Dear Friends,

In his childhood, Dr. Prithwindra Mukherjee (born in 1936, Kolkata) listened to tales of his grandfather Jatindranath Mukherjee or Bagha Jatin from ‘Bordi’, the latter’s elder sister Vinodebala Devi. In 1955, inspired by written notes left by Bordi, Dr. Mukherjee began investigating the life and times of Bagha Jatin. It began with correspondence with those who had known Jatin, and in 1963, invited by Bhupendrakumar Datta, one of Jatin’s loyal followers and former Jugantar leader, he interviewed surviving revolutionaries connected to Jatin.

Along with other documents from the state and national archives, recommended by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Dr. Prithwindra Mukherjee was the first to consult microfilms on the Indo-German collaboration (an original contribution of Jatin) as intercepted by Anglo-American Intelligence during World War I.

The following is a two-part series of reminiscences by Dr. Mukherjee about his legendary grandfather published on the occasion of the 106th anniversary of Bagha Jatin’s martyrdom.

With warm regards,

Anurag Banerjee

Founder,

Overman Foundation.

Bagha Jatin: The Freedom Fighter Who Sought to Capture Fort William

Dr. Prithwindra Mukherjee

(I)

On 10 September 2015, observing the centenary of Bagha Jatin’s martyrdom, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced in a tweet: “His courage and sacrifice for our Motherland will always be remembered.” Bagha Jatin was a popular nickname fondly attached to the memory of Jatindranath Mukherjee (1879-1915) for his valour and vision.

Professor Tapan Raychaudhuri writes: “Bagha Jatin, alias Jatindradranath Mukherjee, is one of the legendary figures in the history of revolutionary efforts in India. The truth of this matter is unfortunately shrouded in inaccurate tales. Bagha Jatin was involved in the German Conspiracy Plot during the First World War, hoping to get arms from the Germans for a country-wide uprising, but died fighting the British Army and police before the arms could arrive. (…) The Tiger had a very sophisticated understanding of contemporary political reality. He (…) hoped to inspire his countrymen with the ideal of self-sacrifice in the cause of independence and by his own example fill them with courage. This accurate description of his struggle with the ruling colonial power shows the nature of the initiative and also the impact it had on the national psyche…”

On April 1, 1906, armed with only a Darjeeling dagger, Jatin had to face a Royal Bengal tiger in a wrestling bout, to save the life of an adolescent. On the point of exhaustion, Jatin mustered his last drops of strength to plunge the dagger through the tiger’s neck.

Several associates of Jatindranath Mukherjee remembered their leader’s concern about capturing Fort William to paralyse the colonial system of protecting the interests of the Crown. Some of them, even though divided into various political factions, united their voices in 1972 to demand the renaming of Fort William as Jatindra Mukherjee Qilla or Bagha Jatin Qilla. A total of 87 members of the Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha, representing all major political parties, signed the Petition and submitted it to then Defence Minister Jagjivan Ram. Keeping in mind the centenary of Jatindra Mukherjee’s heroic martyrdom on September 9, 1915, let the Prime Minister accept this proposal concerning the memory of one of India’s most outstanding freedom fighters.

Bagha Jatin, the man

Having lost his father Umeshchandra at the age of five, Jatindra and his elder sister Vinodebala grew up under the stern and loving care of mother Sharat Shashi, a poet and devoted reader of contemporary Bengali essayists. She had taught them that to serve humanity was the same as serving God. Always a daredevil, a 14-year-old Jatin risked his life to calm a frightened horse in order to save the life of an infant in Krishnanagar, a story made famous by posterity.

Personally encouraged by Swami Vivekananda, Jatin extended his social service to the cause of ridding India of her foreign rulers. Seeking to improve his self-defense skills at the gymnasium run by the Goho (Guha) family, the dauntless Jatin was fully abreast of the editorial dialogue between Bipinchandra Pal and Rabindranath Tagore on the tragic problem of gratuitous insults to the “natives” from colonial rulers. Tagore’s immediate solution was the tonic of the “clenched fist”.

