Dear Friends,

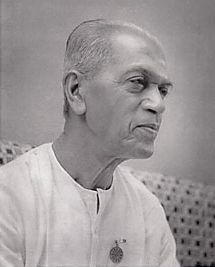

Born on 22 March 1908 as Tribhuvandas Luhar to Purushottamdas Keshavdas Luhar and Ujamben in the village of Miyanmatar (located in the district of Bharuch), Sundaram was a legendary poet of Gujarat. At the age of eighteen, his first poem ‘Ekanshe De’ was published in Sabarmati, a Gujarati magazine. After graduating from Gujarat Vidyapith he started teaching in Sonagadh-Gurukul. In 1934 he received the prestigious Ranjitram Suvarna Chandrak, a gold medal considered to be the highest literary award in Gujarati literature for his anthology of poems, Kavyamangala. He visited Pondicherry in 1940 and had the Darshan of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. He visited Pondicherry again in 1943 and two years later joined Sri Aurobindo Ashram as an inmate with his wife Mangalagauri and daughter Sudha. In 1946 he received the Mahida Paritoshik Award for his Arvachin Kavita, a critical survey of modern Gujarati poetry which went on to become a classic. In 1947 he started the publication of Dakshina, a quarterly magazine in Gujarati to spread the teachings of Sri Aurobindo in Gujarat. In 1954 he participated in the third ‘All India Writers Meet’ organized by P.E.N. in Chidambaram. In 1955 he received the Narmad Suvarna Chandrak for his anthology of poems, Yatra. His book Avalokana earned him the Delhi Sahitya Akademi Award in 1969. In 1975 he received an Honorary D. Litt from the Sardar Patel University. On16 March 1985 he received the Padmabhushan Award, the third highest Civilian Award, from the then President of India, Giani Zail Singh. In 1990 he received the Shri Narasinh Mehta Award for his contribution in the field of education and literature from the Government of Gujarat. On 13 January 1991, he left his body.

An informal introductory talk on Sundaram, the famous poet of Gujarat and an ardent disciple of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, given on 21 March 1992 to the senior students and teachers of the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education, Pondicherry, by Anuben Ambalal Purani (daughter of A. B. Purani, Sri Aurobindo’s disciple and his noted biographer) has been published in the website of Overman Foundation along with some of Sundaram’s photographs with the Mother. The English translation of Gujarati poems quoted in this article has been translated by Dhanavanti Nagda.

With warm regards,

Anurag Banerjee

Founder,

Overman Foundation.

________________

Sundaram—The Poet

Anuben Ambalal Purani

Friends, today I would like to go down my memory lane with you, to review the life of an extraordinary person who was born on 22nd March many years back.

Sundaram is a pen-name which he himself chose. It so happened that he came across the name Balasundaram, and he thought the latter part was very beautiful and he adopted it as his pen-name. I think it goes very well with his nature because he was always in search of beauty and he appreciated beauty wherever he saw it and in whichever form he saw it. He truly was searching for beauty all his life, and the name Sundaram does fit him very well. Just see these lines of his on beauty and love—

All that is beautiful on earth,

I love, I deeply love.

And all that is not beautiful on earth,

I shall beautify—

With my love,

With my deep transforming love.

Neither Sundaram’s parents nor any of his people ever dreamt of the astounding destiny which awaited the new-born child. His parents gave him a significant name—Tribhuvandas. I don’t think I need to explain the meaning of Tribhuvandas and I feel that at the end of his life, yes, Sundaram had justified, fulfilled the name Tribhuvandas. He came to the Lord and he became the slave of his Lord. And that is why I feel that that name was also a right name for Sundaram.

Young Tribhuvandas reached High School and by that time his teachers were amazed at his ability to learn, for, at that tender age he had mastered the Sanskrit language so well that he wrote short poems and even his diary in Sanskrit. He was given the title of ‘Bhasha Visharad’ by the authorities while he was still in his teens.

