Dear Friends,

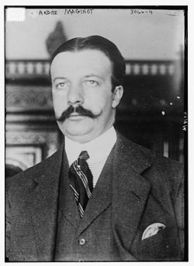

Maurice Magre (2 March 1877—11 December 1941) was a French poet, writer and dramatist. A staunch defender of Occitanie, he contributed significantly to make known the martyr of Cathares of the twelfth century. He was one of the most far-ranging and extravagant French writers of fiction in the first half of the 20th century, and perhaps the finest of them, because of the versatility of his imagination and the manner and purpose for which he deployed it. In the second part of his life, he became interested in esotericism. A seeker of spiritual light, he visited Pondicherry in 1935 to meet Sri Aurobindo.

This is the concluding part of the translation of the chapter “L’Ashram de Pondichéry” in Maurice Magre’s book ‘À la Poursuite de la Sagesse’ published by Fasquelle Éditeurs, Paris, 1936. The Mother is reported to have remarked that Magre’s impressions were shot with a psychic vision. Thus they have an inner value in addition to the purely historical. This article has been translated into English by K. D. Sethna alias Amal Kiran.

With warm regards,

Anurag Banerjee

Founder,

Overman Foundation.

_______________________

The Ashram at Pondicherry

Maurice Magre

In the order that reigns in the Ashram one feels admiration for the divine work. The work portioned out to each, the glances filled with quietude, the form of the shadow projected by the tree, everything proclaims obedience to law. Happy the one who can find the divine law beautiful, the law that since the aggregation of the first atoms has willed the triumph of the strongest. Sometimes I happen to say to myself: If I were God!

All my efforts would have consisted of contradicting the order of things. I would have given sap to the trees during the winter so that the fruits might appear under the snow and that it might make them fall by the bursting of their warm flesh. I would have given to the solitary man the surprise of finding a thin-bodied virgin in his empty bed. The servant would have seen his work ended before having begun it. To one who is avid of beauty I would have brought dreams so splendid that he would keep lying down until he died, for fear of interrupting them. According to my capacity as God I would have prevented man from degrading himself. A God cannot reform the world but He can help to better it by supernatural creations. Baseness comes from pride and it comes from misery. I would have lowered the pride of the powerful by peculiar miracles and they would be stripped of their dresses and their houses as the butterflies emerge from their chrysalises to become winged beings. I would have breathed into the heart of miserable creatures such a hunger for beauty that they would have laid aside their tools, their brushes, their sacks of coal to see how a flower blooms or what grace the clouds have when they stretch across the setting sun. I would have mastered the sexual energy which blinds the clear-sighted and makes four-footed those who before were standing on two feet. I would have castrated them and made them learn the inutility of reproducing themselves and of spreading upon the planet beings condemned to pluck bitterly their sustenance without ever thinking of their souls. I would have fixed myself to the earth in order to transform it so forcibly that I would have felt against me the palpitation of its substance; I would have clasped the hearts of men with a love so puissant that I would have moved them to a love equal to mine. O the mad dream of being God!

*

The Buddha teaches that we should escape from the wheel of lives and re-enter most swiftly the bosom of God and not occupy ourselves with the magnificent curve in which the creatures are put forth.

You contradict this ancient sage, this reformer of personal views. God, you say, has not organised with an infinite prevision the descent of life into matter, from the dull rock to conscious man, so that man may profit by this consciousness in order to escape from the law and return by a short cut to the primary source whence he started. It is thus the lamb does, hardly desirous of skipping in the sunlit hills; it returns, when the dog is inattentive and the shepherd sleeps, to the stable where it can dream at ease. But why is the lamb not right in preferring the prairie of its dreams to the hard rockpath where short grass grows and it bruises its delicate hooves? The work of God is immense and the curves He traces are of infinite variety. Certain comets trace limited ellipses around the suns whose satellites they are, while others lose themselves in the infinite without the astronomers being able to calculate their return. Are we not in the right to consider earthly evil and its visible aggravation even by our uncertain standards as the sign that we must retrace our steps?

The divine creation does not develop with surety. It resembles the work of an architect who makes attempts, builds and demolishes without any care for the materials he uses. There have been grotesque species, which had organs not adapted for living and which the Creator had given up sustaining. There have been over-prolific ones which exceeded His plans by their pullulations and which he had to destroy by means beyond natural laws. Why should not the human creation end in an impasse whose sorrow, injustice and falsehood would be the Mané, Thecal, Pharès, warning the souls that they must find in themselves the resource of their salvation?