Very soon to become famous as a “local Sandow (the renowned Prussian bodybuilder)”, owing to his frequent interventions against arrogant British military officers posted in Fort William, in the winter of 1905, Jatin took advantage of the visit of the Prince of Wales to distract the citizens raging against the Partition of Bengal. He invented his own means to point out to the future Emperor that it was the dregs of British society who had been appointed to govern India. On his return from India, the Prince consequently had a long conversation with Secretary of State John Morley on May 1o, 1906, on the ungracious bearing of Europeans toward Indians.

On April 1, 1906, armed with only a Darjeeling dagger, Jatin had to face a Royal Bengal tiger in a wrestling bout, to save the life of an adolescent. On the point of exhaustion, Jatin mustered his last drops of strength to plunge the dagger through the tiger’s neck. Taking upon himself the responsibility of curing the fatally wounded patient, leading surgeon Suresh Sarbadhikari published a tribute to Jatin, ‘The Nimrod of Bengal’, and it won him the fond nickname of Bagha Jatin, for his tiger-like valour.

Swami Vivekananda’s brother, Bhupendranath Datta, mentions having spoken to Jatin in December 1906 — while he was still convalescing after the bout with the tiger — during a closed-door meeting of Jugantar leaders, presided over by Sri Aurobindo. Jatin admitted that the much needed funds for furthering the freedom movement could only be secured by dacoity; but that the victims would be informed that the money was to be treated as a loan, to be repaid after Independence.

Still limping on legs mauled by the tiger, Jatin enacted the crowning episode of this pageant in April 1908, at Siliguri railway station. Single-handed, he felled four cheeky English military officers. The Indian press published such a fulsome and celebratory account of this event that the officers’ legal advisor withdrew the case against Jatin. Asked by the Magistrate to behave properly in future, Jatin regretted that he could not promise to refrain from similar actions as part of his duty to vindicate the rights of his countrymen.

Riposte to Repression

At this juncture, history took on a faster tempo. Having frequented the secret society called Anushilan Samiti since its inception in 1903, Jatin joined Sri Aurobindo as the latter’s right-hand man to prepare a powerful underground revolutionary movement, recorded as Jugantar by the colonial police. Their final objective was to declare an 1857-type of war of independence throughout India, with the participation of officers and soldiers from various cantonments.

Several associates of Jatindranath Mukherjee remembered their leader’s concern about capturing Fort Willaim to paralyse the colonial system of protecting the interests of the Crown. Some of them, even though divided into various political factions, united their voices in 1972 to demand the renaming of Fort William as Jatindra Mukherjee Qilla or Bagha Jatin Qilla. A total of 87 members of the Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha, representing all major political parties, signed the Petition and submitted it to then Defence Minister Jagjivan Ram.

Contrary to the highly centralized organisation at Maniktala Garden under Barin Ghose as sole leader, Jatin the strategist had been creating decentralized and loose confederated regional centres under a local leader, who ignored the responsibility given to the leader of his neighbouring unit. This pattern ensured that even if a unit or two was paralysed, the general scheme would continue to function undisturbed. Sensing that Barin’s push towards an untimely showdown was likely to drive him to an abrupt end, Sri Aurobindo warned Jatin against visiting Maniktala Garden.

On April 30, 1908, Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki — mandated by Barin — assassinated two innocent English women at Muzaffarpur, mistaking their coach to be that of an English magistrate black-listed by the revolutionaries. A total of 33 Jugantar activists were arrested, and the Alipore Conspiracy Case began, with Sri Aurobindo accused as the mastermind. Though Jatin’s name was pronounced as “one of the principal leaders of the movement”, his strategy of a loose federation helped him escape and rally the remaining stunned, absconding militants.

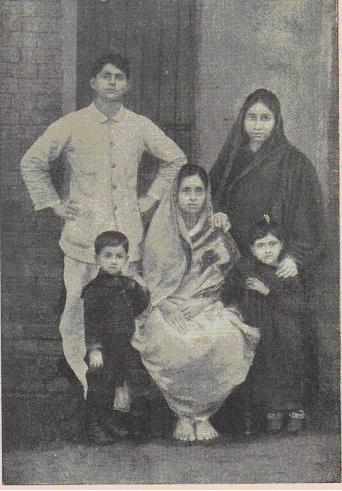

Jatindranath Mukherjee alias Bagha Jatin in 1912 with his sister Vinodebala Devi (seated), wife Indubala Devi, eldest son Tejendranath and daughter Ashalata.

