Anyhow I took the chance and sent away the weary Alan.

The conductor was very much concerned when he knew that my destination was Anerley. How on earth could a man, past his 60th year, think of reaching it at 11.30 p.m. under a downpour of rain half the way? I tried to allay his anxiety by saying that if it came to the worst I could walk down to Anerley. Getting down at Stratham Com I found Clapham Station nearby and actually got a train, the last one, at 11.30 nearly, which reached me to the Crystal Palace at midnight. From there I walked to Anerley, which is not very far.

Next day Alan pleaded he was not well — there was solid reason for it! — and could not attend to work. Some grace saved me from any physical ailment after the wind and lecture and rain and knocking and I attended to my schedule as usual.

*

The following letter was received from Miss Beswick, Secretary of the Indian Institute of Culture.

The Indian Institute of Culture

62 Queen’s Garden, W-2.

28-10-1955

Dear Sri Purani,

A week has gone by since you spoke here but very often during the days I have thought of your talk. We were all so very interested and helped.

One thing struck me very forcibly: we so complain over here of the weather, and Friday night was an awful night! Yet, linking up with your mention of Nature during your talk, I was struck by your full acceptance of the wet and the cold when you were leaving. It seemed a perfect example of making oneself “one with Nature” and enjoying her in one of her difficult moods apparently difficult!

So, for the talk, and the practical example, I do for myself and the branch thank you very much indeed. With my sincere wishes.

Yours—

Ethel Beswick (Secretary.)

Miss Pauline Quigly who had presided wrote the following letter:

Allencote, Limpsfield

Surrey,

25.10.1955.

Dear Sri Purani,

…It has been a great pleasure to read “Sri Aurobindo’s Message to Philosophy” and to have heard your address the other evening at the Indian Institute of Culture. It is a great occasion, since I began my studies of Sri Aurobindo five years ago, there has been rarely an opportunity of hearing the Message expounded. To have been in the chair on that occasion, was indeed a privilege and I was encouraged to find that my reasonings and interpretation of Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy, acquired only through reading, were in accord with the interpretation of one of the Master’s own disciples.

Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy seems to offer the one reasonable, scientific and spiritual solution to mankind’s manifold problems….

yours sincerely,

E. Pauline Quigly.

DURHAM. OCTOBER 30th TO 4th NOVEMBER 1955

From King’s Cross Station, London, to Durham the journey is from 12-15 to 6-00 p.m.

The train was late, so I reached at 7. Prof. A. Basu was on the station; we went to his recently purchased house, “Lydstep”, between England and Scotland. It is on a height. It has a fort where all things — the chief’s place, the under-ground cellars, arms — were so similar to those in the Rajputana Forts in India! Warwick Castle which I saw is also similar, it gives sheer on the river, the fort wall at places is five to seven feet wide.

During my stay I met Sir James Duff, Warden of the Oriental Faculty, whom I had met as a member of the University Commission in India. I also met Dr. Clifford, Professor of English, and had a long talk on English poetry. Sri Aurobmdo’s poetry figured in it. I gave him a copy of Sri Aurobindo’s essay, On Quantitative Metre.

I also met Mr. Randolph Quirk, Professor of English in Hatfield College, and Mr. D. E. Webster who works in the College of Physical Culture. There emerged in our talk a complete identity of views with regard to the need of a spirituality divorced from current religions, of practical steps for uplifting the consciousness of man. They were tired of the dry and monotonous sermons in the churches. It is true that there is a good percentage of men in Europe who want a rational spiritual viewpoint advocating voluntary practice of psychological methods divorced from outer ceremonials and rituals.

I also met Mr. Arthur Yeuchinson, Professor of Music, who had once come to Pondicherry. He had taken many records of Indian music with him to Durham.

Incidentally, on the 4th of November there was a dance recital by Ramgopal at Newcastle-on-Tyne, which was not very far from Durham. There are some Indians in Newcastle. The performance was rather ordinary, but for an English audience it was all right. I took the train at night from Newcastle and reached London in the morning.