“Evil is incomprehensible,” you reply, “for a human intelligence and one should be much farther and much higher in order to seize the necessity and the benefit.” But it is a strange paradox unworthy of God who has willed it. What is the better part of us, what is divine, revolts against this explanation. One cannot shut up a prisoner and make him suffer in the prison, telling him that these torments have an origin which has to remain incomprehensible to him and which he must bless in spite of this. Or if these torments have a cause to which he has himself given rise in previous lives, how should we judge a Creator who has taken away the memory of these causes and in consequence the possibility of modifying them, who has made man responsible for chastisement and unresponsible for redemption? “One has not the right to judge the Creator,” you will say. But why? Since He has willed that with the human reign there should appear a faculty of judgment. Unless this faculty has been born despite Him, unless He has been, at some minute of the cosmic ages, like one who sowing the wind reaps the whirlwind, like one who playing with fire forgets the power of his creation and lights in his own dwelling a flame which he cannot any more extinguish.

*

You have penetrated the wisdom of books and of traditions. You have made a tour of the sciences like Aristotle and of metaphysics like Shankara, and after having followed the immense circle of human knowledge you have leapt towards the supreme essence of the spirit like a jet of water that is urged by a formidable hidden pressure and carries in itself the spirit of solar rays. You have crossed the invisible world of illusions as a dauntless swimmer crosses a gulf full of monsters, dispersing them with his breath. And now you are stripped of fear, enveloped in calm, concealed in serenity. You keep yourself in the midst of your disciples’ love like a unique rose around which the foreseeing gardener allows only delicate grasses to grow.

How could you deceive yourself, you who have touched the Divine, you who have gained the experience of what is above human reason? And yet I cannot prevent myself from remembering that the Buddha told his disciples to believe nothing beyond what they had understood with their own inner faculty, what was of the divine essence.

*

In the country from which I come, one does not worship the spirit. Hardly a few men, in the monasteries, practise methods analogous to yours by glorifying the prophet who was born in Judaea. I do not shave my head, as is their practice, I am not dressed in rough serge, I have not sung their canticles. I dreamt of a light for which the cloisters have too much shadow and the basilica too much sadness.

Once only in my childhood I grazed the mystery of solitude and of the Presence. It was not far from Toulouse, the town where I was born, in a country where all is sweetness and half-tint and where nature is like a child that has never been ill-treated by its father. On the bank of the Garonne where the poplars grow, there is a great house of stone. When I had run up to it, I stopped, seized by the silent beauty of the landscape. And suddenly I saw, emerging from a pathway, men clothed in robes and looking into themselves. They were walking gravely. They were going nowhere. They disappeared among the trees. A clock struck six. I have not been able to forget them.

The men whom I see here do not resemble them at all. They have more love for the sun and for living nature. I feel closer to them than to the others. And while I have seen them walking under the trees where there were so many singing birds, I have not been able to check myself from dreaming of those men of Toulouse who were passing under the poplars when the clock struck six and whose prophet had been crucified.

But towards these or towards those, I have gone too late or too early. It is one’s youth that one should offer to the Divine. Fortunate are those who rise at dawn and have reached the end of the course before sunset. When I crossed the threshold of the Ashram, there was a form which barred the way. It stretched out its arms and said: “Turn back your steps! It is too late!” And this form it was myself who created. In the gladness of arrival I had passed by it, seeming to ignore it, but it has pursued me step by step, it has kept by my side and always it has whispered in a low voice, with a great deal of melancholy: “Turn back your steps, it is too late!”

*

The men in rough serge, who walk under the poplars of Toulouse, have too melancholy songs. The organ has always moved me to despair. I am penetrated with the joy of life and cannot bear human injustice.

Torn by this contradiction, I am tossed between my admiration for the forms of earth and my revolt against their suffering. When I see the trees in cluster lifting harmoniously towards the sun, like chalices of sap and leaves, I wish to be only a branch and share in such a surge. When I see a stunted bush writhing among dry stones, straining towards an ungracious universe the anger of its thorns, I want to give it my blood if it can change it within its substance into a bit of fresh greenness.

But I am crushed by the immensity of law and I ask myself why I have been given this faculty of accepting it when I cannot modify it in the least? How to get out of these two opposed ideas that answer to each other like the sound and the echo, like the beatings of a clock, like day and night? Should one admire nature and hurl oneself gladly like a swimmer who follows the current of a river, letting himself be carried by the waters and getting drunk with the beauty of the banks? Or should one believe in the word of a host of saints who have rejected the temptation, revolted against Evil, prepared themselves their cross, loved better to be flayed alive than to bow before God?