(II)

Since 1908, repressive laws banning all associations had left Jatin with a massive task. First, to provide proper legal defense to accused revolutionaries. Second, to undertake secret tours in the districts to consolidate links between units. Responding to his efforts in a consistent and coordinated way, absconding regional leaders reflected the one single policy summed up by the colonial police as the “Jatin Mukherjee spirit.” Jatin also executed a third and most significant task: registration of the Bengal Young Men’s Co-operative Credit and Zemindary Society at Gosaba, leasing from the philanthropist Sir Daniel Hamilton a few acres of land to provide boarding and lodging to “wayward” young men.

Jatin adopted the experimental method of his friend, educationist Shashibhushan Raychaudhuri: run night classes for adult villagers, polytechnique schools for volunteers, establish rural libraries and charitable dispensaries with ayurvedic and homoeopathic facilities; encourage them with small-scale cottage industries, swadeshi stalls, wrestling clubs, racing, rowing, gymnastics, even cricket. Jatin also picked up competent candidates to practise shooting in the marshes. Sir Daniel offered more plots of land for another branch of this society at Kaptipada near Baripada in Orissa.

According to Nixon’s Report, during three years from May 1908, following arrests and the protracted Alipore Case, and the publicity given to the revolutionary methods, Bengal knew “a very severe anarchical time”. Jatin and his followers executed several “acts of daring and desperate self-sacrifice… to revive the confidence of the people in the movement,” writes Arun Guha. “Nobody outside the innermost circle suspected his involvement. Secrecy was absolute in those days, particularly with Jatindra.”

In addition to ten sensational operations, Jatindra chose four daring murders to serve as a warning to ‘traitors’ of the people’s cause: (a) August 1908, approver Naren Goswami murdered in prison; (b) November 1908, police sub-inspector Nandalal Banerjee murdered on the open streets of Calcutta for having arrested Prafulla Chaki; (c) On February 10, 1909, public prosecutor Ashu Biswas murdered inside Calcutta High Court; (d) On January 24, 1910, dynamic deputy superintendent of police Shamsul Alam shot dead, once again in the corridors of the High Court.

On January 25, 1910, unnerved by the assassination of Shamsul, Viceroy Minto openly declared how “a new spirit” — meaning Jatin Mukherjee — “of anarchy and lawlessness (…) seeks to subvert not only British rule but the Governments of Indian Chiefs.” Minto left India hurriedly.

On January 27, Jatin was arrested along with 66 members of Jugantar. On March 7, 1910 began the Howrah-Shibpur Case — a sequel to the Alipore Case — under Sections 121-124, 302 and 400 of the Indian Penal Code. Hardinge, the newly appointed Viceroy, took no time singling out Jatin as “the one criminal” and concluded: “Nothing could be worse (…) than the condition of Bengal and Eastern Bengal. There is practically no Government in either province.” Reason for shifting the Capital from Calcutta in turmoil to “empress Delhi”.

Inroads into the Army

The barrister Kennedy had drawn Jatin’s attention to the way the Indian budget was being squandered by the Crown to protect its territorial interests in distant nooks of the Empire. He wanted Indian soldiers to think and act patriotically. It turned out to be one of Jatin’s original contributions: that of indoctrinating native soldiers in various British regiments inside India and all over Asia, inviting them to join the insurrection. During the Howrah Gang Case 0f 1910-1911, when Jatin was tried with 46 co-accused, the charges were of waging war against the Crown and tampering with the loyalty of Indian soldiers posted in Fort William and commanding other Indian cantonments. Several officers of the 10th Jat Regiment faced court martial for complicity in sedition, before it was dismantled forthright. Recognising the 10th Jats’ case to be part and parcel of the Howrah Case, Hardinge wrote: “With the failure in the latter, the Government of Bengal realised the futility of proceeding with the former…”

During Jatin’s trial, several eminent militants — like Nikhileswar Ray Maulick and Naren Chatterjee — were singled out for maintaining links with Army officers: first, taking them to secret meetings at Nanigopal Sengupta’s house at Shibpur or later, to the Khidirpur centre under the guidance of Sarat Mitra. Second, moving about with them to meet officers-in-charge of barracks in Benares, Nainital, Lahore, Peshawar etc.