When Sundaram was a young man, communism had just started and it was something so new and so exciting that all the young people at that time were very much in favour of it and so their outlook on life was strongly coloured by what struck them as a new idealism.

Sundaram had begun writing poems when he was very young but very soon he rose like a constellation in the Gujarati literary horizon and all the Gujarati people hailed the new poet. He also started writing on subjects about which the previous poets never thought of writing—ordinary, insignificant events which usually made no impact on people, but Sundaram being a very sensitive person, was inspired by such insignificant events also. And at the same time, at that age, he questioned many things: such as God’s laws and why the poor suffered. Why was there injustice? Why was there inequality in society? These are the things that extremely disturbed him. And he wrote a number of poems on these subjects, creating a new character. This character was a Bhakta. Though the Bhakta loved his God, he constantly argued with Him, asked Him difficult questions. This fictitious character was called “Koya Bhagat”. Koya Bhagat went on asking his God, “Well, God, here is a woman who is suffering, who is sick and she has no medicines. What are You going to do for her?” And in that strain he wrote many poems and lastly Koya Bhagat got terribly disgusted with his God and said, “God, why don’t You go back to Vaikuntha? I think we would all be better off without You!”

This was Sundaram’s tone at that time. At the same time Gujarat was very much taken up with the Purani Brothers who had established many Akhadas (Gymnasiums) and those Akhadas had selected Saturday as a day for talks, discussions, recitations, advice whatever… they had become a kind of centre for character-building. And it seems one day Sundaram had gone to one of those Akhadas and he was asked to read a poem. In those days Sundaram was full of criticism against injustice, so naturally he recited a small poem called “Paandadi”—paandadi means a leaf. In the poem he says, “Little Paandadi was five years old and she had a brother who was just a little more than one year. So Paandadi looked after her brother—if he laughed she laughed with him, and if he wept she wiped his tears, and when he slept she put him in the cradle, and sang for him. Paandadi never realized what she was missing. She had no freedom to play, she couldn’t go to a school for study but she was happy with her brother.” And that reminds me of another poem which I have read somewhere. There the poet describes a little girl who is carrying her little brother on her arm and is going up a mountain road. It was very steep, so she was panting and a traveler who was coming down saw her and said, “He is heavy, isn’t he?” She smiled, and said, “No, he is my brother.” So in the same way Paandadi never felt that she was deprived of her liberty. She was very happy with her brother. But all days are not the same. One day her friend comes with five shinning pebbles and a game of pebbles is very attractive to a child and Paandadi didn’t know what to do. How to leave her little brother and how not to miss this glorious opportunity to play? So she tied the string of the cradle to her toes and sat down with her friend and their game started. The game was exceedingly exciting, it now reached its climax. Just then what would happen? Two wild cats came mewing and shrieking and the little girls were so frightened that they jumped and tried to run. Paandadi forgot that she was tied to a string. So the cradle was overturned, the little brother started crying loudly and just then came her mother. She picked up the child. The poet, at the end of the poem, asked, “Dear God, what kind of a creation have You made? Here is a little girl who must look after her brother. She cannot have freedom to play. Here is a little boy who needs someone to look after him. And there is that woman who must work so that she can feed her family. What a strange world You have created, God!” This was one of his very well-known poems.

The next thing in which Sundaram was seriously and sincerely involved was the freedom-struggle. At that time Gandhiji was like a magnet and all the young people were drawn to him. Sundaram also took a very active part in politics. He even went to prison for some months. And he gives expression to his feelings in one of his poems. He calls it “Rana-geet.” I think Gandhiji wouldn’t have liked that title at all—“The Song of the Battle-field.” Anyway there it was. And in the poem he says, “The Mother is in chains, Her face is washed with tears, the Mother is suffering. Who will suffer for her?” And a conch calls out to the people. Thousands of young voices ring forth, “We, we the youth will suffer for the Mother and with the Mother.” Again the conch rings out and says, “Who will go the battle-field and get wounded? Who will bleed for the Mother?” A thousand young voices echo, “We will go to the battle-field and we will bleed for our Mother.” And lastly the poet asks, “The Mother is in chains, who shall liberate her? Who shall die for her, so that she may live?” And a thousand young voices echo, “We, the sons of Mother India, we will die so that she may live.” This was the feeling Sundaram had, and I think he aroused many young hearts with this poem.

