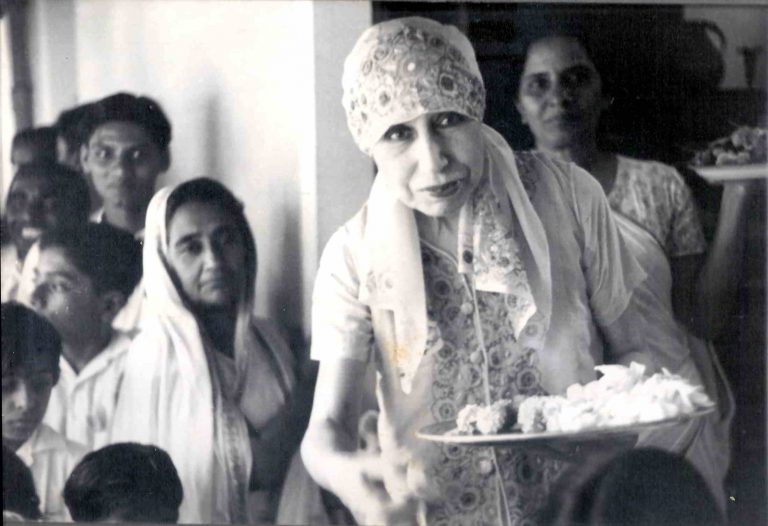

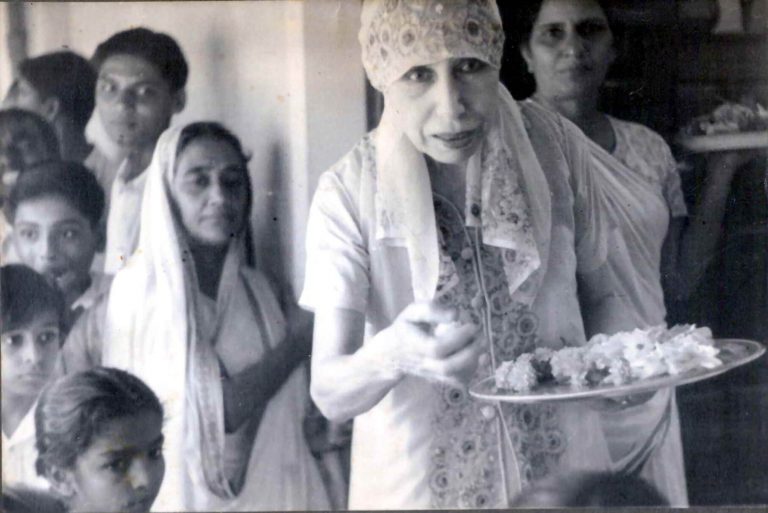

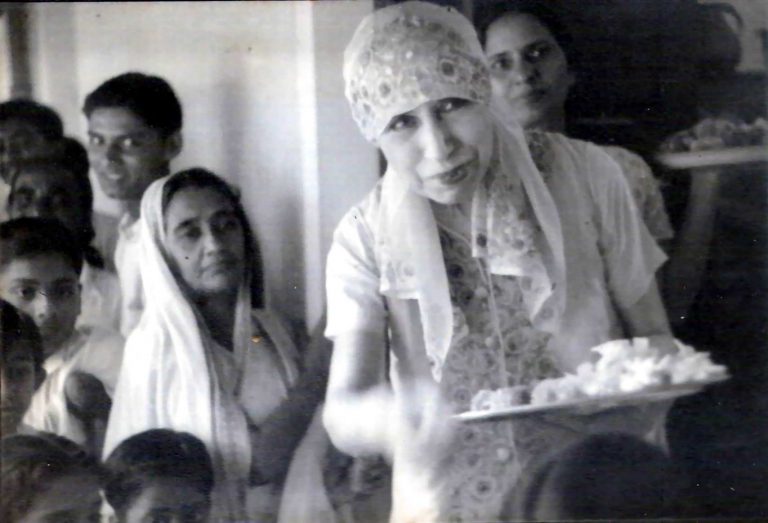

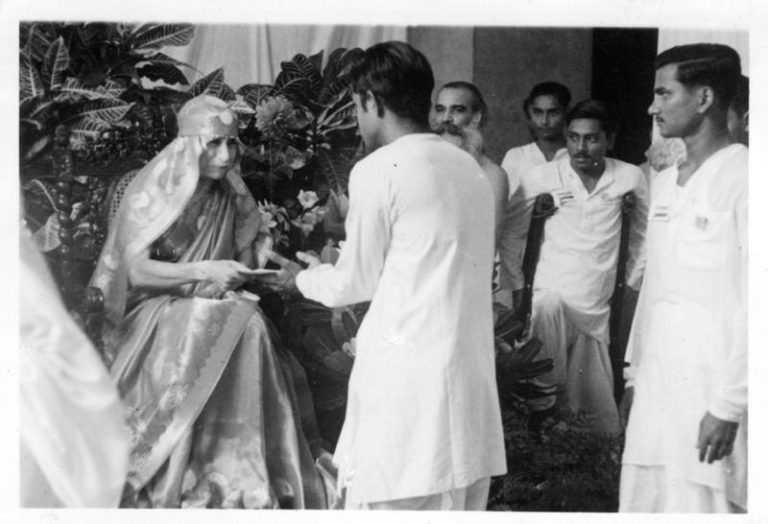

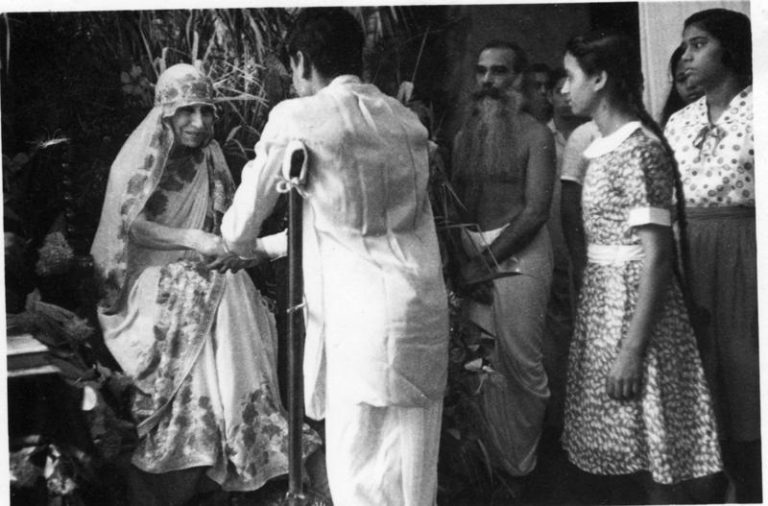

The Mother with Dr. Prithwindra Mukherjee

The Mother with Dr. Prithwindra Mukherjee

On the internet wall of SAICE, along with the good news of my Padma award, announced on 25 January 2020, you have come across a photo showing me on crutches, standing with my parents and my brothers. A well-wisher has even posted it with a rare gusto on the Messenger page. This photo is associated with so many phases of memory that I would like to share with you some of those impressions, leaving you to judge how far it is worth reproducing for posterity.

You who have seen in recent times the tragic results of a gnawing — Corona-virus, may have also been shocked probably by the sight of this photo showing the damage that could cause another virus — Polio — on the limbs of a little boy bubbling with love for life. It all happened in the early years of 1940s, during the World War II when most of the competent doctors had been mobilized. Vaccine for Polio was yet to be invented with monkeys from India serving as guinea-pigs. My parents, young as they were, did not give up hope of recovering my affected freedom: allopathic, homoeopathic, unani, ayurveda… nothing brought them the expected relief.

I was surrounded with affection. I had a steady supply of adequate reading. I had at my disposal my mother’s harmonium which had been fabricated by Kunjalâl Sâhâ, one of the childhood friends and revolutionary colleagues of my grandfather. Kunja-dadu had been arrested in 1908 at the Maniktola garden. On the occasion of my parents’ marriage in 1930, he had imported special reeds from Germany for preparing this gift. A spontaneous feeling of gratitude towards my parents and relatives helped me express myself in verses. Whereas my Pishima’s husband Lalitkumar Raychaudhuri — a pious and aristocratic man — taught me Sanskrit hymns, my maternal uncle, Prabodhkumar Chatterjee, a double gold-medalist in physics from the University of Calcutta, looked after my general education.

