Dear Friends,

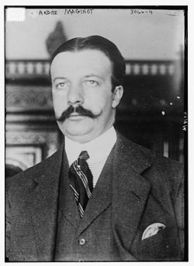

Maurice Magre (2 March 1877—11 December 1941) was a French poet, writer and dramatist. A staunch defender of Occitanie, he contributed significantly to make known the martyr of Cathares of the twelfth century. He was one of the most far-ranging and extravagant French writers of fiction in the first half of the 20th century, and perhaps the finest of them, because of the versatility of his imagination and the manner and purpose for which he deployed it. In the second part of his life, he became interested in esotericism. A seeker of spiritual light, he visited Pondicherry in 1935 to meet Sri Aurobindo.

This article is a translation of the chapter “L’Ashram de Pondichéry” in Maurice Magre’s book ‘À la Poursuite de la Sagesse’ published by Fasquelle Éditeurs, Paris, 1936. The Mother is reported to have remarked that Magre’s impressions were shot with a psychic vision. Thus they have an inner value in addition to the purely historical. This article has been translated into English by K. D. Sethna alias Amal Kiran.

With warm regards,

Anurag Banerjee

Founder,

Overman Foundation.

_______________________

The Ashram of Pondicherry

Maurice Magre

In the Ashram of Pondicherry are gathered together the wisest men of the earth. They dwell in white houses that look as if they were painted with some liquid moon. There is no sign on the door that here the souls have found peace. No star of the Shepherds gleams on their terraces and the Magi-Kings do not know the way to them.

The men of the Ashram are clothed in white cotton in the manner of the Hindus and their hair is twined in a sheaf upon their backs. They carry themselves straight like the spurt of a fountain, like a flame where there is no wind and like a thought when it is true. They move between low walls, in the gardens tended with care, they converse of things of beauty and they aspire towards the Spirit. These are the Perfect Ones amongst men.

The gardens of the Ashram have not the grandeur of those of Seville or the Alhambra. But it has seemed to me that there was a supernatural element which coloured the stems and the leaves. Does a Deva of the night come perchance to paint them before each dawn? On looking up, one sees the mango and the coconut. Hibiscus-flowers, at the tips of high branches, delicate and tossing like vivid thoughts, bend down over the walls and seem to look into the street, with a touch of pride.

*

Here is a community perfect in the measure in which perfection can be of this world. Each is devoted to his favourite task, according to his knowledge and his ability. There is a workshop for the carpenter, and a room where flour is kneaded. The bindings of books shine out like swords from the shelves of the book-cases. Through the open bays one sees like great marble pieces the brows of the readers. But most do manual labour, for in the handling of matter and in the attention that one gives to it there is a method that helps the soul. No bell is there for rest, and no rigorous discipline. Each finds his liberty in the harmony of love.

All the disciples have a beauty that cannot be defined, that is not contained in a system of proportions, that sports with the science of form. From where do they receive this beauty? Was it already enclosed in the germ-cells of their parents and has it merely blossomed through the mystery of life? Or did they receive it when they brushed past the grassless ground of the seven times purified courtyards, is it only the inferior manifestation of the grace of the spirit which alighted on them when they stepped through the gate of the Ashram? Who shall ever say from what hidden spring flows the beauty of the man of goodness, detached from the world? The most crystalline waters never reveal the subterranean soil that has filtered them and none has been able to see in the midst of the rock-masses, where all is frozen and granite, the precise point where takes birth the stream chosen from the hierarchy of streams to become the Ganges.

*

Behind one of the Ashram houses there is a silent courtyard where the gardener is king. Here are the cuttings of all the plants that, in the season of their growth, have to take their place in the gardens of other houses. And there are even some choice cuttings, grace-touched, that will be on the window of the Master and give a perfect flower in which he will contemplate at sunrise the manifold beauty of the earth.

The gardener knows this and he watches with a greater love over his delicate little people. He has pots of all shapes that are the homes of his sensitive children. According to their age and their capacity of changing the wet soil into the substance of their being, he transfers them from one pot to another, offers them a ray of the sun or a jet of his watering can. Here is the supple convolvulus, the brilliant hollyhock and the gladiolus with its perpetual offering. This courtyard is like a kingdom of delicate births, tiny weanings, slow outbreaks.