But I think not everybody is meant to lead a nation. It is not everyone’s mission to enter politics and perhaps Sundaram also was not meant for that field of life. Very soon he turned to social work. And this gentler occupation perhaps turned him inwards, and gave him time enough to look within and to feel deeply. He began to question the many ceremonies and ceremonials that the religious people do. As he had a very well-developed mind and a very sensitive heart, he questioned and at the same time he found the answer to his question. He calls that poem, “Salute Thee?”

SALUTE THEE?

Salute thee? Statue—stone?

No! No! I bow to faith’s altar-throne;

Where worshipping innocent human hearts

Find their pure adoration’s niche,

Where streams of tenderness freely flow

From God-intoxicated gazes. There I bow,

There I do bow.

Thou, inhabitant of the mind of man,

Wert made human by the human;

In this the victory of man’s manhood

I recognize and I bow.

In wood, in stone and tree, thou art in every place;

Wherever faith finds an altar, thou seated art;

I bow to thee as also to the stone.

I bow to faith’s altar-throne.

By this time Sundaram’s old ideals had all been broken. He was looking for a new ideal, a new guide. And he speaks of his despair at his unsuccessful efforts in the poem “Further over There”:

FURTHER OVER THERE

I spent a sleepless night.

An inner disquiet dogging me,

Off I went, my sack a-shoulder,

Something to discover,

Somewhere further.

I met the mundane with their hoarded treasures,

And the aged wise wayfarers. I asked them:

‘Citizens, do you know where he resides?’

‘Further over there.’

I came to the dazzling pleasure-domes.

I saw them by beauty gratified.

‘Does he stay here, my paramour?’

‘Not here, further over there.’

And there were the learned heavy with learning,

Gravely debating the undebatable.

‘Is this the abode of God, O revered ones?’

‘No. Further over there, further.’

A glimmer of lamps, a tinkle of temple bells,

The worshipping, prostrate devotee.

Once again, in hope, I posed my riddle:

‘Is this where he lives, my paramour?’

‘No. Further over there, further.’

Not with people, not in pleasure;

Not in learning, not in temples.

Everyone answers: ‘Further, further.’

Where further?

This poem reminds me of ‘The Hound of Heaven’ by Francis Thompson. That poem is in complete contrast to Sundaram’s. In ‘The Hound of Heaven’ the poet describes his desperate efforts at fleeing from the pursuing Hound—but is there anyone on earth who can escape the Hound of Heaven (The Divine’s Grace)? Finally the poet is seized by the Hound and he hears a soft murmur “who would love thee save me?”

After the futility of his search Sundaram was in great despair. These periods of depression which some call ‘the Valley of the Shadow of Death’ are common to all extraordinary people. There are some who come out of it and many who succumb to it. Sundaram was lucky enough to feel a ray of Light in the depths of despair and come out with a new life. He describes this experience in a dramatic and colourful poem called ‘The Story of a Nobody’.

THE STORY OF A NOBODY

(1)

I am nothing.

Such a nothing.

No one’s ever whispered to me: ‘Welcome.’

Such a nothing I am.

What should I do?

Where do I proceed?

In this soulless world I roam;

Aimless, anchorless, vagabond.

Look! These festive meetings,

Consultations, greetings,

Happy, candid, casual chats

Where hearts quiver open and bloom.

I too would go there, be a part.

I go, I stand, I wait.

No one’s bothered that I live, I breathe.

I am such a lifeless, shadowy nought,

Would someone tell me ‘Begone!’

They wouldn’t tell me ‘YES’ I know,

But I am such a nothing

They didn’t even give me a ‘No!’

(2)

And so I thought

This life of mine a running waste

Why perpetuate?

I went to the cemetery.

I dug myself my own burial pit.