*

7th NOVEMBER 1955 : VISIT TO HAMPTON-IN-ARDEN

Starting from London at 9 in the morning I reached Coventry at 11 o’clock. Willie and John Lovegrove, brothers of my friend Mrs. Pinto (Mona) came to the station but we missed each other. I crossed the bridge and was on the point of engaging a taxi when I learnt that a train for Hampton-in-Arden would be soon coming. It was raining. As I crossed the bridge again, both Willie and John met me, and we went in a car to the house of Mr. James Wood, their brother-in-law. Coventry town was practically razed to the ground by German bombardment. It is now rebuilt on a new sight. Hampton-in-Arden is a very pretty place in the central part of England. With Willie I saw a drama in Birmingham theatre and we had a long chat with the Wood family round the ‘hearth’. One could feel how true is the identification of the ‘hearth’ with ‘home’: it is before the heat-giving hearth that the family assembles in the cold of England.

8th NOVEMBER 1955

We saw Warwick Castle. On our way we had a look at Kenilworth Castle in ruins. It is said that a fort in the Mysore state in India is built in imitation of this castle and it is still in good condition there. We visited Leechfield Cathedral on our way. This was one of the Cathedrals destroyed by Cromwell. But the Catholics have built it again on the old foundations. Very fine brass work is to be seen in it. It has tombs of many famous persons.

Exactly at 9-30 a.m., the notified time, the window of the office opened to issue tickets for admission to Warwick Castle. A guide accompanied the company. There was a large collection of old arms and armours worn by soldiers, presents from Kings, old utensils. There was a very big vessel for cooking for hundreds of men with a recipe. The presents given to the Earl of Warwick by Queen Anne were housed in a separate room. Small and big size paintings were also preserved.

There was also a haunted room! Murders used to be committed m aristocratic and royal families in England as in India m the middle ages. Some prince of the Warwick family was murdered in the game of power. It is said that his spirit has haunted the room ever since. It may be true that the English do not believe in haunting spirits, and that they regard the belief as a superstition. But I saw a young woman hurriedly withdraw from the room followed by her husband. Such estates are costly to maintain; hence their use as museums for visitors.

12th NOVEMBER 1955

I was in London. Doris and I decided to pay a visit to the Golders Green cemetery in memory of Peter (Crampton-Chalk). Doris told me that he had decided for cremation. The distance from Kensington to the cemetery is long and I utilised it to talk to Doris about the sadhak’s attitude towards work. Doing action — Karma — is not doing Karma Yoga. The technique of Karma Yoga is clearly given in the Gita.

We bought some flowers at Golders Green. There the arrangement for the disposal of dead bodies is very neat — in a few minutes the powerful electric current reduces the body to a small quantity of ash. The ashes are then scattered on the green plot behind — the idea being to keep the memory of the departed ‘green’. We offered some flowers in his name; our hearts were filled with his memory and his presence. I said to him in silence: “We are trying to carry out the work which was so clear to your heart; and we know that your subtle help is there. I know that your future is safe under the protection of the Mother. A great vision of Truth brought us together and we are all one in the attempt to bring it into life. May you feel happy in the work that is done in England and may your progress to the Truth be unhampered.”

We returned full of emotion.

1st AND 2nd DECEMBER 1955

VISIT TO SRI RAMAKRISHNA MISSION, 68 DUKES AVENUE, MUSWELL HILL, LONDON

I and Alan went to the Mission in the afternoon, taking our lunch at a restaurant on Muswell Hill. We met Swami Ghanananda who had come from Madras. A clean-shaven young Englishman was his secretary. A disciple took me to the room where a large photograph of Sri Ramakrishna was kept. It had a very peaceful spiritual atmosphere. Swami Ghanananda proposed that I should speak to his group on the 2nd of December in King James’ Hall. As the proposal came from him I accepted it, having no other engagement on the date as I was leaving England on the 3rd of December.