By his science of the virtues that reside in the seeds, of the humid forces that flow in the stems, of the distribution of the sap and its affinity with sun and moon, the gardener is the undisputed sovereign of the little inhabitants of the earthen pots, the radiant flowers of the future, all the beauty of tomorrow.

But he does not know his royalty. His face is so pure that one sees his soul through it, and in his soul are shining all the cuttings he has brought to flower. Is it perhaps because the gardener is in contact, within his narrow courtyard, with a wisdom of plant life which manifests through the aura of each leaf? Is it perhaps because he has silently communed with the soul of infant cuttings?

*

He is the most modest of disciples and yet his modesty is combined with an aristocratic pride. He explains by turns and he keeps silent and his speech and his silence have an equal timeliness. He makes one think of a very wise mandarin of North China born of a family as ancient as that of Confucius. I see him as governor of an immense province where the people bless him because under his administration finance has prospered, the harvests have been abundant and happiness has dwell in every home. In a palace of porcelain, he handles justice as if it were a fan and he metes out with a grand severity punishments that are absolutely trifling.

When he welcomed me on his threshold, I recognised him all at once. I would have recognised him out of all the inhabitants of India. I would have wished to tell him: “You are my brother.” I believe I merely said: “Good morning, sir!” There was a touch of raillery in the depths of his eyes, the raillery one has towards those for whom one has to show some indulgence.

He dresses at times like a Hindu and at other times like a European. His true country is the world of wisdom. But it is not there that I came to know him. I came to know him in some other age and I was then younger than he. He pulled me out of trouble again and again. Out of what trouble? I cannot say. He had often to forgive me and he did it with a smile. For what fault? Who will ever tell me? But is it all memory or a trick of the imagination?

What force enables you to know a large-hearted man? I had no idea that such a man existed. Surely I shall not find his like. But it is enough that there should be one of his kind in all this space stretched between the North Pole and the South.

*

The town stands on the sea-board within a circle of lakes and palms. A fiery sun scorches it perpetually and makes the tiles of its terraces glow. One who would contemplate it from an aeroplane would see only the flat and scalded stones around the status of Dupleix and the flag of the governor. The crows are heard calling to one another and sometimes there are silences that we find in no town. The bazaar lies stretched out in the dust. At the doors of the shops corpulent Mussalmans with thick lips offer their multicoloured stuffs. A canal divides the town in two, attesting by the filth which it drags with difficulty on its dead waters the eternal division of races. All along this canal, children play during the hours of the day, and at night the phantom of cholera glides silently over the slime.

Afar, the great steamers sail at times on the roadsteads, deliver their merchandise, whistle lugubriously and depart. In the little cafés, Hindu women dance to the sound of zithers, their hands behind their heads and the body held almost motionless. And always on the roofs the crows keep talking some incomprehensible language. It is in this town that, from all the quarters of India, wise men have come to live within the shadow of the Master, a shadow that projects a spot of light.

*

If the Master’s shadow illuminates the very moment it spreads out, of what matter then is moulded his body of flesh? A body resembling that of all other men. A body that is born of women, has drunk its mother’s milk, taken food, known the intervals of sleep and on whose head has grown hair and whose fingers have nails, in remembrance of far ancestors who have scrapped the soil and torn from it their life’s nourishment. The Master has lived among men of the earth, he has been to the West, he has studied the languages and the philosophies, crossed oceans, seen various peoples, taken measure of ignorance and injustice. He has suffered the oppression of his brothers and fought for their freedom. The human wisdom that he possesses he has wrested from day-to-day life just as one wrests one’s daily bread. It is by touching the roots of sorrow, the hidden and hurting sorrow behind the figure of all manifestation, like the soul behind the body, that his eyes have grown so deep and his face hollow, like a field when it is turned by a plough. But the divine wisdom, that is above all pain and cannot take part in it, he has come face to face with it in the solitude of a prison. The four walls of his cell, like shining mirrors, have allowed him to see what is given to no man to contemplate, the mystery of causes, the path that leads to the perfect union. Still as a cypress on a day without wind, as a stone fixed to the mountain by bonds of clay, he has pursued his infinite way which knows neither a milestone nor an inn, and he has reached the goal which makes man divine: It is since then that he has lived in two different worlds, perhaps uncertain of the one in which he finds himself, perhaps surprised to be always inhabiting a physical body. It is since then that those who had a presentiment of this realisation have come to live around him like bees around a wonderful queen who bestows a honey diviner than lies within the calyxes of the most beautiful flowers.