Not for me the luxury

Of a ceremonial interment.

I called the Lord, stepped in, lay down.

To pull the earth-shroud over my face

I stretched my arms, looked up:

The skies met my eyes;

My fingers for that instant froze.

Oh! that pregnant midnight moment,

Awesome, eternal!

Flinging aside my depression’s heavy cloak,

Life stood there and stared,

Deep into my ocean-eyes,

For the very first time!

Her body was the milky way

And her fairy fragrance

Floated gently in the breeze.

Then from her snow-white robe

Like a love-drop of nectar

Broke out a star; softly first

And whizzing like an arrow next.

Her cheek wore the rose of happy hearts.

What happened then,

I just do not know.

(3)

I opened my eyes,

Everywhere there was light,

Tender, twinkling, pure,

White like the champa flower.

And then I noticed

On my tomb’s edge,

That lucid light in person stood.

She saw my open eyes and, happy, said:

‘A nothing, eh?

Good you came here and rested so, my love!

Here now will in my sowings throw

And on this living earth shall grow

My dream-flowers,

My very own-dream flowers!’

Then she smiled a smile,

So soothing, so fresh, so warm,

I simply shut my eyes.

(4)

I woke up to the glare of a naked noon.

There was no burial pit nor ground.

In the embalmed cosy lap of a tree

I lay reclined. Thrilled my limbs

With the mad murmur of spring.

I gazed at the universe reborn.

Wherever I looked

A garden was in bloom.

In its subtle, myriad-shades

Flowed the wonder-warmth of my gaze,

The rich champaka raga of my new life.

So far, Sundaram’s life was a lonely journey. With this new awareness, with this new Light within, he at last found a companion, a companion whom everyone searches for and some are lucky to find. He at last was ready for love, for true and deep human love. For, that love demands a certain preparation, a certain growth. Not all human beings are capable of giving or receiving it, and some never even taste the depths of true human love. He describes an event which took place one evening with his beloved. His language shows us the ardour of an intoxicated lover. He calls the poem “That Lovely Evening.”

That Lovely Evening

On that lovely evening,

With lovelier, luscious limbs,

You were standing,

Your graceful body resting

At the doorway, creeperlike.

To feel? to touch? to kiss?

My being wavered. My heart would not consent,

This superb, sculptured charm,

For an embrace was meant.

In her beauty’s golden lure, it froze.

I resolved to retreat.

I stepped back and beheld:

From her garment’s guarded pleat

Shot out an arm, Cupid’s arrow.

And her body, arched like a stringed bow,

She thundered: ‘You cannot go!’

I could not make a move.

Neither this way nor that,

Nearer nor farther.

On a dumbfounded rock

Standing single in the silenced seas

My ship had shattered.

Life a life-saving boat,

Towards a wreck

You glided towards me.

To feel? to touch? to hold?

You did not, puzzled, pause,

O purity!

On that lovely night,

You, a lovelier sight.

Thus love came in a blaze of beauty to Sundaram. We can see that there was an unseen hand guiding his destiny. And it wouldn’t allow him to rest with this surface experience of love. He had to understand that when you truly love, love and adoration become the same thing. His love deepened and he forgot the distinction between love and adoration. And he found divinity in the person he loved and it was almost an occult experience through which he passed. He describes it in his poem ‘I Saw Thee’ and finally tells us that it truly was an occult experience.

I SAW THEE

From that far,

From so near,

I have seen you.

Someone’s lovely at a distance,

Someone’s comely when close by.

But near or far,

Charming you are,

For ever unchanged,

Ever comely, ever lovely, enchantress.

I was wondering:

How did it happen—

This fragment from heaven

Fallen to earth?

Questioning, I shut my eyes.

A curtain opened to reveal

The universal chakra, the ever-rotating wheel,

Whose bars were golden shafts of light,

The rim a brilliant rainbow.

And at the centre-hub

A statuesque beauty sweet

Shone upon her lotus seat.

The soft sparks of the clustered stars

Gathered in her hands, raised rose-red

As if in blessings.