At the meeting while introducing me, Swamiji made glaring errors in his reference to Sri Aurobindo’s life, for which I was sorry as I had to correct them before I began the subject proper : “The Gita in Sri Aurobindo’s Light.” I dwelt upon the difference between the Gita and other scriptures of India —its origin in a life-situation and its emphasis on “action” as a means of Yoga. The Gita is not other-worldly in its spiritual teaching, it shows the working of a Divine Will even behind the ordinary actions of individual and collective life.

LETTERS

27th March 1954

To Mr. S. C. Bach. (Oxford)

I feel that I may find friends who will render me assistance in establishing cultural contacts at the highest level-the universities, literary associations, poetical associations, philosophic circles, religious students. I want to present the new approach, the new thought, the new literary contribution, the new solutions which Sri Aurobindo has worked out. I want to present them rationally. The result I expect is awakening of interest in Sri Aurobindo, a kind of cultural fermentation so that his philosophic, literary and poetic contribution to the English language is at last recognised. I want him to be known among the intellectuals of Britain. More than this if I can achieve I shall be thankful to God.

A. B. Purani

*

10th December 1954

To Mr. S. C. Bach. (Oxford)

Let me tell you frankly that I am not interested in a visit to England for its own sake. Nor is it my purpose to do propaganda. Sri Aurobindo never wanted to start a religion or a sect. His contribution is of the highest cultural value to humanity to-day. It is my intention to evoke interest in the work of one who has contributed so richly to the English language and literature. It is a tragedy that Sri Aurobindo who was brought up in England from his seventh year and had a brilliant academic career at Cambridge should have remained practically unknown to the public and even to the intellectuals in England. His poetical and philosophical contributions alone are of such a value that they should be brought to the notice of the intellectuals.

A. B. Purani

*

14-9-1955

FROM THE VICE CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY.

The Master’s Lodge, Magdalene College,

Cambridge (Tel. 58058)

Dr. A.B. Purani,

31 Queens Gate Terrace, London, S.W.7.

Dear Dr. Purani,

Thank you for your exceedingly kind letter. I am so glad that you had a satisfactory talk with Mr. Saltmarsh.

I so much enjoyed our talk and was delighted that you met my grandchildren. I am writing today to Prof. Basu Willey, our professor of English literature, telling him of our talk, your contact with Mrs. Van Lohuizen, and of your hopes.

With every good wish,

Yours sincerely,

Henry Willink

*

I have had a ring from the Secretary of the High Master of St. Paul’s School. I am told that they have been searching through their records and can find no trace of attendance of Sri Aurobindo at the School, and wondered whether it might be that there is some confusion as to the school which he did in fact attend during the years 1884-1890. In view of thus the Hugh Master wondered whether you would still be interested in going to see him at 2-30 p.m. on the afternoon of Monday 26th September.

MARGARET HERBERTSON,

British Council.

*

I feel that your mission in this country was of inestimable value to the people of this land and may God grant you many more years in his “Vineyard”.

H. Bagnall Goodwin.

c/o British College of Naturopathy,

London N.W.3.

*

46, Great Russell St. W.C.I.

7.10.1955

It is indeed unfortunate that our stocks of Sri Aurobindo’s works are almost depleted. This is no doubt due to the result of your lectures in this country.

H. Raymond Luzac & Co.

*

25.10.1955

It has given me great pleasure to read ‘Sri Aurobindo’s Message to Philosophy’ and to have heard your address, the other evening, at the Indian Institute of Culture.

Pauline Quigly.

*

Your expression: “Here is an alchemist who has brought for mankind the ‘Divine Elixir of Life’” especially interested me : not before have I seen it used.

Pauline Quigly.

*

The University,

Leeds, 2.

9th November 1955

Dear Mr. Purani,

I have placed in our Brotherhood library your generous gift of the works of Sri Aurobindo and your own valuable interpretative studies. Members of the University will be glad to find so rich a representation of the wisdom and spiritual experience of this great man, who combined with the traditional philosophy of the Upanishads something of the personal and social dynamism of European though, who was a poet and creative writer in the English language and at the same time a liberator of the Indian people, who believed like Plato that education should lead to a direct vision of the Truth and that vision is necessary for salvation in private and public affairs.