In 1948, admitted as students of the Ashram school at Pondicherry, we three brothers — Rothin, myself and Togo — were warmly welcomed by the Mother. On seeing her coming out of the Ashram tennis court, I had a vision of golden lilies blossoming under her beautiful feet. ”An arid heart Thou canst not bear,” was the line from Anilbaran’s song dedicated to Lakshmi — Mother of all harmony — came to my mind. I wanted her to indwell my heart with all that sweetness.

At the same time, a sense of misfit haunted me in secret. How could I forget that I was not like the other children ? A kind of escapist attitude flung me to find refuge in the sea: while bathing, with a batch of dare devil comrades we caught hold of fishermen’s catamarans, paddled up to a good distance, before swimming back to the shore. Adept of parallel bars and roman rings, I discovered the thrill of swinging with the rings up to almost 90° forward and proportionately backward: a sensation of visiting heaven invaded me, reminding me of Baudelaire’s invitation to Ascent. Or else his despair at the sight of the Albatross, princely as long as it flies, but becomes awkward once it lands. Having had the privilege of a teacher like Sunil-dâ for botanic, we had an additional satisfaction of getting inspired by his passion for astronomy. It was so comforting to see him with smiling eyes, dressed as a Bengali Babu and listen to his impeccable speech in French. Night after night, having spent on our bare terrace sleepless hours observing the trajectory of the constellations, I used to enter a field of sleep where impressions of all kind gathered jumbling. Shortly after, I was to compose poems like “They call me in dream/ Those star-like souls/ And sweep over my mood/ As the wave-crest rolls”, poems which Amal Kiran (Sethna) was to publish in Mother India with a sincere pleasure.

In the name of individual liberty which the Mother cherished so much as a key-word in her pedagogy, I was free to frequent solitary reapers as long as it was a help for my spiritual progress. But escapism being far from the spirit that the Mother and Sri Aurobindo chose to cultivate, I received a timely warning that I belonged to a collective experiment and it would be worth tuning my piccolo with the other instruments. Compassionate as she was, the Mother showed a kin interest in my personal worry. Drawn by her proximity, I was allowed to stand near the wall close to her and watch her distributing flowers to disciples at the Meditation Hall. During the “Vegetable Darshan” I stood just one step below the doorway so that when the Mother came down the staircase, her left elbow touched my forehead; at times I received her cool presence on my right cheek, while she gave me a smile of accepting the play. But on occasions when I felt my body was uncomely to be seen beside her, I disappeared. Such was the case when Henri Cartier-Bresson came to snapshot the Mother and Sri Aurobindo : at “Vegetable Darshan”, for instance, I left my wonted spot on the Mother’s left and went to hide myself behind Sarala Ganguli, by the side of Gangaram and Krishnakumar.

The Mother wanted to strike her hammer at the very root of the evil. In her wish to sensitize the muscles that had been declared as paralyzed, with the complicity of Dada (Pranabkumar, head of the department of physical education), the Mother examined them one after the other, before asking him to prepare a chart for active and passive physiotherapy, including massage and sea-bathing. As and when any response came from one of the inert muscles, the Mother — full of joy — considered it to be the victory of Consciousness. This manner of applying an active will power to activate cells considered to be dead has gained the large world of experimental osteopathy and physiotherapy. Surprised by the doing of one professional practitioner in the Val d’Oise area, I heard him admit: “This method has been taught by the Mother of Pondicherry!”

Every morning the Mother went on giving me a bunch of calendula to keep ablaze her wish and order: “Persevere!”

Partially absent from some of my favorite classes owing to my therapy, I stood, however, second at the year-end. “What if I could attend all the periods regularly ?” arose the disturbing question. I liked music, history, philosophy, literature, I liked toying with four European and six Indian languages. Slowly I shunned my therapy. Dada was looked for in connection with his department, where I worked as a part-time librarian.

When, in 1966, I was about to come to Paris with a scholarship from the French Government to write a thesis at the coveted university of Sorbonne, congratulating me for the information, the Mother reminded me all the same that French surgery was very far ahead of its times. Though on the spot such an insistent suggestion offended my self-love, somehow or other, step by step, the Mother’s occult control over circumstances grew so obvious that on reaching Paris, like the poet of the “Hound of Heaven”, I had but to surrender. I had to admit that an invisible red carpet was leading me to accept as her gift a proposal from the internationally recognized French surgeon, Professeur Merle d’Aubigné : he was eager to rid me of my crutches with a series of operations. Though painful, they were compulsory, if I did not want to suffer further sequel with the deterioration of my shoulder muscles.