Her intent gaze seemed to say:

‘I have known you for centuries.

I am awaiting you ever since.’

I implored her:

‘Bestow on this impoverished earth

A beauty, that everyone, from everywhere,

In every way could always receive.

From your compassion’s cascade,

May no one ever go unslaked.’

Her luminous lips shone more

In an answering smile;

Then from that circling wheel

She snatched a shaft and shot at me

Her blade of beauty.

Her lips still alit with the same sweetness.

I sank into a soothing slumber.

Where did she strike,

I do not remember.

When my eyes awoke,

I saw you there on earth,

The self-same beauty, that very charm;

The symbol of my prayers

Perfected, personified.

I look at you again and again,

From far and near,

With open eyes or shut,

You are present,

Always, everywhere.

O beauty incarnate,

There is none your like down here.

This story, occult—eh?

Why did I recount it to-day?

Sundaram’s destiny did not rest with his adored love. He had to learn to outgrow his individuality and all his ideals, his love had to grow vaster, it had to include the whole of the universe. When he had that experience he wrote it in a short poem entitled ‘My Blossoms’.

MY BLOSSOMS

When my buds bloomed,

My heart with their pollen was so imbued,

The melodies of earth, all waned to nought.

When my love opened

My being so awakened

That its intense glow

Dimmed the firmament fires.

But all my flowers faded, and my love,

They shrank, dried and drooped.

So too swooned my life crying, alas!

Came evening.

The twilight tune tiptoed to midnight.

My eyelids opened. I absorbed

The magnanimous blue-black of the dark.

And I found my flowers, twinkling in the stars.

And I witnessed my love, delight in every heart.

With this widening Sundaram was ready to meet his master. It is around this time that he came to Sri Aurobindo Ashram. When I first saw him he gave me the impression of someone who was very refined and cultured. He went back to Gujarat. But the lure of this place, the attraction of the Mother and Sri Aurobindo had to bring him back here. He saw Sri Aurobindo for the first time, and wrote a poem on Him. This, his first poem on seeing Sri Aurobindo, is a proclamation of Sri Aurobindo’s divinity. He describes Sri Aurobindo as a second Vaamana, who conquered many worlds with one step and brought back things about which humanity has been only dreaming and hoping—‘SRI AUROBINDO’.

SRI AUROBINDO

O thou, who having crossed all human shores

Hast in a single step conquered the seven nether worlds

And in another all the higher spheres,

Dwellest here on earth, a calm immeasurable soul.

There, whence return man’s body, brain and heart

Defeated, lost, thou hast founded thy haven;

And upon this earth, godlike, seekest to create

The transcendental’s chain of divine dwellings

Where thy superconscience would glow in ecstasy.

The unbridled bulk of world-destroying energies

Thou holdest, like a flower between thy fingers;

While in the cupped hollow of thy hands smoothly sway

The unfathomed ocean-whirls of stupendous light.

As melt and flow the frozen mountain peaks

Thy inexhaustible divine compassion friendly flows

Into waters the world never tasted before.

O thou, magnanimous flaming fire,

Blissful, brilliant, benevolent,

What oblations could quench the intensity

Of thy infinite sacrificial flames?

After some time, Sundaram became an inmate of the Ashram. In the Ashram each person has to try and bring out his inner experience into his outer life. Sundaram too tried this in his own way. He brought out a Gujarati Quarterly magazine which he called ‘Dakshina’. And in that magazine he was the first to start certain new columns, like giving the readers the important news regarding the Ashram and encouraging his young students to write good prose and poems in Gujarati which he published in ‘Dakshina’.

Very soon, Sundaram translated the Mother’s little booklet ‘The Ideal Child’ into Gujarati and published in as ‘Adarsh Balak’. Almost immediately Purani and Sundaram took up the big work—naturally with the Mother’s Blessings—of reaching ‘Adarsh Balak’ to every child in Gujarat. And both of them went to Gujarat, and with the help of devotees there, organized a ‘Shibir’, a spiritual camp. Thus began a chain of Shibirs, at different places in Gujarat—and elsewhere too—where the devotees gathered together for a few days around Purani and Sundaram and tried to concentrate on the Mother and Sri Aurobindo during this entire period.