We in the universities of this country will watch with the greatest interest the work of the University Centre in Pondicherry, which aims at realising for the benefit of students from all countries the educational aims of Sri Aurobindo, and your gift will often send us to the source of inspiration.

Yours sincerely,

Charles R. Morris.

*

A.B. Purani, Esq.

The Aurobindo International University Centre.

The Ashram,

Pondicherry,

India.

144 Grangewood St. East Ham., London, E.6.

14.11.1955

After I left you, I walked for a little while in Kensington Gardens and the green spaces there and the trees appeared like the top of a mountain! — This morning the few leaves left on the trees shone like jewels and the very gulls over the lake were winged messengers.

Clare Cameron.

*

30 Kimberly Road, Cambridge.

28.11.1955

It was an exceeding joy and help to all of us gathered at the meeting to hear your very impressive, profound and inspiring address. All present thoroughly enjoyed and appreciated it.

Here is the Mother telling about Purani, in one of her related conversations, Agenda dated 22 January 1966:

All sense of compulsion, of necessity (and even more of fate) had com-plete-ly vanished. All the illnesses, all the events, all the dramas, all of it—vanished. And this concrete and so stark a reality of physical life—completely gone.

The interesting point is that the experience arose from my encounter with Purani last night. I met Purani in a certain world and he was in a certain state, like the one I have just described, but then the difference between Purani as he was here and Purani as he is now… suddenly, it was like a key. I spoke to him, he spoke to me, saying, “Oh, now I am so happy, so happy!” And it was in that state that I lived this morning for more than an hour and a half. Afterwards, I am obliged to come back… to a state I find artificial, but which can’t be helped because of others, the contact with others and things and the innumerable amount of things to be done. But still, the experience remains in the background. And you are left with a sort of amused smile at all the complications of life—the state in which people are is the result of a choice, and individually the freedom of choice is there, but they have FORGOTTEN it. That’s what is so interesting!

…

I remember, last night when I stretched out on my bed, there was in the body an aspiration for Harmony, for Light, for a sort of smiling peace; the body aspired above all for harmony because of all those things that grate and scrape. And the experience was probably the result of that aspiration: I went there and met a pink and light-blue Purani (!)—what a blue! The pretty, very pretty light blue of Sri Aurobindo.

A.B. Purani recalls his first meeting with Sri Aurobindo at Pondicherry in his book ‘The Life of Sri Aurobindo’, pp. 292-296:

‘…though I had seen him from a distance and felt an unaccountable familiarity with him, still I had not yet met him personally. When the question arose of putting into execution the revolutionary plan, which Sri Aurobindo had given to my brother – C. B. Purani – at Baroda in 1907, I thought it better to obtain Sri Aurobindo’s consent. Barin, his brother, had given the formula for preparing bombs to my brother, and I was also very impatient to begin the work. But still we thought it necessary to consult the great leader who had given us the inspiration, as the lives of many young men were involved in the plan.

I had an introduction to Sj. V. V. S. Aiyar who was then staying at Pondicherry. It was in December 1918 that I reached Pondicherry. I did not stay long with Mr. Aiyar. I took up my bundle of books – mainly the Arya – and went to No. 41 Rue Francois Martin, the Arya office, which was also Sri Aurobindo residence. The house looked a little queer, – on the right side, as one entered, were a few plantain trees and by their side a heap of broken tiles. On the left, at the edge of the open courtyard, four doors giving entrance to four rooms were seen. The verandah outside was wide. It was about 8 in the morning. The time for meeting Sri Aurobindo was fixed at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. I waited all the time in the house, occasionally chatting with the two inmates who were there.