*

I have come from the barbarous West where the machine of the metal face is king and where men sell their souls in exchange for a little pleasure. I had embarked on a great liner with bridge over bridge and with smoke-trailing funnels and with sirens that tear the heart.

I had counted the days, I had counted the hours. At Port-Saïd I saw the pirogues of the Thousand and One Nights and at a little distance I passed the battleships where the guns glittered on their platforms and the flags sent signals. On the Red Sea I crossed above the carcass of dead ships and at night I saw their ghosts floating with their extinguished fires and the faces of their dead ones, eyes open, within the portholes. I saw the beacons turning and the birds in flight. I have come like a pilgrim a trifle ridiculous with his colonial helmet for a too burning sun and with provision of quinine against fever. There were in my bags a coverlet and a fan and books for the heavy hours.

O pilgrim with greying hair, what you lack is not faith. When I was walking up and down the bridge, I found the Indian Ocean limited in comparison to my hopes. The reefs of Minicoë were mere grains of dust in a desert of darkness before the mountains of diamond which appear to my gaze in the inner sea of my soul.

O pilgrim who have fixed your moment of departure in life’s twilight, did you not know that all beauty that manifests, from the top to the bottom of this earth’s scale, in a plant or in a man, needs the leaven called youth?

*

What would Edgar Allan Poe say in the nights of Pondicherry, streaming with sweat, under the square transparent shroud of the mosquito-net?

Ten thousand crows are perched on the trees and on the roofs surrounding my house and ten thousand times they repeat, “Never more!” with that pitiless regularity which only the hands of the clocks and the stars of the sky have. Never more, never more, why? What is the sense so mortally desperate of these syllables? What is it that never more will come? Is it the gaiety of youth, the possibilities of manly force? But it has been long since I gave up this morning-heat of the blood which awakening brings you and which is sweeter than any intoxication. I have accustomed myself to hear my heart beat, measure my strength, consider my organs like the pieces of a clock-work ill-adjusted by an artisan miserly of nerves and tissues, one who has scamped his job of human construction. Is it lost pleasure, the pleasure of the body needing to exalt itself in order to escape from the void? Is it the waiting at the door which opens with a crumpling of robes, with the melancholy odour of hair? But, like the man in charge of the accessories in a theatre, I have scraped together, once the show was over, the paper bouquet, the rouge-stick and the false letter and I have consigned them to a cardboard box for the next show which will not take place.

Why do the crows repeat “Never more” in the endless night? Never more the peace of the room with books lined up, books where beauty lies hidden and can leap forth, where wisdom is at rest and does not display itself. Never more the hills bathed in sunshine, the vines which bend over on themselves, the parasol pines like offertories, the paths which slope down like old happinesses? Never more the welcoming little hotels, the friends whom one meets, the tables on the terraces when night falls? Never more the things I have loved? But no, it is not that.

What is engraved in memory comes alive the most forcefully when thought recreates it and I can, like a magician, resuscitate at my wish the miserable enchantments that have adorned my ordinary-man’s life. It is over something else that the night-crows are moaning. It is perhaps not concerned with happiness. There is a Never Moe which keeps resounding in the abyss of the soul where the consciousness has never descended. It is a lament over forgotten secrets, over beings one has known in dreams, over the beauty of landscapes in other worlds.

Oh the Never More of burning nights, how it tears, how it goes far into the possibilities of anguish, when the day is first breaking, when there are at a distance the indifferent breakers of the sea and the siren of a steamer that calls one knows not what, one knows not whom, undoubtedly death.