O Master, if you know, resolve for me the problem, utter the liberating word, the word that makes the inner chains fall. If in the mysteries of Samadhi you have caught a glimpse of the truth, if you know why man is on the earth, what sense has the face of beauty, what sense has the grimace of grief, whether one should love them equally, say it and your word shall make the universe ring, it shall rejuvenate it to its foundations. For the truth is divine. There cannot be any calm for the disciple, even though he take ten million breaths attuned to the rhythm of the stars, if he knows not why creatures have been thrust upon the planet, to live there, to decompose there and be reborn.

*

O Master, it is not possible that there should be no redemption for a man of the West! I do not have the pride common to those of my race. It has been for a long time that I have regretted not having been born with a bronzed face, near a temple where I would have performed rites since my childhood and where I would have obtained naturally what I seek with so much pain. Out there, I am solitary in the midst of men. I do not understand them any more and I feel that they have ceased to love me because I am no longer like them. But here I am a stranger. The language and the dress create an insurmountable barrier. I should like to cry out my love for men and for things and I remain an indifferent personage who pronounces banal words. But this again is nothing. You have given me a welcome most magnificent. The room is very beautiful and the food very rich and the servant very zealous.

I have visited all the rooms of the Ashram and all the doors have been opened to the guest. But there is one invisible room which has neither door nor walls and which is the room of the Spirit. Within that, I have not been admitted. If I were worthy of entering it, there would be no need to demand and I would find myself there by the power of wishing. I know my unworthiness and I have gauged the distance which separates me from a goal of which I have not even a glimpse; but is there not an instruction which you give to some people? As one who reaches the summit of a high mountain throws a rope to those who are remaining in the valley, you should throw some marvellous words to fill the soul with happiness and allow it to raise itself.

O Master, make these words resound for me. I know that the voices which go from below can always be heard, thanks to the force which sound has, and that no prayer is lost. And I know that the voice from on high has a tendency to rise and is not perceived by the deaf who are houses below. I need a sublime order, an instruction which falls like a luminous stone, a teaching come from the summit. Tell me how the spiral of meditation should climb up, give me a formula of prayer, even a syllable to which I would cling like a swimmer who has found a buoy. I am one who is deaf and still wishes to hear, who is blind and yet opens wide the eyes. Make one sign from your side, a tiny bit of it can save me from despairing of salvation.

*

Perhaps I have understood the secret. He who has mounted cannot redescend, even if he wishes it with his heart of old times. He who has attained the house of wisdom cannot re-open the marble gate, even if there is someone who begs, on a stormy evening, in a desperate tone. Just as we do not bother ourselves whether the water of marshlands is vivifying enough to let tadpoles grow harmoniously into frogs, so too he who has access to divinity cannot soil his feet any more in the marshes of men.

I knock at the marble gate. Never has the night been so thick. Never has the wind blown with such tumult. Is it not already much to have discovered this gate across the shadow, even if one has to die by the perfection of its whiteness?

O Master, what is the sign by which to recognise the one who ought to enter, the one who is permitted to receive the transmission of the Spirit? Is he chosen by virtue of an incomprehensible grace or does he choose himself by the ardour of his faith and the purity of his love?

*

O Mother, while your hands of a Sheherazade are stretched in the half-light of the hall of elevations for the benediction of disciples, the invisible Presences stand by your side.

Then the souls mount in a group, disengaged from the body’s form, and by this grace that comes from you they have the faculty of uniting.

I have seen them, at the twilight hour, like a cloud of radiant beauty, rise towards the tranquil sky, lift high in a single sheaf, when the birds go to sleep, when the stars begin to appear.

As long as your hands are outstretched, like two symbols of adoration, the souls of all the disciples are united in love of the Master, they taste the beatitude and the perfection of love.

And when you sweetly lower your hands there is an invisible separation, the beautiful Egregore of the bluish gold fades and comes back to the earth, all the souls return to their earthly form, as the colours of a rainbow, after having shone in a circle, become again mist and azure.

*

O Mother, I have not risen with the chosen ones and the blessing has passed by me. But, in the measure of his sincerity, has not each the right to a little bit of love?

It is part of the attributes of your power to help the men who appeal to you at the beneficent hour of death. And this hour is like a cloud that sails round my sky without moving farther or disappearing.

O Mother, when this hour comes for me, may my breath have strength enough to pronounce the syllables of your name; may my memory be lively enough to build up your exact image within the shadows of remembrance!

May you keep by my side like a seraph of pity and dispel before me the ensnaring people of the shadows! May you lead me, stripped of fear and pride, towards the abode where the pure ones go, where all is love and beauty!

*

I shall depart loaded with a precious treasure. I have not gained the answer which I came to seek. But the great masters answer not to the questions of men. Jesus and Buddha kept silent and they have taught that it was vanity to know. Perhaps the supreme wisdom is to limit the vision to the span of what one sees. Perhaps there is even a higher wisdom which lies in not seeing.