Advised by the Mother, Satyavrata-da wrote to the surgeon accepting the latter’s proposal. Accompanying the Mother’s letters — often registered as air-mail — Pavitra-da always added a note to encourage me. Gambelon as a service to the Mother went to the post office to bring them, with a pseudo-jealous grunt: “It seems the Mother does not write any more!” Having corresponded with Sri Aurobindo since the 1930s, Gambelon was a genuine sadhak. Other letters from Dada, Nolini-da, Amrita-da, Sunil-da, Sisir Mitra, Rishabhchand, Françoise (Purna) and many other inmates of the Ashram flooded me with joy. My parents and my brothers kept me informed about the reactions of well-wisher inmates of the Ashram.

In the middle of the morning of 19 June 1967, while on a stretcher I was approaching the operation theatre at Hôpital Cochin, Gambelon came running with the Mother’s telegram. Placing it on my heart, I handed it over to Gambelon before getting anaesthetized for more than sixteen hours.

I spent two months at the hospital and four months at a nursing home specialized in post-operatory muscular rehabilitation. Once again, discharged from the nursing home, had I not listened to my old daemon goading me in favor of neglecting sessions of physiotherapy, I could freely move about with a walking stick, as demonstrated by the surgeon. Instead, I depended on a pair of light aluminum crutches. Eagerly waiting for my home coming like a conqueror, the Mother did not conceal her disappointment on seeing me appear with this partial prize.

This mobility allowed me, however, to trot over four continents of the globe between 1967 and 2003: at times as a Fulbright scholar covering US archives from coast to coast; or leading a CNRS mission for shooting documentary films in ethnomusicology; or else accompanying as artistic director a team of Radio-VPRO from Holland to record the Jayadev festival of the Bauls of Bengal. Along with my official retreat in 2003, came the wearing out of my tendons and muscles of the shoulders, resulting in discovering the world from a wheel chair.

__________

About the Author: Born on 20th October 1936 to Tejendranath and Usha Mukherjee, Dr. Prithwindra Mukherjee is the grandson of the famous revolutionary Jatindranath Mukherjee alias Bagha Jatin. He came to Sri Aurobindo Ashram in 1948, studied and taught at Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education. He was mentioned by the Sahitya Akademi manuals and anthologies as a poet before he attained the age of twenty. He has translated the works of French authors like Albert Camus, Saint-John Perse and René Char for Bengali readers, and eminent Bengali authors into French. He shifted to Paris with a French Government Scholarship in 1966. He defended a thesis on Sri Aurobindo at Sorbonne. He served as a lecturer in two Paris faculties, a producer on Indian culture and music for Radio France and was also a freelance journalist for the Indian and French press. His thesis for PhD which studied the pre-Gandhian phase of India’s struggle for freedom was supervised by Raymond Aron in Paris University. In 1977 he was invited by the National Archives of India as a guest of the Historical Records Commission. He presented a paper on ‘Jatindranath Mukherjee and the Indo-German Conspiracy’ and his contribution on this area has been recognized by eminent educationists. A number of his papers on this subject have been translated into major Indian languages. He went to the United States of America as a Fullbright scholar and discovered scores of files covering the Indian revolutionaries in the Wilson Papers. In 1981 he joined the French National Centre of Scientific Research. He was also a founder-member of the French Literary Translators’ Association. In 2003 he retired as a researcher in Human and Social Sciences Department of French National Centre of Scientific Research in Paris. A recipient of ‘Sri Aurobindo Puraskar’, in the same year he was invited by Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for the world premiere of Correspondances, opus for voice and orchestra where the veteran composer Henri Dutilleux had set to music Prithwindra’s French poem on Shiva Nataraja, followed by texts by Solzhenitsyn, Rilke and Van Gogh. In 2009 he was appointed to the rank of chevalier (Knight) of the Order of Arts and Letters by the Minister of Culture of France. In June 2014, he received from the French Academy (Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres) the 2014 Hirayama Award for his long career as an author, especially for his French Thesis on the pre-Gandhian phase (1893-1918) of India’s freedom movement. On 1st January 2015, the Prime Minister of France appointed him Chevalier in the Ordre des Palmes Academques. In 2020 he was honored with the ‘Padma Shri’ by the Government of India. His published works include titles like Samasamayiker Chokhe Sri Aurobindo, Pondicherryer Dinguli, Bagha Jatin, Sadhak-Biplobi Jatindranath, Undying Courage, Vishwer Chokhe Rabindranath, Thât/Mélakartâ : The Fundamental Scales in Indian Music of the North and the South (foreword by Pandit Ravi Shankar), Poèmes du Bangladesh, Serpent de flammes, Le sâmkhya, Les écrits bengalis de Sri Aurobindo, Chants bâuls, les Fous de l’Absolu, Anthologie de la poésie bengalie, In Quest of the Cosmic Soul and Les racines intellectuelles du movement d’independence de l’Inde (1893-1918) ending up with Sri Aurobindo, “the last of the Prophets”.