Jatin adopted the experimental method of his friend, educationist Shashibhushan Raychaudhuri: run night classes for adult villagers, polytechnique schools for volunteers, establish rural libraries and charitable dispensaries with ayurvedic and homoeopathic facilities; encourage them with small-scale cottage industries, swadeshi stalls, wrestling clubs, racing, rowing, gymnastics, even cricket. Jatin also picked up competent candidates to practise shooting in the marshes.

H.E. Arsenyev, Russian Consul-General in Calcutta, informed St Petersburg on February 6, 1910: “Despite the British authorities’ desire to keep the affair from becoming public, some details have come to light (…) that conspiracy was connected with the liberation movement which had been gaining momentum in India in recent years…” About the conspirators’ trial, the Russian paper Zemschchina wrote that the sepoys had conducted themselves with great poise. They declared that they had joined a revolutionary union set up by Bengali patriots, and were aware of the fact that they wanted to overthrow British rule in India. Their claim: “Don’t think there are only 25 such sepoys. Oh no! There are many such sepoys, and the fate of British domination in India is in our hands.” Even after the Howrah Case was over in April 1911, while Naren Chatterjee was absconding to avoid arrest, the Khidirpur group, led by Ashutosh Ghosh and the Howrah group under Durgacharan Bose, maintained contact with native officers of Fort William.

Thanks to Jatin’s strategy of a decentralized organisation, none of the undertrial militants of Jugantar could be proved guilty, contrary to the accused in the Alipore Case under Barin’s heroic confession, except Sri Aurobindo, who refused to make a statement. There were only two militants in the Howrah Case who turned approvers.

German Collaboration

Interned at home even after his release, dismissed from his job, Jatin managed to meet the Crown Prince of Germany on his visit to Calcutta in 1912, and obtained from him the promise of arms and funds from Germany in case there was an insurrection during the imminent war between England and Germany. Judging from the lull until Jatin’s return to violence in 1914, the authorities did not fail to notice the rigorous command Jatin had over the violence he had unleashed before going to prison.

*

One of the most threatening events of the return of Jugantar with its policy of counter-repression was the revolutionaries’ helping themselves to 50 sophisticated Mauser pistols with 46,000 rounds of ammunition from the godown of Rodda & Co, a British firm. Director of Surveys J.C. Nixon shared the militants’ sentiment of personal devotion for Jatin: “He seems to have had a most extraordinary influence over his followers, who looked upon him with something approaching reverence and awe.”

Since 1906, in batches, Jatin had been arranging trips abroad for his emissaries for higher education along with two more objectives: (1) learn as much as possible the techniques of military craft, with manufacture and proper use of explosives; (2) create a public opinion favourable to India’s attempts to get rid of British domination. Tarak Das in the United States represented the most loyal model of this mission. Others like Shrish Sen, Guran Ditt Kumar, Adhar Laskar, Satyen Sen, Khagen Dasgupta, and Surendra Bose in Europe and America showed their efficient devotion to it.

There were others too. As soon as war was declared in 1914, and inspired by Jugantar, Virendra Nath Chattopadhyay (‘Chatto’, brother of Sarojini Naidu) came to an agreement on a 15-point treaty — known as Plan Zimmermann — with the Imperial German Government: Germany was to give Indian revolutionaries arms, explosives, monetary help and officers. But no German or Turkish Army was to advance on a liberation mission. Shrish Sen as Jatin’s emissary was at once contacted by Chatto.

Also at Chatto’s request, Baron Von Oppenheim of the German Foreign Office informed Indian students in 31 German universities about this plan. An immediate response came from a large number of students and professors — Hindus, Muslims and Parsis — hailing from various parts of India.

Whereas Jatin’s emissaries in America — mainly Tarak Das and Bhupen Datta (Vivekananda’s brother) — had been simultaneously trying to contact the German Crown Prince about his promise, by October 1914 they had received an invitation from Chatto to join him in Berlin. N.S. Marathe and Dhiren Sarkar (brother of Benoy Sarkar) had carried a message from the Kaiser himself for Von Bernstorff, the German Ambassador in Washington, to sanction funds to help an insurrection in India. Military Attaché Von Papen received orders to arrange for steamers on the California coast and purchase adequate arms and ammunition to be delivered to the “eastern coast” of India. German consulates in New York, Chicago and San Francisco supplied money and facilities to Indians rushing to join Chatto in Berlin. Gadar Party members had already started reaching India by the thousands.