On the most sacred soil of the world I have come to seek that which I name the Truth. I have beheld men good and pure and such as I did not know could exist. They have had merely to stand before me to attest by their presence that there is no wisdom superior to uprightness of heart. I am going a thousand times brimmed. I feel myself marked by an elective grace. I am like him who has gone to quest for gold and who brings back a stone precious like one that can only be in the planet Venus. It is because somewhere, in the dark world, there is this beauty of the soul, because some men have uplifted themselves silently towards perfection, that all men can be saved.

*

I have taken a handful of earth, a handful of the earth of India, to carry it for remembrance in my own country. I have looked at this earth in the hollow of my hands. It was exactly like the earth of a field of Toulouse, which I took when I was a child and which I ran between my fingers. All the earths resemble one another. All are made of the primitive substance and of the reuse of dead plants. But the spirit is different. What I should have carried was a little of the eternal light whose ray has descended here. I have come quite close to it. But the light of a divine order has this subtle quality of passing without leaving a trace. Has it perhaps touched me? How shall I know, my God? Oh if I have carried merely this handful of earth in the hollow of my hand, this handful of Indian earth so like the earth of other countries!

*

I was going to leave and someone carried my baggages across the rooms and along the staircase. I saw a man who was naked with a loin-cloth. He prudently kept apart and lowered his eyes while joining his palms all the time my look met his. There was under these traits a strange joy and the illumination of perfect beings. I thought of some saint come at the last hour for a marvellous communication.

“What is this man?” I asked with an inner emotion the servant who acted as my interpreter, “and what does he want?”

The servant answered: “He has come to know that you are leaving for France and he wishes to get a bit of money on this occasion.”

I kept silent and then my soul was filled with joy. If the face of the beggar and that of the saint wear the same beauty it is because to give and to receive are two actions of the same essence, which only seem different to eyes that do not know how to see.

O Master! through the intermediary of one who asked me for an offering, your message has reached me!

*

O Master, you have not cured the leper, you have not delivered the woman possessed nor ostensibly walked on the waters. By the path you have discovered in the inner labyrinth of the spirit, you have reached the realm of the Divine. No Lazarus has risen from the tomb to bear witness to your power, no miracle has flashed forth like a celestial aerolite. But a few inspired men have known that the miracle has taken place in silence and solitude and they have come to gather around you. With the souls of these perfect ones you have condensed a spiritual diamond of such purity that the earth has not known its like. What pride would be required of me to believe that I could mingle with these perfect ones or rather what ignorance would be required! Now my soul will turn back eternally to the place of election where you live and each night it will perch on the trees of the Ashram, lost in the thousands of birds that sleep with folded wings and fly off at dawn.

*

These are words which one uses and whose sense one understands only very late. One pronounces them a thousand times without knowing their value. And all of a sudden these vague words become alive in front of you, as if they had blood in their letters and flesh in their syllables.

Ah! how poignant they are and nostalgic, charged with all the distress of my soul, these words which have remained up to now mute and lack-lustre, these words which have just revealed themselves to me in their profundity of despair, these words of “Lost Paradise”!

*

I would wish there were more than five parts of the world and that the oceans were more numerous. It is not enough to have one China and it is not enough to have one India! I would wish there were several pole-stars and a whole pack of Great Bears. How swift go the ships! How equal are the shores! How deceptive is the Southern Cross! The sharks are too few and the flying fishes fly hardly enough to make a parade of their little power of leaping. Faintly lit, the cities fade out and all the ports dwindle. The gulfs are thin like serpents, the islands have not the air of being water-ringed on all the sides and the revolving lighthouses are so low that one thinks always that they are on the point of being extinguished. The beauty of the world is less great than what one has dreamed in writing books of travel. One sole lamp is bright and shall not ever pale for all its smallness, scarcely a dust-grain of gold above the night of the oceans. It is the lamp of the pure spirit which needs no oil once it has been lit!

O ship, you can sail and carry me towards no matter what world, even beyond the Red Sea and beyond Greece, towards the country where reigns the fog and where turns the machine! There, on the shore that I leave behind me, is a man garbed in white who bears aloft a lustre for me despite the rain and the glooms which have suddenly spread. He makes a gesture of farewell, the gesture of a brother to a brother. I have no need to open the eyes in order to see him and the farther away I move the more brilliant grows his light.

________________

Lyrical and epiphanic ! One of the finest tributes [ to the Ashram] by a westerner.

Goes beyond a travel piece : cross-cultural understanding at its best!

Superb translation by Amal Kiran!

Sachidananda Mohanty