*

Between the Master and the disciples there is the Mother. The Mother is at the same time a woman, made of flesh and bone, with face and hair, and the metaphysical symbol of the world-soul. One invokes her as the essence of life, the animating power of things and one takes refuge in her feminine arms if a wound of the body needs tending. One sees the Mother glide over the terraces of the Ashram as fleeting as an ideal thought in a daily dream. She has established an unformulated language based on the correspondence that exists between flowers and human wishes. The giving of a flower by a disciple is enough for her to know that some disquiet has to be soothed, some prayer to be granted. The Mother is close to the Master as the shadow is behind a man and as a ray is before the mirror when it is turned towards the sun.

*

When I stood before her, it was an if an inner storm were let loose all of a sudden. It came from the depth of the soul’s horizon, with clouds of sombre thoughts and with breaths of revolt.

The Mother wears a sari of grey silk with an embroidered border and round her head a band with the same embroidery as that of the voile. Her white buskins make her feet snowy. She seems to me so small in her form and so great as a symbol! Her hands are so delicate and well-tended that one would say they were made of jewels from another planet. When she pushed the door a breath of adoration penetrated after her like a fume of sacred gold. I felt gliding up to me a dancing light which passed through my heart. But one never gets what one expects. Just as at the age of ten I started weeping after having received the wafer of holy communion, so also, hoping for serenity, I saw disorder arrive. The Spirit touched me and I knew not that it had touched.

*

Between the Master’s house and the street where men pass, there are trees. And on these each evening, with a great rustling of wings and cries of all kinds, thousands of birds alight. Never in any garden of the earth have there been so many gathered together. On all places where rise the prayers of man, there are birds that descend. For there is a secret rapport between birds and the spirit. As if the trees of the garden were blossoming in the spiritual world, all the birds of the region come to perch on their branches. But it is not for going to sleep, according to the law of creatures, when night falls. They exchange a thousand words in a language that has no contact with human speech. What they say remains ever incomprehensible to us, for they do not feel emotion either tin time or space, and the quality of the things they communicate is of another nature than our thoughts. When everything has been said, everything that the birds have to say after a day or flight over the grain-bearing earth, they lower their wings little by little, they slowly grow still. The garden of the Ashram, when the moon makes its appearance, is covered with thousands of tiny statues—beaks bent, feathers marbled.

*

What difference is there between a cricket of Toulouse and an Indian cricket?

The voice of the Indian cricket is perhaps more ringing but the spirit of their song is the same. The one that is singing in the little garden under my window is as much at ease in the shadow of a banana tree as its brother of the banks of the Garonne between the vine and the cypress. Both of them have learnt the same things while touching with their antennae different earths in which they dig similar tunnels.

To the man who hears them they speak of the happy chances of life, they promise good fortune and the evening-contentment which a calm conscience brings. All the crickets of our planet sing the same little benevolent hymn and if a cricket of genius adds somewhere a new note it is soon transmitted mysteriously to all the crickets of the earth.

I come to bear witness to one of these innovations. The cricket I am hearing this evening has struck upon an unpublished theme. It is almost a trifle, just two or three notes. I am indeed at a loss to translate them. A cricket’s song is so mysterious!

I thank the cricket of Pondicherry for the way it played on its tiny instrument. When I shall walk along the Garonne at the hour when the small farms light their lamps and poplars rustle, all the crickets of Languedoc will add for my sake to their song what the Indian innovator of genius has found, something indefinably deep, a mere nothing, the shadow of a palm, the vanished traits of an unknown brother.

*

I have crossed a part of the earth in order to draw nearer to the Divine. A child of five could have told me that this was unnecessary and that God is for ever by the side of each one. But all the children of five are wrong. Thanks to the faculty that is natural to him and thanks to the impetus of his soul, a man in his life-time can communicate with the worlds of the spirit. He makes his miraculous power radiate on those whom he loves. But he gives only infinitesimal drops, imperceptible luminous atoms. It is not because he is miserly. But the spirit, in order to be received, needs a prepared soul. Mine has gone through no preparation. Wrapped in my proud grossness I remain in the garden of the birds, I who have neither their wings nor their gift of song, I who would pose questions instead of staying on a branch and sleeping till the dawn.