Rashbehari Bose

Drifting away from the mainstream, momentarily dejected, Rashbehari accompanied Motilal Roy and Amarendra Chatterjee on the flood relief effort in 1913, to meet Jatin. Before Sri Aurobindo left for Pondicherry in 1910, both the Jugantar leaders had received from him the instruction to follow Jatin. Faithful to his mission of an insurrection, Jatin set ablaze Bose’s passion, while the latter discovered in Jatindra “a real leader of men”. During several meetings with Bose, one day Jatin asked him whether he could organise the occupation of Fort William. Accepting the challenge, Bose set out to negotiate with a new set of native officers, distinct from those contacted earlier by the team of Naren Chatterjee. In need of further moral sanction for serving as Jatin’s assistant, Bose sent Motilal to Pondicherry: Motilal returned in November 1913 with Sri Aurobindo’s full approval. Owing to his familiarity with Benares, Bose received the charge of North Indian units and barracks. In addition to the organisation in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, Jatin chose to guide emissaries in Europe and America. The Berlin Committee was to raise an army of liberation by recruiting Indian soldiers from various Anglo-Indian regiments imprisoned in the Middle East: synchronizing with the insurrection from Bengal to Peshawar, they would reach Peshawar through Afghanistan. In a pincer movement, the Gadar leaders under Tarak Das would storm through Thailand and Burma, reach Calcutta, seize Fort William, and join Peshawar.

On January 27, Jatin was arrested along with 66 members of Jugantar. On March 7, 1910 began the Howah-Shibpur Case — a sequel to th eAlipore Case – under Sections 121-124, 302 and 400 of the Indian Penal Code. Hardinge, the newly appointed Viceroy, took no time singling out Jatin as “the one criminal” and concluded: “Nothing could be worse (…) than the condition of Bengal and Eastern Bengal.

In November 1914, Satyen Sen reached Calcutta, with V.G. Pingley, Kartar Singh Sarabha and an important number of Gadar militants. Charles Tegart had recorded Jatindra’s strategic winning over of Sikh soldiers of the 93rd Burma Regiment (on the eve of their departure for Mesopotamia). Jatin took Satyen to the garden at Baranagar, where they interviewed these soldiers. After several talks with Pingley and Kartar Singh, in the third week of December 1914, Jatin sent them to Bose with necessary instructions.

Bose learnt from them that in addition to four thousand Gadarites who had already returned from America, many more would arrive once the rebellion broke out. Obeying Jatin’s wish, from Benares, Bose sent Pingley with Sachin Sanyal to Amritsar to meet Mula Singh (who had received Satyen at Shanghai). Invited by Bose to appraise the situation in Upper India and to expedite preparations for the rising, Jatin with his family, Atul Ghosh and Naren Bhattacharya set out “for pilgrimage” to Benares, in January 1915.

Despite having won over the 16th Rajput Rifles in garrison in Fort William through Havildar Mansha Singh, Jatindra had preferred waiting for the insurrection till the delivery of the German arms, which would be valuable and indispensable. In the German Foreign Office papers, we come across Bernstorff acknowledging on 7/12/1914 Papen’s purchase of 11,000 rifles, 4 million cartridges, 250 Mauser pistols, and 500 revolvers with ammunition for India. Further on January 9, 1915, Von Oppenheim confirmed the arrival of Professor Barakatullah in Berlin from Washington (collaborating with Tarak Das) and that 30,000 rifles and 5,000 automatic pistols were ready to be dispatched. But according to Bose’s hasty estimation, the Gadar militants, growing impatient for action, were reliable for the purpose. Therefore Jatin, the commander in chief, accepted Bose’s proposal and sanctioned February 21, 1915 as the date of the insurrection.