When I went up to meet him, Sri Aurobindo was sitting in a wooden chair behind a small table covered with an indigo-blue cloth in the verandah upstairs when I went up to meet him. I felt a spiritual light surrounding his face. His look was penetrating. He had known me by my correspondence. I reminded him about my brother having met him at Baroda; he had not forgotten him. Then I informed him that our group was now ready to start revolutionary activity. It had taken us about eleven years to get organised.

Sri Aurobindo remained silent for some time. Then he put me questions about my sadhana – spiritual practice. I described my efforts and added : “Sadhana is all right, but it is difficult to concentrate on it so long as India is not free.”

“Perhaps it may not be necessary to resort to revolutionary activity to free India,” he said.

“But without that how is the British Government to go from India?” I asked him.

“That is another question; but if India can be free without revolutionary activity, why should you execute the plan? It is better to concentrate on yoga – the spiritual practice, he replied.

“But India is a land that has sadhana in its blood. When India is free, I believe, thousands will devote themselves to yoga. But in the world of today who will listen to the truth from, or spirituality of, slaves?” I asked him.

He replied : “India has already decided to win freedom and so there will certainly be found leaders and men to work for that goal. But all are not called to yoga. So when you have the call, is it not better to concentrate upon it? If you want to carry out the revolutionary programme you are free to do it, but I cannot give my consent to it.”

“But it was you who gave us the inspiration and the start for revolutionary activity. Why do you now refuse to give your consent to its execution?” I asked.

“Because I have done the work and I know its difficulties. Young men come forward to join the movement, driven by idealism and enthusiasm. But these elements do not last long. It becomes very difficult to observe and extract discipline. Small groups begin to form within the organisation, rivalries grow between groups and even between individuals. There is competition for leadership. The agents of the Government generally manage to join these organisations from the very beginning. And so the organisations are unable to .act effectively. Sometimes they sink so low as to quarrel even for money,” he said calmly.

But even supposing that I grant sadhana to be of greater importance, and even intellectually understand that I should concentrate upon it, – my difficulty is that I feel intensely that I must do something for the freedom of India. I have been unable to sleep soundly for the last two years and a half. I can remain quiet if I make a very strong effort. But the concentration of my whole being turns towards India’s freedom. It is difficult for me to sleep till that is secured”.

Sri Aurobindo remained silent for two or three minutes. It was a long pause. Then he said: “Suppose an assurance is given to you that India will be free?”

“Who can give such an assurance?” I could feel the echo of doubt and challenge in my own question.

Again he remained silent for three or four minutes then he looked at me and added “Suppose I give you the assurance?”

I paused for a moment, considered the question with myself and said: “If you give the assurance. I can accept it.”

“Then I give you the assurance that India will be free, he said in a serious tone.

My work was over – the purpose of my visit to Pondicherry was served. My personal question and the problem of our group was solved! I then conveyed to him the message of Sj. K. G. Deshpande from Baroda. I told him that financial help could be arranged from Baroda, if necessary, to which he replied, “At present what is required comes from Bengal, especially from Chandernagore. So there is no need.”

When the talk turned to Prof. D. L. Purohit of Baroda Sri Aurobindo recounted the incident of his visit to Pondicherry where he had come to inquire into the relation between the Church and the State. He had paid a courtesy call on Sri Aurobindo as he had known him at Baroda. This had resulted in his resignation from Baroda State service on account of the pressure of the British Residency. I conveyed to Sri Aurobindo the good news that after his resignation Mr. Purohit had started practice as a lawyer and had been quite successful, earning more than the pay he had been getting as a professor.

It was time for me to leave. The question of Indian freedom again arose in my mind, and at the time of taking leave, after I had got up to depart, I could not repress the question – it was a question of very life for me : “Are you quite sure that India will be free?”

I did not, at that time, realise the full import of my query. I wanted a guarantee, and though the assurance had been given my doubts had not completely disappeared.

Sri Aurobindo became very serious. The yogi in him came forward; his gaze was fixed at the sky that could be seen beyond the window. Then he looked at me and putting his fist on the table he said :

“You can take it from me, it is as certain as the rising of the sun tomorrow. The decree has already gone forth; it may not be long in coming.