*

O Master, we do not see your shadow at the window nor do we hear the noise of your steps making the ceiling resound. You sit in perfect solitude: the divine serenity, the realised ecstasy. My admiration lifts towards you in the silence of the night, towards you who have crossed the gate of perfection.

But there is a contradiction that makes me suffer and whose obsession I cannot chase away, for each of us carries his thought like a sharp sword turned towards himself and every movement of the soul causes a rending. You teach the beauty of living forms, the task of perfecting man and nature and making the world flower according to the divine law. But the divine law is not observed, men even misconstrue it, injustice reigns and evil is lord. And then, O Master, I tell myself that if you pass over the dust of the roads, if you go into the cities, placing the palm of your hand on the heart of the untouchables, surely the deaf will hear and the lepers get healed and the world realise salvation.

Ah! the evening when I have walked through the empty street by the side of the house where you live, I have passionately heard — even if I did not listen from the other side of the wall — the sob that the misery of mankind drew from you.

It was childish, I know it well. And that evening it seemed to me that I saw your tears pass through the stone like diamonds of fire and that the breath of your pity came up to me and burned my heart.

*

The ship that brought me, with its tiers of bridges and its underground machinery, is like a reduction, a microcosm of this planet.

Guided by the compass and the sextant, it goes over the sea like the earth in space, held in equilibrium by the law of attraction. And it transports many different worlds. There is the paradise of the first class where live the chosen, enjoying the presence of God, their God who is the appeaser of the hungers of their bodies.

With the smoke of cigarettes and the whiff of whisky rise the mediocre dreams of these fortunate ones. Like grotesque angels the barmen and the cabin boys run to satisfy their least desire and the orchestra sets women in evening-gowns dancing, while Mount Sinai and the dunes of Arabia are outlined on the horizon. Just as God the Father admits into a particular seventh heaven certain saints or certain meritorious lucky ones, so also the captain of the ship makes certain choice passengers climb a little iron staircase to offer them a superior whisky on the bridge that is nearer the stars.

Immediately below is the intermediate world, with the angels less diligent, an orchestra more ordinary, cabins narrower. It is the purgatory of the proud. Hardly one light chain divides them from the creatures who are the elect and who live in paradise. They could make it give way by their little finger. But this chain is strong like the prejudices of money whose symbol it is, like the power of society. Its mediocrity must be paid for in pain. The tormented ones of this purgatory do not know that their lungs suck the same air, their eyes look at the same light, they are condemned to the rack of envy.

And lower, much lower there is hell. Hell is hidden in the depths of the ship. It is invisible but everyone knows of its existence and refuses to think of it. Hence there is another humanity whose face one does not imagine, whose torture one does not wish to know. They are Arabs, it is said, or perhaps the Chinese. As in the descriptions of the catechisms, hell is a fire. The sinner is tormented by the flames. The ladder by which one descends is so hot that the hand of flesh can scarcely be put on it. Here there is the mystery of electricity with its levers, its wires and its tubes. There is an alley of metal where the air crackles and which is lined with the cylindrical masses of the boilers where the blue and red oil-fuel dances. And there live, in the darkness and the fire, anonymous beings whose eyes are hollow, whose chests are desiccated. But what fault could they have committed to be condemned to icy jets from plug-holes of air and steam from orifices of red-hot steel, condemned to hear, like the knife of a guillotine, the panel of automatic doors fall behind them?

And the ship goes on, driven by the inner power which it draws from the force of mute suffering; it transports within the circle of its armature the iron of the worlds in which no Virgil will explain to any Dante the secret causes of injustice and sorrow.

*

If I, the most egoistic of men, am touched by another’s suffering down to the roots of my being, I ask myself what it must be in your being and how the fires of sorrow have not completely burnt you up in the room where you sit. If I look at your face I see as far as one can go into the depth of pity. To have those eyes of sorrow and that tearing sadness on the features, you could not but have absorbed the misery of illness and the still greater misery of the spirit. Your body must have oozed with the ulcers of the wretched, swollen with the bloat of the leprous. Your soul has felt the dissoluteness of the unbeliever, the despair of those who know not how to love, the abysm of the suicides.