Failure: A double betrayal

The first blow came in spite of Bose’s watchful eyes: the betrayal by Kripal Singh, a police agent who had been keeping the Imperial Authorities abreast of the decisions taken by leaders of the rebellion. Even on learning that the plot was going to miscarry, Bose turned to Jatin, asking for money. Jatin accordingly improvised two taxi cab robberies on February 12 and 22, 1915, collecting 40,000 rupees, a fabulous booty.

Accepting the futility of trying to restrain the activities of Indian leaders like Taraknath Das, Maulavi Barakatullah, G.D. Kumar or Harnam Singh abroad, and encouraged by the Anglophile President Woodraw Wilson, the British Foreign Office intensified its intelligence network on American and Canadian soil. An agent was introduced in the Department of Justice in Washington D.C. Having recruited refugees from Eastern and Central Europe, a strict chain network watched the shipping of all Germany-bound contraband materials.

Appointed by Calcutta Police, W.C. Hopkinson, who had followed Taraknath to America, discovered that the wayward lifestyle of Jugantar leader Chandrakanta Chakrabarti and his friend Ernst Sekunna could be of immense help. The address of 494, East 141st Street at New York owned by Sekunna had an apartment rented by the Vedanta Centre, presided over by Swami Abhedananda, who had initiated Chandrakanta as a Brahmachari; Chandra had rented the entire basement for living with Ernst. The housekeeper was a Czech refugee who informed Hopkinson that the basement was frequented by many Indians arriving from India, England, France and Germany, and a host of doubtful literature and newspapers from all over the world was to be often found. An ideal prey for an adventurous housekeeper, who was a member of the Czech network of counter-espionage directed by E.V. Voska.

On learning from Hopkinson the scheme by Jatin to free India with German collaboration, Voska rushed to inform the pro-American, pro-British and anti-German T.G. Masaryk (future President of the Czech Republic). The U.S. authorities passed the news immediately to the British police. Ross Hedviek, a Czech author, writes that had Voska not interfered, nobody today would have heard of Mahatma Gandhi, and the Father of the Indian Nation would have been Bagha Jatin.

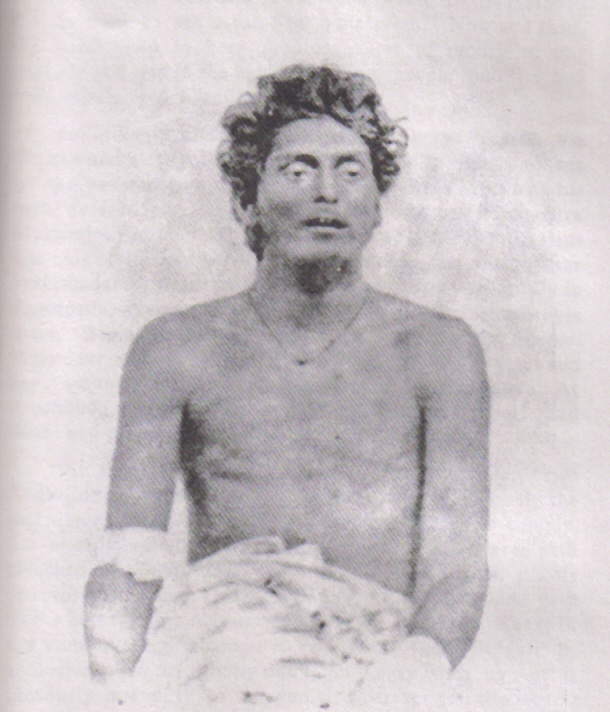

Whereas, in Balasore, Jatin sacrificed his life after enacting with four associates a heroic battle against an armed police regiment on September 9, 1915, Rashbehari Bose collected more money from Jatin’s associates and fled to Japan, convinced that by he would live to cause a bigger revolution in the future.

Jatindranath after the battle of Balasore.

Bagha Jatin: Impact on the national psyche

Historians such as Bhupendrakumar Datta have compared the vacuum created by Jatin’s martyrdom with the people’s spontaneous mourning for Gandhiji on January 30, 1948. Jatin’s loyal disciples sensed that there was no room for dejection in the life of a revolutionary. On returning from South Africa in that significant year of 1915, Gandhiji discovered an entire generation prepared to rise in the name of the Motherland; drawing inspiration from the doctrine of passive resistance that Jatin had received from Sri Aurobindo and had transmitted to his followers. Gandhiji skillfully obliterated the “armed riposte to violence imposed” from it, and promising to win over self-rule (swarajya) within a year, he imposed his absolute faith in “non-violence”.