In one such Shibir, at Ganganath—(the temple which, on the bank of our sacred river Narmada, Sri Aurobindo had visited) a few devotees requested Sundaram to ask the Mother’s permission to start in Gujarat a new city similar to Auroville near Pondicherry. In spite of all the difficulties involved in this venture, Sundaram was not at all discouraged. He asked the Mother’s permission and She graciously gave it, and also gave the new city a name: ‘Ompuri’. It took him a couple of years to get the land and to collect the money for it. Finally he was able to lay the foundation stone of the new city of ‘Ompuri’.

By that time he could feel that his health was failing. So he decided to make a board of trustees and he handed over the responsibility of the new city to the board.

Last year [1992] Sundaram passed away. I went to see him for the last time. And I was satisfied to see his face because his face reflected all that he must have acquired in his inner life. There was great peace and calm, and a detachment. It was so great that somehow I was reminded of the Buddha.

Thus ended an adventurous and beautiful life, somewhat like the Christmas tree which shines and glimmers with many gifts.

I would like to evaluate Sundaram’s great output in literature before closing our talk today. He translated certain plays from Sanskrit, he translated some books from German into Gujarati and of course many works of the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. Besides that he wrote many short stories. Once, when I met him, I asked him, “Why don’t you write short stories now?” He said, “You know, to write those stories I have to go down and I don’t feel like going down.” Yes, truly those stories were very much the play of the vital, the colour of the vital. And, further, he has written a great volume on criticism. He calls it ‘Arvaachin Kavitaa’. Before he wrote this volume he read about 800 books and now it is considered a milestone in Gujarati literature. And I think that book was the expression of his brilliant analytical mind and his clarity of thinking and expression. Lastly, you have read, you have heard his poems which were truly the expression of his aspirations, of his intense experiences.

Looking back on that life, I remember a Gujarati poet. His name is Dhiro. He wrote a muktak, i.e., a two-line poem. In it, Dhiro says: “Taranaa othe dungar re, dungar koi dekhe nahi”. Which means—“There is a huge mountain behind a blade of grass but nobody can see the mountain.” It’s the same with us.