I bowed down to him. That day I was able to sleep soundly in the train after more than two years. And in my mind was fixed for ever the picture of that scene : two of us standing near the small table, my earnest question, that upward gaze, and that quiet and firm voice with power in it to shake the world, that firm fist planted on the table, – the symbol of self-confidence of the divine Truth. There may be rank Kaliyuga, the Iron Age, in the whole world but it is the great good fortune of India that she has sons who know the Truth and have the unshakable faith in it, and can risk their lives for its sake. In this significant fact is contained the divine destiny of India and of the world.

After meeting Sri Aurobindo I was quite relieved of the great strain that was upon me. I felt that Indian freedom was a certainty, I could participate in public movements with equanimity and with a truer spiritual attitude. I got some experiences also which confirmed my faith in Sri Aurobindo’s path. I got the confident faith in a divine Power that is beyond time and space and that can and does work in the world. I came to know that any man with a sincere aspiration for it can come in contact with that Power.

There were people who thought that Sri Aurobindo had retired from life, that he did not take any interest in the world and its affairs. These ideas never troubled me. On the contrary, I felt that his work was of tremendous significance for humanity and its future. In fact, the dynamic aspect of his spirituality, his insistence on life as a field for the manifestation of the Spirit, and his great synthesis added to the attraction I had already felt. To me he appeared as the spiritual Sun in modern times shedding his light on mankind from the height of his consciousness, and Pondicherry where he lived was a place of pilgrimage.’

About his second meeting with Sri Aurobindo which took place in 1921, Purani writes (in his ‘The Life of Sri Aurobindo’, pp. 296-297):

‘The second time I met Sri Aurobindo was in 1921, when there was a greater familiarity. Having, come for a short stay, I remained eleven days on Sri Aurobindo’s asking me to prolong my stay. During my journey from Madras to Pondicherry I was enchanted by the natural scenery – the vast stretches of green paddy fields. But Pondicherry as a city was lethargic, with a colonial atmosphere – an exhibition of the worst elements of European and Indian culture. The market was dirty and stinking and the people had no idea of sanitation. The sea-beach was made filthy by them. Smuggling was the main business.

But the greatest surprise of my visit in 1921 was the “darshan” of Sri Aurobindo. During the interval of two years his body had undergone a transformation which could only be described as miraculous. In 1918 the colour of the body was like that of an ordinary Bengali – rather dark – though there was lustre on the face and the gaze was penetrating. On going upstairs to see him (in the same house) I found his cheeks wore an apple pink colour and the whole body glowed with a soft creamy white light. So great and unexpected was the change that I could not help exclaiming:

“What has happened to you?”

Instead of giving a direct reply he parried the question, as I had grown a beard: “And what has happened to you?”

But afterwards in the course of talk he explained to me that when the Higher Consciousness, descends from the mental level to the vital and even below the vital, then a transformation takes place in the nervous and even in the physical being. He asked me to join the meditation in the afternoon and also the evening sittings.’…

‘On the last day of my stay of eleven days I met Sri Aurobindo between three and four in the afternoon. The main topic was sadhana.

When I got up to take leave of him I asked him:

“What are you waiting for?” I put the question be¬cause it was clear to me that he had been constantly living in the Higher Consciousness. “It is true,” he said, “that the Divine Consciousness has descended but it has not yet descended into the physical being. So long as that is not done the work cannot be said to be accomplished.”

I bowed down to him. When I got up to look at his face, I found he had already gone to the entrance of his room and, through the one door, I saw him turning his face towards me with a smile. I felt a great elation when I boarded the train: for, here was a guide who had already attained the Divine Consciousness, was conscious about it and yet whose detachment and discrimination were so perfect, whose sincerity so profound, that he knew what had still to be attained and could go on unobtrusively doing his hard work for mankind. External forms had a secondary place in his scale of values. In an effort so great is embodied some divine inspiration; to be called to such an ideal was itself the greatest good fortune.’ (Ibid., p. 298)

Here is an anecdote about Purani-ji. Once, Purani-ji was asked by someone whether he had seen the Himalayas. Purani-ji replied: “After having seen Sri Aurobindo I feel no need to see the Himalayas!”