Whereas Jatin’s emissaries in America — mainly Tarak Das and Bhupen Datta (Vivekananda’s brother) — had been simultaneously trying to contact the German Crown Prince about his promise, by October 1914 they had received an invitation from Chatto to join him in Berlin. N.S. Marathe and Dhiren Sarkar (brother of Benoy Sarkar) had carried a message from the Kaiser himself for Von Bernstorff, the German Ambassador in Washington, to sanction funds to help an insurrection in India. Military Attaché Von Papen received orders to arrange for steamers on the California coast and purchase adequate arms and ammunition to be delivered to the “eastern coast” of India.

Diffident, Jatin’s associates delegated Bhupendrakumar Datta to consult Sri Aurobindo. In 1920, on returning from Pondicherry, Datta informed his Jugantar fellows that the Master thought the promise of swaraj within a year was not quite reliable; Gandhiji had come with a tremendous force and deserved collaboration but, warned Sri Aurobindo: “Do not make a fetish of non-violence and feel free to resume action as you choose.” Gandhiji himself acknowledged that trained by Jatin’s loving personality, the Jugantar militants added a special distinction to his project of Satyagraha.

Gandhiji’s repeated failures led the Jugantar men to serve him with their decision to undertake their initial project of “violence”. They would announce it in 1923 by celebrating September 9 (Jatin’s death anniversary). Datta wrote: “Bhagat Singh requested me to send him Jatindranath’s photos and some literature on Balasore. In Benares, too, we had then a powerful organisation. Thus Balasore Day was celebrated from Bengal to Punjab. Amarda (Chatterjee) issued on that very day the Swadesh, a new daily, almost all the pages full of photos and exploits of the heroes.” Two editorials in the following days intimated the readers of the Englishman about the return of the revolutionaries with their violent counter attacks.

From Bhagat Singh to Surya Sen, from Surya Sen to Subhas Bose, Bagha Jatin’s revolutionary vision of a free India swept the Indian sky like a phoenix. While in 1925 in an interview with Charles Tegart, the Commissioner of Calcutta Police, Gandhiji qualified Bagha Jatin as “a divine personality”, Tegart did not reveal to him his own thought: “If Jatin were an Englishman, the English people would have built his statue next to Nelson’s at Trafalgar Square.”

Sri Aurobindo remembered Jatindra Mukherjee as his “right-hand man” and exclaimed: “A wonderful man! He was a man who would belong to the front rank of humanity. Such beauty and strength, I have not seen. And his stature was that of a warrior.”