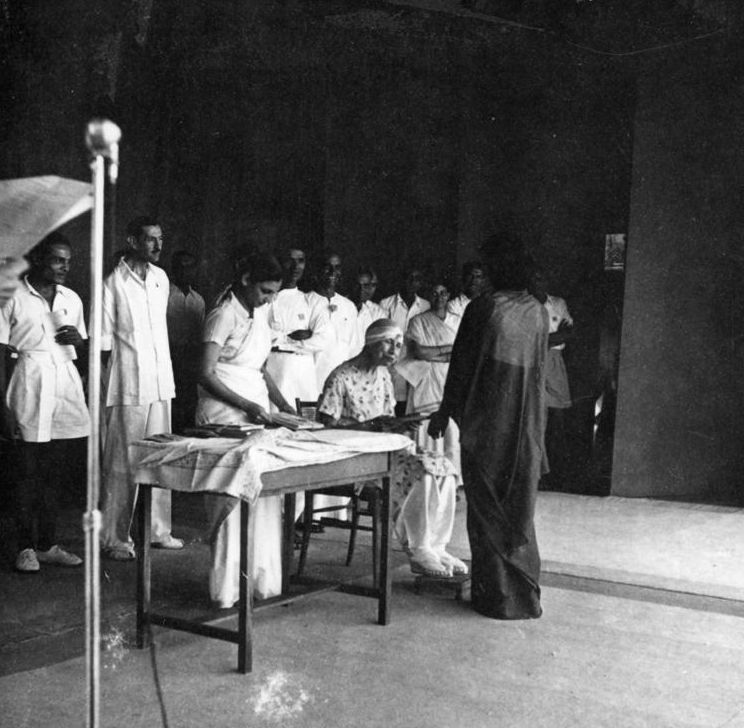

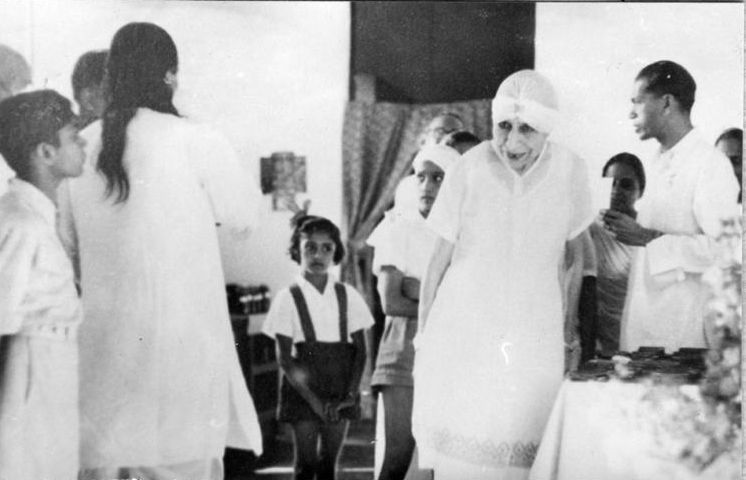

The Mother distributing school prizes on the stage (circa 1950). Also seen with the Mother: Shanti Doshi, Krishnakumari, Sailen, Sujata Nahar, Sundaram and Krishnalal Bhatt.

Same as above. Also seen with the Mother: Chimanbhai Patel, Norman Dowsett, Sujata Nahar, Shanti Doshi, Sailen, Krishnakumari, Sundaram and Krishnalal Bhatt.

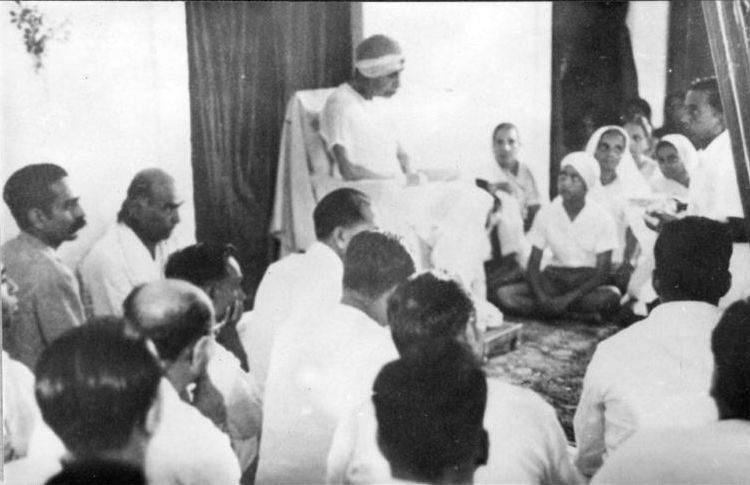

Sundaram with the Mother on 22 February 1957

The Mother with Sundaram, Pujalal, Kesarimal and Kirti on 22 February 1958

The Mother with Sundaram and Kirti on 22 February 1958

The Mother with A. B. Purani and Sundaram

Photographs courtesy: Ms. Tara Jauhar.

ONE OF THE BEST WRITE-UPS, ANURAG

Sudhaben, Sundaram’s daughter. took a lot of fotographs of the Mother’s terrace darshans, from 64-73 which are on the site saa.online, and also many of the AV inauguration, most people might not be aware, Mother selected a particular foto for publication and gave significance to it, one in library hall , cape flying..ask her..lot of stories of father and her life here..you can get much from her interview with Narad..

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qhVWYbnJCs&t=20s part-1 and 2nd part also there 45 mins each, a must see and hear to know about Sundarambhai , great man, yogi, poet laureate…complete works runs into more than 10 vols…

Well done , Anurag . Excellent work in the service of The Mother .