And yet you sit in your white house at Pondicherry, hear the come-and-go of the disciples, see through the window the flowers burgeoning? Are you protected by a formula that the sages have handled down since the Vedic ages? Do you conceal your self in a veil of virgin gold that the Seven Aryan Rishis wove with their hands ten thousand years ago?

Does there exist for man a protection against the sorrow of his brother? Or does one escape this sorrow by following the path of silver that leads direct to God?

*

But perhaps pity is not a high virtue. It touches on our physical senses, it moves us to our entrails, it comes almost always with an egoistic emotion. The misfortunes that strike home to us the most are those that we dread for ourselves or that we have known in the past. Our wounds, our revolts, from which we secretly draw pride as from an inner nobility, are only the passionate signs of our frenzy for life. One pities those who lack in happiness. But happiness is not life’s goal.

Fortunate is he who has been able to put himself in the region where good and evil appear like the two sides of one and the same medal, he who sees the divine presence moving in the sorrow as in the joy. Pity is for him only the memory of a time when his vision was limited and his comprehension less wide.

O divine joy of the perfection in which one touches the prime substance of creatures, is pierced by vibrations of the radiant intelligence, is merged in the ineffable love which sustains the world!

*

She [1] looked so intensely at the horizon, the horizon of the Eastern sea on which the windows of the Ashram open! When she kept herself seated in the prow of the ship, I believe I saw her prayer materialised above her like an aura of sapphire mist.

All that she told me about the life of the soul had a profound resonance. Like a magician who with a want makes flowers break open in the barren earth, she gave birth in me to beautifully coloured thoughts.

It is always doubt that one utters with the greatest of ardours, for doubt is more living that faith and more avid of utterance. But her faith was so intense that as soon as I expressed a doubt before her, she dispelled it, without vain words, with nothing save that inexpressible warmth which comes from the hearth of the soul.

But a fire of such a nature, does it not get burnt up just because one warms oneself with the flame? According as my faith increased, it seemed to me that there was something in her which grew faint. And when my aspiration towards the spirit reached its highest point, a breath of dryness passed over her and brought her a mysterious despair.

Doubt is a sickness of the soul which periodically returns like certain fevers. O Master, cast a look on her who has generously poured the invisible riches. Penetrate her with your creative thought so that from now on she may carry certitude just as a warrior carries an enchanted sword by which he is saved from evil. Grant her the talisman which gives the unchangeable virtue of belief. It is she who deserves the gift of the Master, if it is true that faithful hearts should be the first and that sincere enthusiasm is superior to all knowledge.

*

[1] Here the author seems to refer to one who accompanied him to Pondicherry as secretary and nurse.

___________________

An extraordinary piece of psychic depiction indeed ! It touches the heart more, than the mind.

Thanks for this sharing.

Lyrical and epiphanic ! One of the finest tributes [ to the Ashram] by a westerner.

Goes beyond a travel piece : cross-cultural understanding at its best!

Superb translation by Amal Kiran!

Sachidananda Mohanty

Absolutely fascinating – an extraordinarily exotic memoir which is superbly saturated with sensitive glimpses of the Ashram life well attended with adoration of the Divine Mother in poetic ambiance of the highest order – here meets mysticism , philosophy , literature and silken like sentiments in wonderful manner –

Surendra s chouhan SAICE ’69

When we were kids, in the mid-1950s, sentences from this dream-wordly exploration in French used to haunt us: “They dwell in white houses that look as if they were painted with some liquid moon.” Only a poet of Amal’s trans-cultural sensibility could help so skilfully “starting” wings with their full significaton behind their stone-abodes of heavenly peace. Another specimen of psychic presence in French literature seems to have been recommended by Sri Aurobindo, in the novel “Lucienne” by Jules Romains, more popular for his play, “Knock”. Informed that the Mother had known this eminent member of the French Academy, I met him in Paris in 1971, shortly before his death. That was thirty years after Magre’s passing.