*

About the Author: Dr Prithwindra Mukherjee (b. 20th October 1936) is the grandson of the famous revolutionary Jatindranath Mukherjee alias Bagha Jatin. He came to Sri Aurobindo Ashram in 1948, studied and taught at Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education. He was mentioned by the Sahitya Akademi manuals and anthologies as a poet before he attained the age of twenty. He has translated the works of French authors like Albert Camus, Saint-John Perse and René Char for Bengali readers, and eminent Bengali authors into French. He shifted to Paris with a French Government Scholarship in 1966. After defending a first thesis Doctorat d’Université on Sri Aurobindo at Sorbonne, he served as a lecturer in two Paris faculties, a producer on Indian culture and music for Radio France and was also a freelance journalist for the Indian and French press. His next thesis for PhD (Doctorat d’Etat) studied the pre-Gandhian phase of India’s struggle for freedom; it was supervised by Raymond Aron in Paris University IV. In 1977 he was invited by the National Archives of India as a guest of the Historical Records Commission. He presented a paper on ‘Jatin Mukherjee and the Indo-German Conspiracy’ and his contribution on this area has been recognized by eminent educationists. A number of his papers on this subject have been translated into major Indian languages. He went to the United States of America as a Fullbright scholar and discovered scores of files covering the Indian revolutionaries in the Wilson Papers. In 1981 he joined the department of ethnomusicology attached to the CNRS-Paris (French National Centre of Scientific Research) with the project of a cognitive study of the scales of Indian music. He was also a founder-member of the French Literary Translators’ Association. In 2003 he retired as a researcher in Human and Social Sciences Department of the CNRS. A recipient of ‘Sri Aurobindo Puraskar’, in the same year he was invited by Sir Simon Rattle who was to conduct Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for the world premiere of Correspondances, opus for voice (with the divine participation of Dawn Upshaw) and orchestra, where the veteran composer Henri Dutilleux had set to music Prithwindra’s French poem “Danse cosmique” on Shiva Nataraja, followed by texts by Solzhenitsyn, Rilke and Van Gogh. In 2009 he was appointed to the rank of chevalier (Knight) of the Order of Arts and Letters by the Minister of Culture of France. Six years later the Minister of Culture appointed him Knight, too. In 2014, the French Academy recognized Prithwindra’s entire contribution by its Hirayama Award. He has penned more than seventy books in English, Bengali and French and some of his published works include Samasamayiker Chokhe Sri Aurobindo, Pondicherryer Dinguli, Bagha Jatin, Sadhak-Biplobi Jatindranath, Undying Courage, Vishwer Chokhe Rabindranath, Thât/Mélakartâ : The Fundamental Scales in Indian Music of the North and the South (foreword by Pandit Ravi Shankar), Poèmes du Bangladesh (welcomed by the literary critic of Le Figaro as the work of the “delicious Franco-Bengali poet”), Serpent de flammes, Le sâmkhya, Les écrits bengalis de Sri Aurobindo, Chants bâuls, les Fous de l’Absolu, Anthologie de la poésie bengalie. Invited by the famous French publishers Desclée de Brouwer, his biography Sri Aurobindo was launched with due tribute by Kapil Sibal, India’s ambassador in France. His PhD thesis, Les racines intellectuelles du movement d’independence de l’Inde (1893-1918) was foreworded by Jacques Attali: it ended up with Sri Aurobindo, “the last of the Prophets”. While launching Prithwindra’s biography Bagha Jatin published by National Book Trust, H. E. Pranab Mukherjee admitted: “It is an epitome of the history of our armed struggle for freedom.” To celebrate the centenary of Tagore’s Nobel award, in 2013, Prithwindra brought out a trilingual (Bengali-French-English) anthology of 108 poems by Tagore, A Shade Sharp, a Shade flat, it was launched by the President of the illustrious Sociéte des Gens de Lettres founded by Balzac. In 2020, he was honoured with the prestigious ‘Padma Shri’ by the Government of India.

Cher Docteur Mukherjee,

J’ai eu un très fort pressentiment que vous veniez de publier quelque chose ici et me voici! En fait, je le ressens depuis quelques jours mais ce matin (heure française) c’était encore plus fort. Comme je lisais le petit livre de Dinendra Kumar Roy sur les deux années passées à Baroda avec Sri Aurobindo, j’ai attendu avant de passer et malheureusement il ne me reste plus de temps pour lire votre article ce matin. Je suis un de vos admirateurs et je ressens un besoin impérieux de vous rencontrer, sachant que vous êtes à Paris et moi à Challans, en Vendée. J’ai déjà demandé à Anurag de vous transmettre mes coordonnées afin si possible de communiquer directement avec vous mais celui-ci a peut-être jugé préférable de ne pas vous déranger. Je vous réitère donc directement ma proposition. Mon adresse courriel est constituée de mon nom de famille suivi d’un point, puis de mon prénom, pour terminer avec le fameux arobas et le hotmail.com. Ce serait une grande joie pour moi d’amorcer un échange épistolaire avec vous.

It was a very captivating reading but at the same time very sad too! Bagha Jatin, a great freedom fighter and so many other extraordinarily brave men sacrificed their lives to free India. Yet, they have gone into the pages of history quite unrecognized.

A highly authentic and commendable writing about the great freedom fighter Bagha Jatin! Words fall short to appreciate the wonderful effort of Prithwindra Mukherjee ji in bringing to light the great sacrifice of Bagha jatin along with several other freedom fighters whose dedication and devotion to the motherland resulted in the freedom of this Divine land of India.

Thanks a lot Anurag Banerjee ji for publishing such enlightening words of Prithwindra Mukherjee ji!

Regards

Giti Tyagi

Editor, Creative Artist, International Author & Poetess

Book Reviewer, Translator