A most touching testimony revealing the Mother’s infinite love and concern showered on Her child who has made Her proud with his extraordinary achievements in spite of all the physical pain and hardships.

Merci, Prithwin-da, for sharing this with us!

” When to the sessions of sweet silent thought , I summon up remembrances of things past “- so sang William Shakespeare and so touchingly and candidly now ” Prithwin- da ” has recalled the sweet and sour memories of the past and ever present – the Divne Mother’s Love and Grace during his years of struggle and overcoming the handicap inwardly / outwardly so to speak –

Merci ! Prithwin – da for this –

Surendra s chouhan SAICE ’69

পরম শ্রদ্ধাস্পদেষু

মেজদা,পুরো লেখাটা পড়লাম । তোমার অসামান্য এই জীবন শ্রীমায়ের আশীর্বাদ ধন্য আর অসংখ্য মহৎ মানুষের সাহচর্য তোমায় এক উদ্জ্বলতম জ্যোতির্বলয়ে পৌঁছে দিয়েছে, এইসবের সামান্য টুকুই জানা ছিল । তোমার জীবনের প্রবল প্রতিকূলতা সত্ত্বেও তোমার সংগ্রাম তোমার ধী শক্তি আর অসীম ইচ্ছাশক্তি আর সর্বোপরি শ্রী মায়ের আশীর্বাদ আজ তোমায় এক উচ্চতম স্থানে প্রতিষ্ঠিত করেছে । সত্যি বলতে কী তোমার এই দিব্য জীবন সেভাবে জানা ছিল না , টুকরো টুকরো কিছু হয়তো জানতাম । আজ মনটা ভরে গেল ,অনুভব করলাম মানুষ ঈশ্বরের কৃপা থাকলে আর নিজস্ব ইচ্ছাশক্তির জোরে শিখর স্পর্শ করতে পারে ,তুমি তার জ্বলন্ত উদাহরণ ।

আমার ভক্তিপূর্ণ প্রনাম জানাই ।

তোমার স্নেহের রাণা

Thanks for the lovely article describing the Mother´s miracle and the beautiful and rare photographs of the Mother and Prithwin-da, Gangaram-da and others. I fondly remember Prithwin-da as my Bengali teacher in the Ashram.

So good to learn about the recent GOI Padma Shri award given to Prithwin-da!

Arindam

Sweden

Prithwin-da’s narration is poetic and flows like a river destined for the ocean. The Mother’s references, intertwined with his life and well-being, are refreshing – it did give me the experience of witnessing her, transcending space and time.

A concrete example of the Mother’s supreme grace. I am fortunate enough to be Prithwin’s friend from a distance. I was impressed by his many achievements and congratulate him. I have learned that quite often what is perceived as an unfortunate circumstance turns out to be a really great manifestation of Divine Grace. Prithwin is a prime example. May the Divine bless him as always.

Congratulationa Prithwida for your great achievement and receiving Padmashree award fromGOI.I was also student SAICE and was close to your father lt.Tejenjyatha.My aunt lt.Bela Ghosh ofEmb.dept .was an ashramite since1944.I still cherish my Ashram days,Divine Mother’s darshan,proximity with Manada,Pranabda,Gangaramda and others. Presently I am professor head of psychiatry dept calcutta national medical college.I prey for your good health and more academics from your end.