Such was his reverence for Sri Aurobindo!

Amal Kiran writes about Purani-ji in one of his letters:

‘I remember my friend Purani telling me an incident of early days. Sri Aurobindo was standing at the door of his room while Purani was leaving. The disciple went down on his knees to make obeisance to Sri Aurobindo’s feet. After a few seconds he lifted his head and looked up. There was nobody standing any more. Purani told me with a laugh: “Strange Guru indeed who runs away like that!” (‘Life-Poetry-Yoga’, Volume II, p. 140)

In another letter, Amal Kiran recalls about Purani in a witty tone:

‘In the early days when I used to watch people meditate with the Mother rather than do meditation myself, I made a series of sketches of many of them and put short sentences below my pictures. I had seen Purani’s neck grow twice its normal width when he had plunged into meditation. Something from above his head appeared to be descending into him with tremendous weight, as it were, and his neck had to bulge out all round most spectacularly in order to hold the descent. Later I came to know that the descent could be like a bar of steel entering the head and sending one dizzy at first. My witticism below the little sketch of Purani ran: “Purani trying hard to swallow the Supermind.” (‘Life-Poetry-Yoga’, Volume II, pp.303-304.)

K. Amrita on Purani:

“The Mother has a huge vital body. Anything even distantly approaching it is the vital body of Purani.” (‘Life-Poetry-Yoga’, Volume III, p. 295)

Amal Kiran writes about Purani in one of his letters:

‘Purani was another sadhak with whom I was in close touch. Indeed, with the exception of Pujalal, he was the first Ashramite I met. Pujalal had taken us to his room which… had been Sri Aurobindo’s earlier. Purani was out. He was in the main Ashram-complex where—as I soon learned—his job at the time was to prepare hot water for the Mother’s early bath as well as to massage one of her legs which was not functioning in a fully normal way. I may mention in passing that for a long time Purani was to my wife and me the most impressive figure among the Ashram-members. In comparison to his energetic personality, both physically and psychologically, all the other Ashramites we met seemed rather colourless. I remember Nolini remarking after Purani’s death many years later that his personality had such force that he could have caught hold of anybody on the road and turned him to carry out what he willed. Nolini also used at that time the term “mahapurusha” (“great being”) for him. Purani had some occult powers and could go out in his super-forceful subtle body and act effectively. Once Vaun McPheeters, who with his wife Janet (renamed “Shantimayi” by the Mother) was the first American to settle in the Ashram, spoke a trifle lightly of India during a somewhat heated discussion with Purani. Purani, an arch-nationalist, could not stomach it. He told me that during the ensuing night he had found Vaun’s subtle form worrying him during sleep and he had gone out in his own subtle form and given Vaun a thrashing. Almost immediately there was a notable change in Vaun’s outer life. He went into retirement and was spiritually in a disturbed state. The Mother found her inner work on him getting difficult and did not know why until Purani narrated to her his encounter.

‘I may note here that though Purani’s relationship with Sri Aurobindo was very deep and intimate it was not always steady and secure with the Mother. After Sri Aurobindo’s departure he was often uneasy in the Ashram and once, when I happened to be in Bombay, wrote to me about feeling like leaving it. I earnestly advised him not to decide anything before having an interview with the Mother. He asked for an interview. During it, amidst other matters, the Mother said: “I am here only to do Sri Aurobindo’s work. Won’t you help me in it?” Purani burst into tears and pledged unfailing cooperation.’ (‘Life-Poetry-Yoga’, Volume III, pp. 295-296)

Nirodbaran writes about Purani in his well-known book, ‘Twelve Years With Sri Aurobindo’:

‘Purani was already known to Sri Aurobindo from the twenties and had enjoyed his closeness during those years. It was thus with him a resumption or the old relation after a lapse of many years. …